On the beach of Carpinteria, California, Jani Radebaugh and a group of students and faculty from BYU’s Geology Department took their lunch break as towering waves crashed into the sand.

Leah Devore, the videographer for the Geology Department shared an experience on the beach perfectly encapsulating Jani Radebaugh’s passionate and inviting nature.

“I want to get in, but I’m scared!” DeVore recalled saying. “It’s so cold!”

Always looking for an adventure, Jani Radebaugh took her hand saying, “Don’t be!” and only paused to time the jump into the swell. “Now!” she said and dove headfirst alone.

Moments later, the breakers violently washed her back to shore. “You were right to be scared,” Radebaugh said.

Jani Radebaugh is a planetary scientist and professor of geology at BYU.

She teaches a variety of courses for both seniors and freshman, non-majors and graduate students ranging across different topics in geology but focused on planetary processes.

“I love interacting with the people at BYU. Students are so bright and hardworking and really eager to do well and head out in the world and do good things,” Radebaugh said.

In terms of being a woman in a male dominated field, Radebaugh said she considers herself lucky to have had the mentors she did. Strong scientists, both women and men, blazed a path for her to show her what was possible.

“I never felt that anything was impossible for me to do,” Radebaugh said. “I’ve always thought I could do whatever I wanted, that the limits were not there on me, and I just probably have all the others who went ahead of me to thank for that.”

Working with Radebaugh has been inspiring for DeVore.

“Jani is a role model, for sure, for all of her students,” DeVore said. “She’s very independent, and she’s kind of a go-getter.”

DeVore said she admires the way Radebaugh has built a career for herself in something she is so passionate about and has been since she was young.

“She respects herself and she respects everyone around her, and that makes you want to respect her,” DeVore said. “She’s so cool, honestly, like she’s a girl boss … I want to be her when I grow up.”

But as a child, Radebaugh wanted to be Luke Skywalker.

“I was always interested in just exploring space, and just thought that sounded really exciting,” Radebaugh said. “I was really hopeful to be an astronaut and tried to figure out a good pathway to get to that point.”

As an undergrad, Radebaugh’s first exposure to science research projects at BYU was a student run project called GoldHelox. The project involved developing a soft X-ray telescope intended for the NASA Space Shuttle to study solar flares.

Teaching was never really in her plan, but as she finished her doctorate at The University of Arizona, she was invited to speak at BYU and offered a job.

Many of Radebaugh’s colleagues also worked at universities, so she decided to try it out for a while.

She found that teaching has allowed her the freedom to choose what to study while still being involved in space missions.

“I just found that was a really good fit for me, and I enjoy being around the students and teaching and having them influence my research and helping me do good work that way,” Radebaugh said.

One of her students, Rachel Seibert, a senior in geology, plans to pursue a career in groundwater research. Not only has she learned geological lessons from Radebaugh’s courses, but she said she has been inspired by the life of her professor.

“I really admire Jani, she has a lot of real world experience and has shown me so many things that are possible with geology,” Seibert said.

To involve her students in current research, Radebaugh has them study images taken by spacecraft of the landscape of Jupiter’s moon Io and Saturn’s moon Titan, Pluto, Venus and Mars. Students consider formation processes and apply that research to Earth.

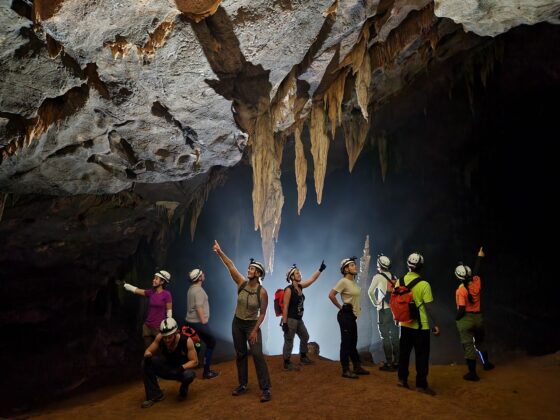

“We go to other locations on Earth that are good analogs for what we see on other planets, so you can kind of have a tangible approach to your understanding of other bodies,” Radebaugh said.

Jason Barnes, a physics professor at University of Idaho and colleague of Radebaugh’s, said he appreciates her approach to planetary science and her pursuit of Earth analogs and Earth processes that occur on other planets.

Radebaugh finds and incorporates those analogs into her science to compare what people see from NASA missions like Galileo and Cassini, Barnes said.

“She goes to great lengths to actually bring other researchers out into the field to see analogs as well,” Barnes said. “When we spend so much time looking into computers, I find it critically valuable to actually get out to see what planets look like in-person, and Dr. Radebaugh drives us all forward by finding those analogs and getting us out to see them.”

Field studies and conferences often take Radebaugh around the world. On multiple occasions, she has visited all seven continents in a single year.

“I think that feels like real exploration, because you can even explore on Earth — it’s a planet too, and has really unique landscapes and many places we don’t understand very well.”

Radebaugh enjoys traveling to remote locations — the uninhabited ones are the most like other planets, she said.

She has traveled for weeks to reach Antarctica in order to search for and collect meteorites for NASA and the Smithsonian.

“Not only are you exploring in a very difficult and remote location, but you’re finding pieces from outer space,” Radebaugh said. “So, in many ways, you really do feel like an astronaut.”

Sam Biggs, a senior in applied physics, is grateful for Radebaugh’s influence on his academic career.

“Jani turned my interest in geology into a passion and a pursuit of geophysics,” Biggs said.

Radebaugh’s international research inspired him as did her care for his understanding of the material, despite his lack of prior geological experience. She later invited him to field research trips and provided connections that led to an internship at NASA.

“Her knowledge and excitement for the subject converted me to a planetary scientist and I couldn’t be happier,” Biggs said.

Radebaugh said she looks forward to the progress of NASA’s Dragonfly mission and for opportunities to share and promote discovery.