See also: Preparing exhibitions is a multi-faceted process at BYU’s Museum of Art

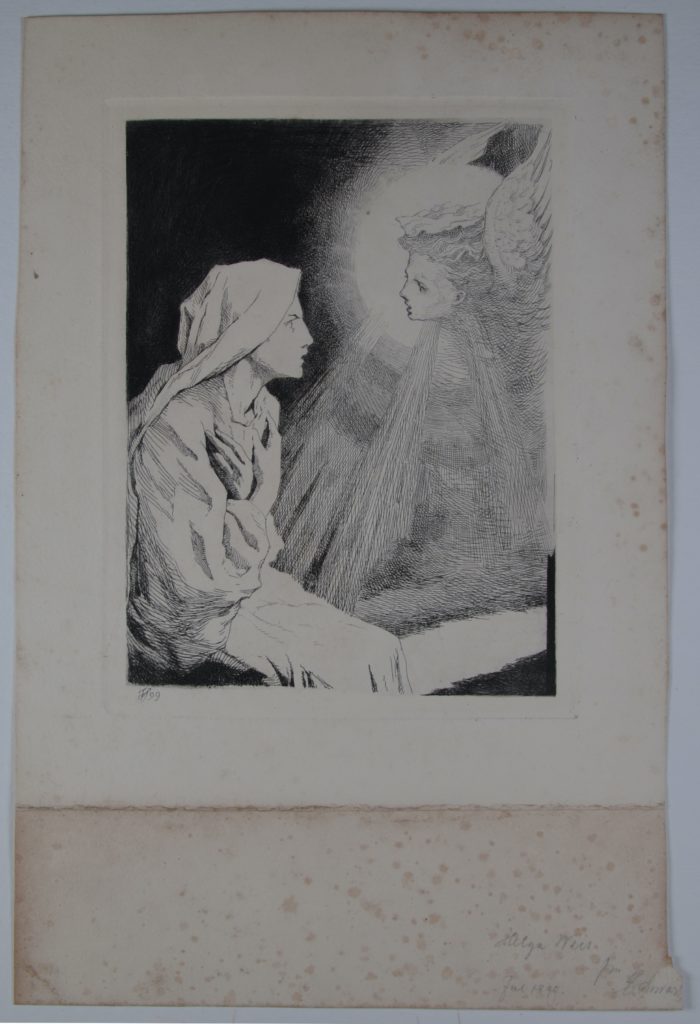

Before conservation (Frans Schwartz (1850-1917), Annunciation, 1899, etching, 8 1/16 x 6 1/16 inches. Brigham Young University Museum of Art, 2014.) (Photo courtesy of Christina Thomas)

After conservation (Frans Schwartz (1850-1917), Annunciation, 1899, etching, 8 1/16 x 6 1/16 inches. Brigham Young University Museum of Art, 2014.) (Photo courtesy of Christina Thomas)

When art on paper arrives at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art (MOA) damaged, it’s often sent to be restored before being added to an exhibition.

Christopher McAfee, head conservator of rare books and manuscripts at the Harold B. Lee Library, restores many of the MOA’s art on paper.

“In the library, we’re book and paper experts, so that means that we might repair a tear or fill a hole in the paper,” McAfee said. He and other conservators will remove stains by immersing the paper in deionized water “and sometimes an alkalizing bath as well.”

Paper that has darkened is bleached back to its original color with a light, similar to a plant light, while it is immersed in the same water it’s washed in. To ensure the paper doesn’t overbleach, McAfee will watch the paper all day and remove it when he leaves in the evening.

In a paper titled “Bleaching Paper in Conservation: Decision-Making Parameters,” art conservation researcher Irene Brückle says “a common concern is ‘overbleaching’ which means that the paper is brightened too much; and that an unwanted color shift occurs.” She explains that the excessive color shift makes the paper lose its slight “warm” yellow tone.

McAfee said he tries to avoid using chemicals to remove stains on paper. Christina Thomas, another BYU conservator of rare books and manuscripts, attended a conservation workshop and learned how to use a food additive called gellan gum to remove stains.

“We can lay the paper on it and it will absorb the stain out,” McAfee said.

According to McAfee, Thomas and a student used the gellan gum to remove a tideline — a stain that looks similar to sand when water washes up on a beach.

“If you have a document that’s just gotten dirty over time and then you get a drop of water on it or it gets water on the edge, the water will push the dirt out to a point and then as it dries, it’ll leave a dark line there,” said McAfee. He explained that as the dirtied paper is placed on top of the clear gellan gum, the dirt from the paper can be seen “penetrating” the gum.

However, paper doesn’t only come into conservation stained. It can also be torn or fragile.

“If we have a work on paper right now that’s like really, really fragile on the edge and is starting to break, they’re going to stabilize it by putting another piece of paper on the back so that it doesn’t continue to break off,” said Tiffany Wixom, Museum of Art collections manager. The art on paper will often have to be backed with a material such as Japanese paper — a thin strong paper made with long fibers.

“Your goal is to sort of lock everything in place (and) in time,” McAfee said. “From the time it came into the museum, you want it to look the same when the museum is gone — if the museum is ever gone.”