Disney, Warner Bros. Entertainment, 20th Century Fox and Lucasfilm are suing the Provo-based filtering and streaming service, VidAngel.

“So far, they’ve been very persuasive and the district court has sided with studios,” said VidAngel CEO and Co-founder Neal Harmon. “We have appealed their ruling and intend to appeal it to the Supreme Court if necessary.”

Harmon said the Family Movie Act of 2005 enables the legal filtering of programs as long as the filtering is done on an authorized copy, watched privately in a home setting and not made into a permanent copy.

Although the act was written when DVDs were the primary method of movie distribution, Harmon said he believes it applies to modern streaming technology as well. Harmon also said VidAngel’s current business model meets all three Family Movie Act requirements.

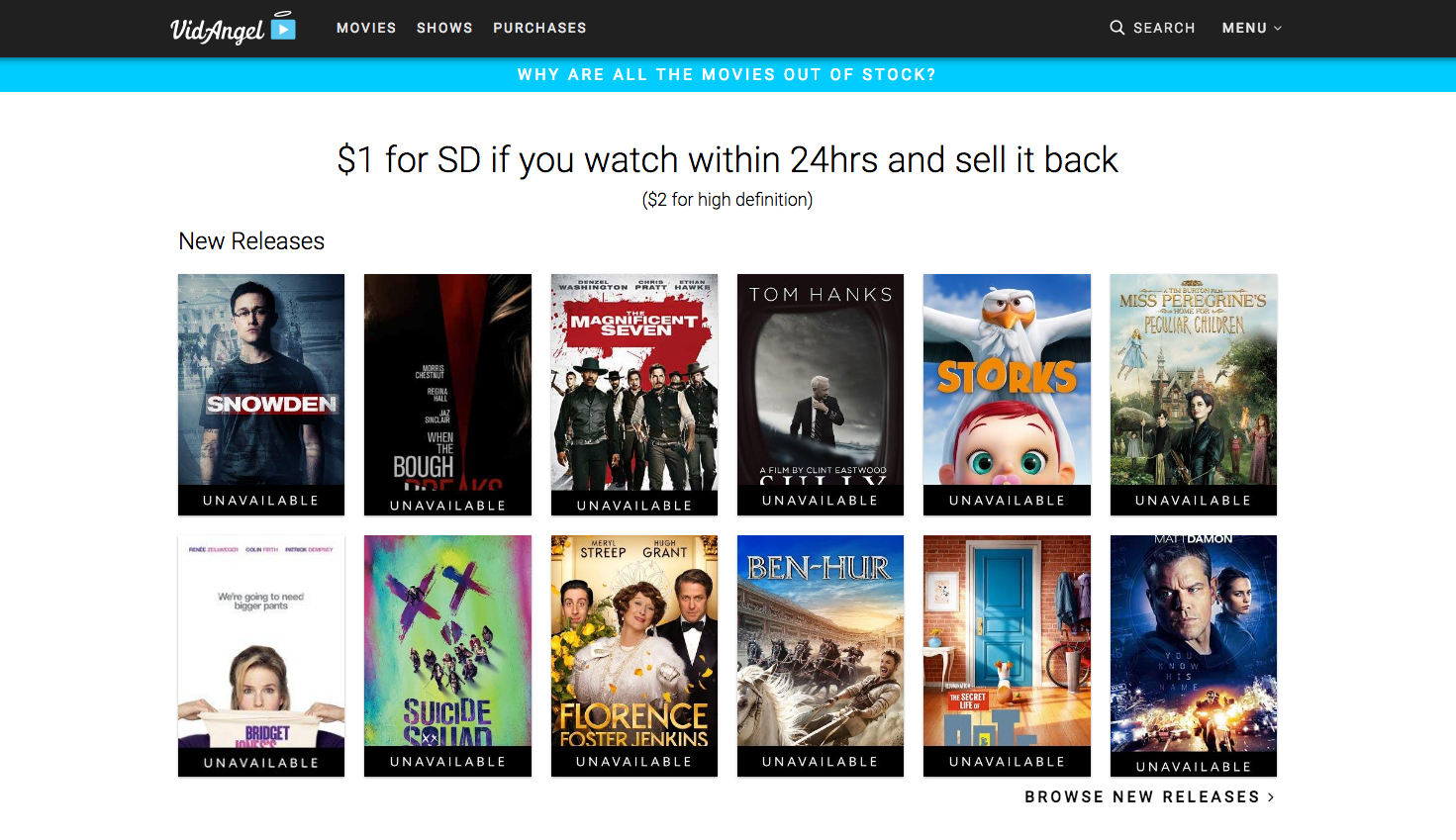

When one of VidAngel’s 1 million subscribers streams a filtered program, he or she initially purchases it for $20, chooses the filters to apply to the movie and watches it in the privacy of his or her own home.

Once viewers finish the program, they are given the option to sell it back to VidAngel for $19 credit. This means the customer only pays $1 for the program — much less than competitor streaming services charge for digital rentals. Amazon and iTunes charge around $4.99 per rental.

VidAngel carries physical DVD copies of each program that is streamed. The company monitors the DVDs and assigns a copy to each customer that makes a purchase.

Harmon doesn’t believe VidAngel needs individual licenses from the studios to legally operate as a business.

“The thing is that every company who’s tried to license for filtered content, filtered in their own home, has never been given a license, and the Family Movie Act was created to provide a way for people to do it without having to have a license from the studios,” Harmon said.

However, the studios suing VidAngel don’t believe the company is so sincere in its call for filtering. In legal documents cited by the Los Angeles Times, the studios said VidAngel is merely using filtering as a clever justification for sidestepping the law.

“VidAngel continues to invoke the Family Movie Act to distract from its unauthorized activities,” said representatives from Disney, Fox and Warner Bros. in the documents. “Plaintiffs are not challenging the (Family Movie Act); rather, they are challenging VidAngel’s unlicensed streaming service.”

The studios deny that VidAngel is authorized to stream the programs in the first place, let alone for just $1 per streaming.

VidAngel claims the studios’ narrative has been created in an effort to shut the company down, Harmon said. Furthermore, Harmon said the company has tried to work with the studios and buy streaming licenses more than once, but the studios refused.

BYU digital humanities professor Jeremy Browne said he thinks VidAngel will lose the legal case against it.

“The wording of the preliminary injunction makes it clear that the judge has accepted the argument that VidAngel creates an unauthorized copy of a movie in order to stream it to the consumer,” Browne said. “Because the 2005 Family Movie Act specifies that filtering must be done on an authorized copy, VidAngel’s appeal to the (Family Movie Act) is moot.”

Despite the lawsuit, VidAngel has gained support as it battles Hollywood to keep streaming alive. Thousands of religious leaders, members of congress, its users and community leaders, such as ex-football player Bryan Swartz, have rallied to #savefiltering.

According to VidAngel’s website, 7,554 supporters have invested over $10 million collectively in the company. BYU alumnus James Parker was one of the investors.

“VidAngel allows me to maintain my personal standards for media and exercise my right to watch what I want, how I want,” Parker said. “I invested in them because I truly wanted to see them succeed. I even donated to them before investing in them was an option.”

VidAngel could get word soon whether its offered programs will go back up on its website, but the entire legal process may take years.

Harmon urged his users to be slow to pass judgement on the situation and see what the courts decide.

“It’s a beautiful thing,” he said referring to America’s court system. “Neither the studios nor VidAngel at this point are right or wrong; we just feel that we have the most common sense perspective and I think at least the filtering users would agree.”