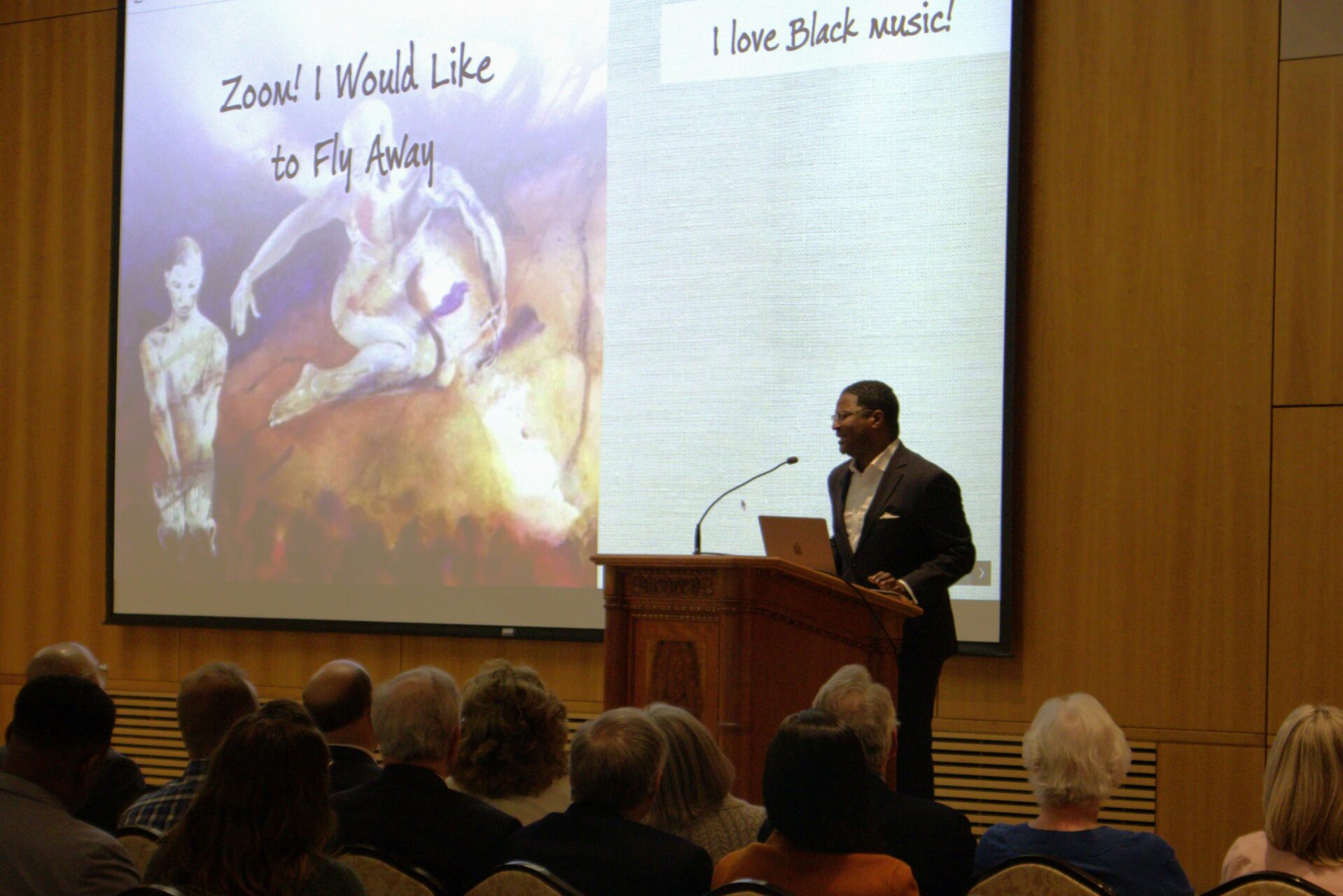

Princeton Theological Seminary President Jonathan Lee Walton gave BYU’s 7th Annual Interfaith Harmony Week lecture on Feb. 1, discussing Black religious history.

Walton is a social ethicist and religious educator. His lecture, “I’d Like to Fly Far Away! Black Religion and the Quest for Black Freedom,” focused on the history of Black migration and how it has affected music and religion within Black culture.

Grant Underwood, Richard L. Evans Chair of Religious Understanding at BYU, said he chose Walton to speak at the lecture because he’s been impressed with Black religion over the years.

“There’s a vibrancy and a vitality and a spirituality that is an American treasure,” Underwood said. “I wanted to find a wonderful representative of that who I knew not only had that faith and understanding, but had that ability to powerfully deliver and communicate that spirit.”

Walton began his lecture by thanking BYU for doing God’s work.

“The way that you are leveraging the generosity of the Richard L. Evans family, and thus the Richard L. Evans Chair of Religious Understanding here on this campus to promote inter-religious understanding and foster interfaith, goodwill, is something that I believe, I know that we should all celebrate,” Walton said.

Walton expressed his love for Black sacred music and how people of African descent have conveyed their struggles and hopes using their instruments, their bodies and their voices.

Walton then explained how analyzing an era’s music reveals the myths and rituals that have led people to persevere when faced with uncertainty and moral catastrophes. Walton said religion binds people to its values and to each other.

“Religion is that which we deem sacred, which has ultimate value, ultimate meaning so that we never conflate or confuse the quotidian rhythms of daily life with something greater that can direct our minds, our hearts, our spirits,” Walton said. “Something greater than we can see.”

The song “Zoom” by Commodores was the basis for much of Walton’s lecture. He often repeated the lyric, “I’d like to fly far away from here.” Walton said the violence directed towards Black people in Tuskegee, Alabama around the time these band members were coming of age influenced the song’s lyrics.

Walton connected the song’s lyrics to a tradition of flying Africans in Black folklore.

“It was believed Africans took off in flight in order to escape the shackles and chains of the North Atlantic Slave Trade,” Walton said.

Walton discussed the Great Migration of the 20th century within African American culture. Religious diversity, Walton said, was magnified through this widespread movement.

“Songs and sermons of Black folk in the period talk about the importance of just getting away,” Walton said. “Mobility is seen as a mark of the sacred. It’s freedom to move. It’s freedom to be what God has called us to be.”

One of the major factors of this widespread movement was the lynching of African Americans. The vast majority of lynching victims were African American men, he said.

“3,396 are known to have been lynched between the years of 1882 and 1930, and we know these numbers are woefully underreported,” Walton said. “Between the 1880s and 1930s, every five days in America, an African American man was rounded up by a mob without a trial and publicly tortured and mutilated.”

Walton explained African American and Jewish faiths have been interrelated through the enslavement of Black people in America and of the Hebrew people in Egypt. He called Harriet Tubman “the Moses of our people.”

Walton mentioned the idea of proto-nationalist religious movements among Black people, discussing how some Black people started identifying with other religious and ethnic groups, including Judaism and Islam.

Iva Hatch, a freshman studying elementary education, said she attended the event for her World Religions course.

“I really enjoyed the topics of diversity … understanding other people’s perspectives and … inclusion,” she said.

Walton said he celebrates faith communities that accept existential ideas of freedom.

“It’s a freedom that’s born of a self-conception of knowing who you are and knowing whose you are,” he said.

Walton also shared a statement his grandfather told him: “It’s not about what folks call you, it’s about what you answer to.”

Walton’s concept of existential freedom allows him to see the divine in everyone regardless of race, ethnicity and ideology, he said.

“My Christian faith teaches me that each of us has a moral responsibility to see and affirm the divine in each other,” Walton said, concluding his lecture.

Believing every life has the same value, no matter what religion, is what interfaith harmony and understanding looks like, he said.

To find more Black History Month events, visit the Multicultural Student Services website here.