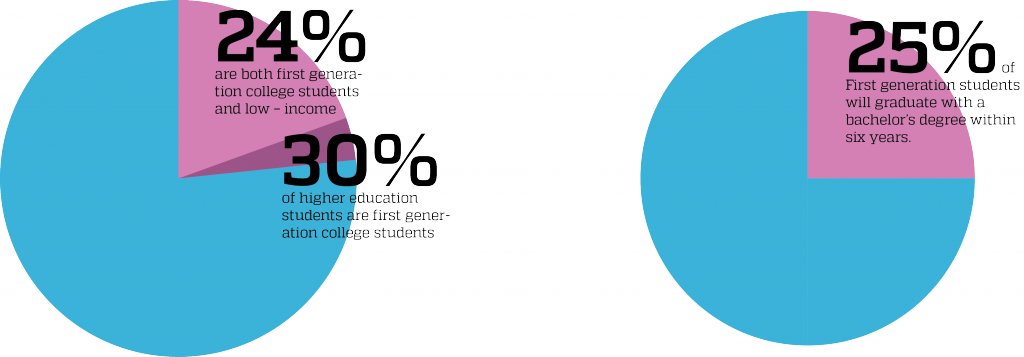

Thirty percent of enrolled college students today are the first in their family to pursue a higher education while 25 percent of them go on to earn a bachelor degree, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Ivy League schools have recently organized programs to support these first generation college students.

First generation students are slowly making an effort to retain these enrollment rates and bring awareness of the major differences they experience compared to the rest of the student body.

A BYU sociology class on inequality and social class recently required students to interview a first generation student to understand and connect with current social issues that exist in society. The class was taught by sociology professor Ben Gibbs.

“When you enter into college, it’s not like the race begins. In fact, that’s two decades after the gun went off,” Gibbs said. “For a lot of students, the differences in their upbringing in their lives begin very early in life and it’s not just about having the human capital, or the cognitive skills.”

Gibbs explained students who come from a more privileged background tend to ignore the invisible benefit of not having to choose whether or not to come to college because of living in an educated household. Other students who are the first to consider and make the decision to come to college do so with no expectation set.

Alexandra Melendez, a junior in dietetics, is the first student from both sides of her family to ever attend a college. Neither of her parents finished high school and immigrated to the United States from El Salvador and Mexico at young ages.

“My parents always encouraged my siblings and I to do really well in school so that we wouldn’t have to struggle the way they did growing up,” Melendez said. “Their examples of hard work and sacrifice has motivated me to excel so that one day I can give back for all they did for me.”

She said no one in her family knew anything about applying to college. Church leaders and family friends gave her advice to know what classes to take and how to start. Melendez and her two younger sisters currently attend BYU with financial aid and college scholarships.

Jacob Rugh, a sociology professor, said first generation students are more likely to be a minority and of a lower financial class. He said they often struggle to adjust to the college setting without a family relative to relate to.

“Almost everybody at BYU knows a BYU alumni; whether they know someone in their ward back home or someone in their family,” Rugh said. “If they knew one or two people that’s not a lot. But if everybody in their family went that’s a different advantage.”

A senior graduating in public health from the Dominican Republic, Angela Martevilla came to BYU four years ago as the first member of her family to ever attend school in the United States. She said she had a hard time adapting to a new language and culture.

“My dad prepared me for college. In high school he taught me to read ahead, be prepared for everything and have good grades,” Martevilla said. “I used the skills he taught me and that helped me to adjust.”

She said she feels she has made her parents proud now that she will leave BYU with a degree. She also said her degree is not only a personal effort “but theirs as well.”

Like Martevilla and Melendez, Stefan Davidson was encouraged by his parents to attend college for a better future and successful life. Davidson is a freshmen and the last sibling in his family to attend BYU.

Davidson’s parents never earned a college degree but always supported their children as many of them went on to Ivy League and graduate schools.

“I actually considered not going to college, and starting my own business because that’s what my dad did,” Davidson said. “I’ve always had the idea of going but I didn’t decide of actually going until I saw my older brothers and sisters going and had success in school.”

He said he now sees the struggle his parents have in deciding to further their education now that their children are older. Like Melendez and Martevilla, Davidson looked for opportunities in high school to prepare for college.

The three students gradually learned about networking, on-campus resources and good studying skills to maintain high grades and qualify for scholarships as well as future career opportunities.

While first generation college students like Davidson followed their sibling’s decision to attend college, others set the expectations for their younger siblings like Melendez.

Gibbs and Rugh agreed on the concept of the importance of a role model for any first generation college student. They both said the LDS culture that exists at BYU is a necessary assistance for those with no knowledge of how to go about finding a career choice and succeeding in their decision.

“It’s a story of resiliency, grit, developing strength in face of hardship. A sense that they sacrifice more and they own it more as a result,” Gibbs said. “Most of these cases benefited from someone in their life.”

He said every student faces constraint and agency in their lives, which potentially influence future decisions. He said although anyone has the choice to go to college, not all recognize they have the agency to do so.

“There’s always choice, it’s just some groups inherit more opportunity than others. That opportunity doesn’t determine who you become,” Gibbs said. “Students are choice-driven, some more than others, which means some have to work harder than others.”

Rugh mentioned it will be even harder for lower class, first generation students to be accepted into BYU as the admission percentage has dropped to 47 percent.

“It’s getting more selective. That means every year it’s more likely students will come from a more affluent family or a more affluent school district. So that contrast between an average and first generation student might be even greater in time,” Rugh said.

BYU spokesperson Natalie Tripp said although the university doesn’t have a quota or ratio for admitting specific demographics, administrators are aware of the “unique dynamics” of first-generation college students.

“(BYU’s) admission committee looks for qualified students of various talents and backgrounds, including geographic, educational, cultural, ethnic, and racial,” Tripp said “(The admission committee) uses a holistic review to select individuals who will create that desired mix of students.”