Eds: Undocumented students are referred to by their first names to protect their privacy.

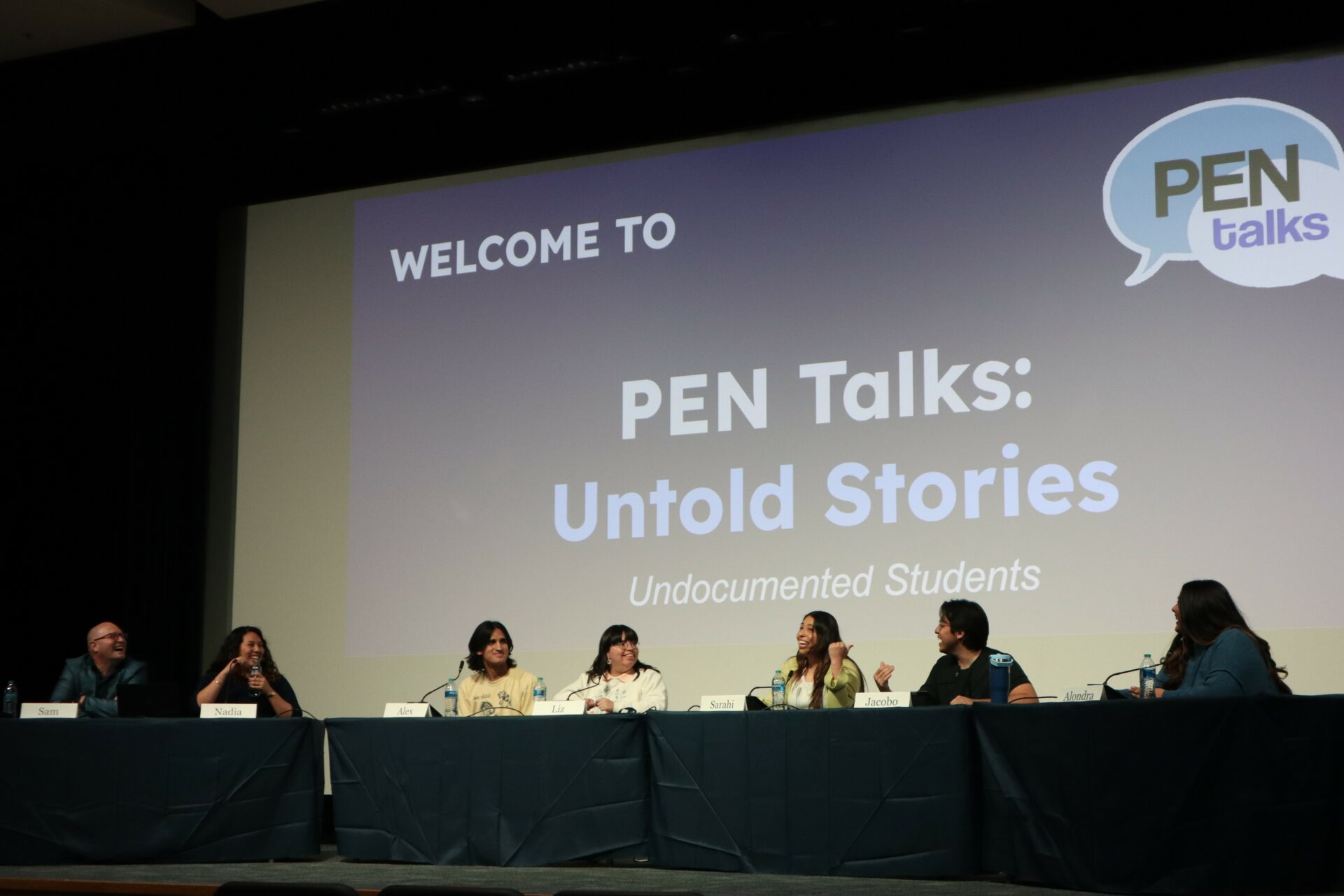

A crowd gathered at the WSC Varsity Theater to hear a panel of undocumented students and DACA recipients share their experiences growing up in the U.S. and attending BYU.

The panel was a part of the PEN Talks series. During the event on April 11, panelists talked about what being undocumented means and the struggles that come with it; they also offered advice to other undocumented students and shared how the gospel has impacted their experiences.

According to Sam Brown, director of BYU’s International Student and Scholar Services, the term “undocumented” refers to those who have either overstayed their visa or were not processed by Customs and Border Protection when crossing the country’s borders.

DACA stands for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which defers removal action for some of those who came to the U.S. as children, according to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. DACA recipients can have the right to be employed in the U.S., but DACA is not a pathway to citizenship as some may think, Brown said.

Jacobo, a senior studying business at BYU, is a DACA recipient. He shared he has a two-year work permit through DACA which restricts him from making future plans.

“This makes it really, really hard to make plans for jobs or relationships or anything that you might think, ‘Oh, in the future, I’ll do that,’” he said. “We have to think in two-year terms because you don’t know when, if or how you could be removed from the country at a given moment.”

Sarahi, a graduate student at BYU, echoed this feeling of limitation.

“Growing up in L.A., it’s like, ‘Dream big, the sky’s the limit,’ but for us, a paper is the limit or the policy is the limit,” she said. “You’re constantly taught to dream big but thinking about, ‘Oh, are we going to lose it in two years?’”

When asked how they felt when they first learned about their status, Jacobo recounted the story of when his father was deported from the U.S. Jacobo was 11 years old.

“I haven’t seen my dad since,” Jacobo said. “That’s the moment when it really hit me that, ‘Huh, I’m not safe and none of my family is safe, and we will never be safe.’ Growing up like that is traumatizing, knowing that at any given day you could be ripped apart from your family.”

Alex, a BYU senior, said there was a lack of representation for undocumented students when he first arrived at BYU. However, he said the Office of Belonging has become a safe space for him to see others who are like him.

Jacobo addressed the misconception that undocumented students take federal aid or pell grants when, in fact, undocumented students do not qualify for either.

Liz, a freshman studying sociology, said others often think undocumented students don’t try or don’t work hard enough.

She said she has often heard others question why someone would come to the U.S. undocumented, asking “Why didn’t you guys do it this way? My friends did it this way, why didn’t you guys do it this way?”

Liz shared how in five days, she was set to lose her job because of her employment authorization document card not arriving in time. She expressed that those who are undocumented are trying their best.

Sam Brown then directed the audience to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services visa bulletin.

“You can see the exact day that they’re adjudicating applications for immigration visas, and in most cases it’s 19 and 20 years of a wait just for the adjudication,” Brown said.

Alondra, a graduate student finishing her master’s in social work, discussed her struggles with dating as an undocumented student.

“I had somebody else tell me, ‘I think I have to date you for six months to feel comfortable enough to feel like I can trust you, to feel like you’re not in it for another reason,’” she said.

Alex said while being an undocumented student can be lonely, he reminds other undocumented students that there are people who will love them for who they are and vouch for them.

“Once you have that community, it’s literally like the world is lifted off your shoulders, so absolutely find your people,” Alex said.

Sarahi advised other undocumented students to visit the Office of Belonging if they feel afraid.

“I think, most importantly, I would definitely say that you’re loved and that you’re welcomed and that you belong,” she said. “You’re here for a reason and there’s people that are willing to help you out.”

Jacobo said while he was very cautious growing up and constantly looked out for himself and his family, he has seen the hand of God help him throughout his struggles.

“I have seen Him guide me through the hardships, the dark times, through loneliness, the depression,” he said. “He has guided me to people who have helped me, who have helped me find my voice, who have helped me advocate for others.”

Sarahi said she doesn’t feel alone as she reminds herself that Jesus Christ was a minority as well.

“There’s these people in the scriptures that immigrated and they moved because they were led by God,” she said.

Liz said these religious figures help her find a divine purpose being in the U.S. and draw her closer to God.

She also mentioned that her relationship with the gospel of Jesus Christ has impacted her experience as an undocumented student.

“Knowing the gospel includes people like me, free or bound, Black or white, whatever it is, has been one of the reasons that I am here right now. It saved my life,” she said. “I don’t always feel like I belong. It’s hard to find that space, those safe spaces, but Jesus Christ is one of them for me.”

More resources for undocumented students can be found on the BYU Undocu-Student Support Services website.