Robots may be the stuff of science fiction novels and movies for some. But to BYU electrical and computer engineering Professor Randy Beard, they’re an exciting reality.

“(Robots have) so many, many useful applications,” Beard said. “We work on really fun and innovative problems, and we get to do things that you can see work.”

Beard is a director of BYU’s Multiple Agent Intelligent Coordination and Control Lab, also known as the MAGICC Lab. Established in 1999, its primary goal is developing a robot that directs itself.

“What we’re trying to do is … make robotics systems more intelligent and more autonomous and more usable,” Beard said. “We’re writing computer algorithms that … fly robots.”

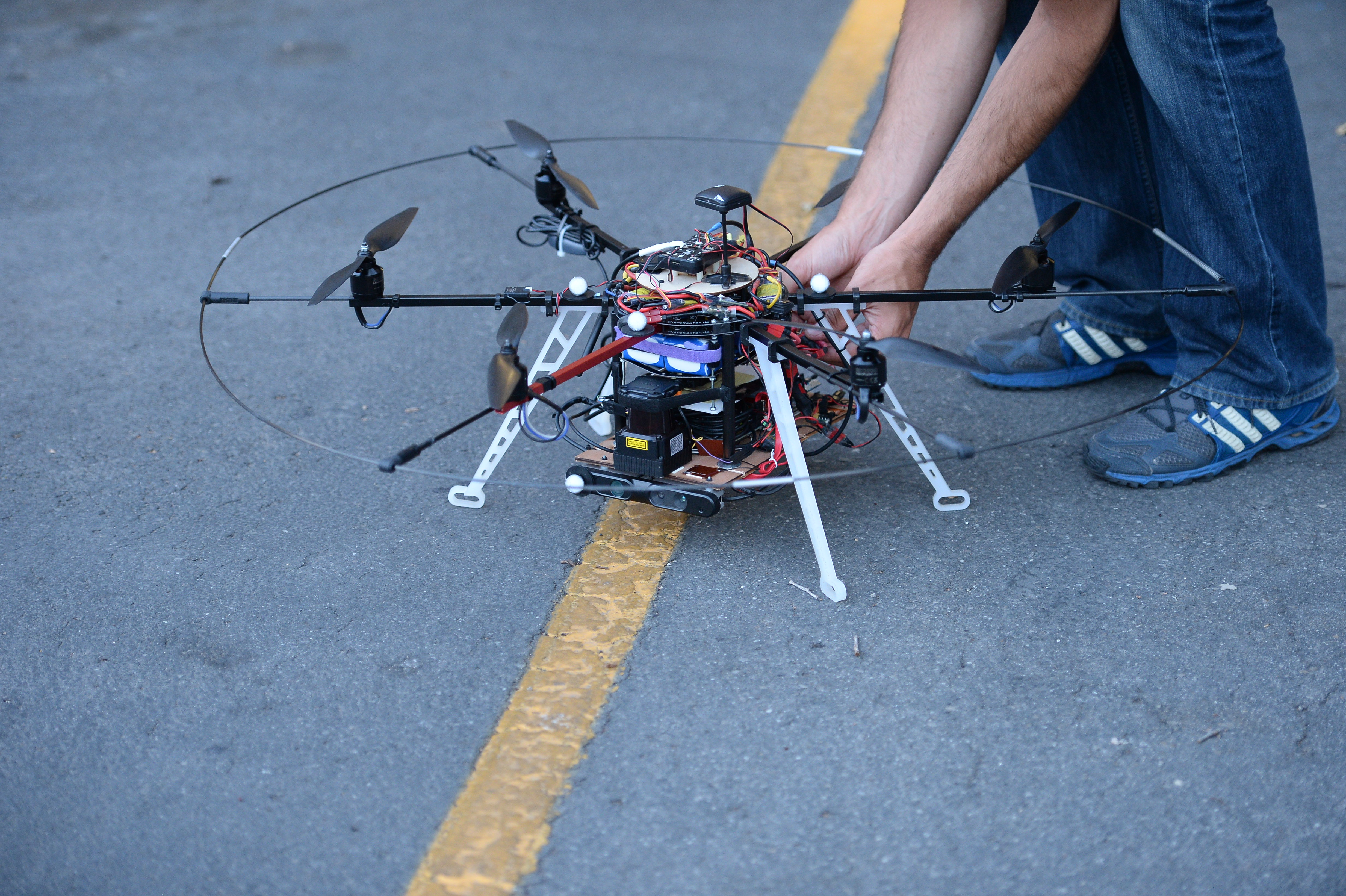

Those flying robots are unmanned aerial vehicles, more commonly known as drones, and the main research focus of the MAGICC Lab. The lab focuses on small aircrafts with a wide variety of uses. All flight tests are approved through BYU Risk Management.

“We work in the area where we’re looking at small vehicles, things that can be hand launched … but have autonomy,” Beard said. “You have civil applications like law enforcement and border control … things like wildfire surveillance … pipelines and power-line surveillance. All of that can be automated with unmanned air vehicles.”

In addition to the MAGICC Lab, Beard works with the Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems, a coalition of five universities and 23 companies that develop drones, according to center’s operations manager Rose Allen. The center and MAGICC Lab sometimes work together, but they’re also distinct organizations with separate projects.

Tim McLain is another director of the MAGICC Lab and the director of the Center for Unmanned Aircraft Systems. McLain, a mechanical engineer and BYU professor, worked on underwater vehicles while completing his doctorate degree, which influenced his understanding of drones.

“Interestingly, some of the fundamental dynamics or governing behaviors … that govern how these vehicles work (have) similarities between underwater vehicles and aircraft, and ground vehicles too,” he said.

McLain said drones have historically been fixed wing aircraft developed by the military, but now some companies are looking at them for commercial and communication applications.

“Parcel delivery is something that’s being looked at very intently by Amazon, Wal-Mart, DHL and other people,” McLain said. “Facebook is looking at having high altitude (drones) that would be solar powered and stay up for long periods of time, and they would be used to pipe high-speed internet to parts of the world that don’t have the infrastructure … for internet.”

Drones have the potential to change the aircraft industry in the long term, but not before other technologies develop, according to McLain.

“I think the way that will evolve is we’ll see self-driving cars come along first,” McLain said. “Once we’re convinced of the safety of that … then I think you’ll see large unmanned aircraft used for parcel delivery … and then finally passenger aircraft.”

McLain said although he doesn’t consider drones safer than planes flown by people, quite a bit of passenger flight is already automated, with the pilot simply overseeing processes like takeoff, landing and navigation.

“(The pilot) is just watching to make sure nothing bad happens,” McLain said. “(But) even under challenging conditions, the automated landing systems can do a better job than the pilots can, so in that sense, the automation that we have currently is better and safer than what a pilot can do.”

Both Beard and McLain said no one should be afraid of drones invading their privacy.

“You’re probably much more likely to have an invasion of privacy from someone putting a webcam on your fence than trying to fly a drone around,” Beard said. “Drones are very loud and they don’t fly a long time, so I think that privacy concerns are overblown.”

McLain said he agrees new legislation is not necessarily needed because existing laws already protect people.

“I think unmanned aircraft are a technology just like … the internet,” McLain said. “We would all be pretty sad if the internet were taken away because it was viewed as a potential harm. … There will be a lot of good stuff that comes from unmanned aircraft.”

Some of that “good stuff” is already being developed by doctorate electrical engineering student David Wheeler, who has worked four years in the MAGICC Lab. His research involves teaching multi-rotors to fly when GPS is unavailable.

Past MAGICC Lab projects include a “Tailsitter” that lands vertically and an airplane that’s able to calculate the locations of targets on the ground while flying. A team of undergraduate students is currently preparing to compete in the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems-Student Unmanned Aerial Systems competition.

To Wheeler, the future is drones.

“I think over … the next thirty, fifty years … they’ll be interacting with us regularly to help us and shape the way we live our lives,” Wheeler said.

McLain shared Wheeler’s optimism.

“(It’s great) to work with young people that are so capable,” McLain said. “The best part is just seeing something new work for the first time, coming up with an idea that has the potential to provide a useful capability to an end user, something that’s marketable and valuable to people. I think the capabilities that will develop will enhance people’s lives and ultimately save lives too.”