Martin Luther King Jr., once said, “Men often hate each other because they fear each other.”

I witnessed recently, however, that fear and hatred can be overcome. That is what I learned from the Black 14 during a series of Black History Month events in Atlanta.

“It’s all about fellowship, it is about respectability, and most importantly it is about love,” said John Griffin, a former University of Wyoming football player who has joined with his one-time teammates to turn “tragedy into philanthropy” in conjunction with BYU and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “That is what we have gained through all this.”

When Griffin and 13 teammates walked into their coach’s office in Laramie, Wyoming, in 1969 to ask about wearing black armbands during a game against BYU, none of them expected to create a legacy of forgiveness.

More than 50 years later, that lesson of reconciliation and healing was on full display at the College Football Hall of Fame. In early February, I attended the Hall of Fame events where the Black 14 were honored in connection with a Black History Month exhibit on their story.

When I began my journey learning about the Black 14, I thought it was a story of football. As I boarded the plane home from Atlanta to return to Provo, I knew I had gained something so much deeper than that.

How many people in our lives are we unwilling to forgive? How much anger is stored in our hearts?

The Black 14 taught me the power that can come from every decision made in life. Brotherhood and love can be found amid the greatest tragedies.

“I have decided to stick with love,” King said. “Hate is too great of a burden to bear.”

The Events of 1969

On Oct. 17, 1969, Griffin and his teammates Earl Lee, Willie Hysaw, Don Meadows, Ivie Moore, Tony Gibson, Jerome Berry, Joe Williams, Mel Hamilton, Jim Issac, Tony McGee, Ted Williams, Lionel Grimes and Ron Hill went to Wyoming Coach Lloyd Eaton’s office. They wanted to know if they could wear black armbands in the next day’s game against BYU.

The players wanted to make a statement about what they had experienced as racist treatment in the previous year’s game in Provo. Meanwhile, members of the Black Student Alliance at the University of Wyoming had encouraged the players to take a stand against the then-existing policy of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints that prohibited Black men from being ordained to the priesthood.

Eaton, though, did not want to talk about that. Instead, he excoriated the players.

“You are no longer Wyoming Cowboys,” he said immediately, meaning the players lost their scholarships and spots on the football team. They watched the game against BYU the next day from the stands, and many of them had to leave Laramie soon after.

Not only did he dismiss them from the team, but Eaton also told the players no other teams would want them and they would be on public assistance for the rest of their lives.

“The coach told us we would never amount to anything, but we all decided we were going to do something,” Griffin said. “As the years went by, we decided to rise, and no one could take that away from us. As young Black men starting out, we beat the odds.”

Dealing With the Aftermath

Members of the Black 14 had successful careers in fields ranging from educational leadership to professional football. Although they were able to overcome the predictions of their former coach, the hurt remained in their hearts.

Hamilton recalled that he was not able to even watch a football game on television for years. Although McGee played in the National Football League, appearing in two Super Bowls, the pain remained.

“I was angry for 10 years. I never discussed it, but it was boiling inside of me,” Griffin said. “When the early 80s arrived I decided I couldn’t change history, I needed to change what I was doing.”

By 2019, the University of Wyoming took steps to apologize to the former players and welcome them back to campus. They were honored on the field before a game and were given their letter jackets. A monument was placed at the stadium in their honor.

Yet members of the Black 14 wanted to do more to leave a positive legacy. They aimed to “turn tragedy into philanthropy,” in Griffin’s words. They decided to look for ways to give back to their communities around the country.

“We were all shooting ideas around trying to figure out what we should do,” Hamilton said. “John and I were talking one night and he said, ‘I wonder whether the (Church of Jesus Christ) would help us prevent food insecurity.’”

Hamilton got in touch with Elder S. Gifford Nielsen of the Seventy. Elder Nielsen played quarterback at BYU and in the NFL, and the two bonded over football. Elder Nielsen asked Hamilton to create a proposal, which the Church accepted. For the last several years, the Black 14 and the Church have collaborated on donating hundreds of thousands of pounds of food to communities nationwide.

Reconciliation and Collaboration

Throughout the partnership between the Black 14 and the Church of Jesus Christ, moments of pain and anger can still be felt. McGee explained that some mornings he wakes up feeling no anger, and others he wakes up full of it again. In spite of the wounds still healing, the mission to educate, feed and serve underprivileged communities prevails.

“All the anger may not be gone, all the love may not be here, but we are progressing and trying to make it happen,” McGee said.

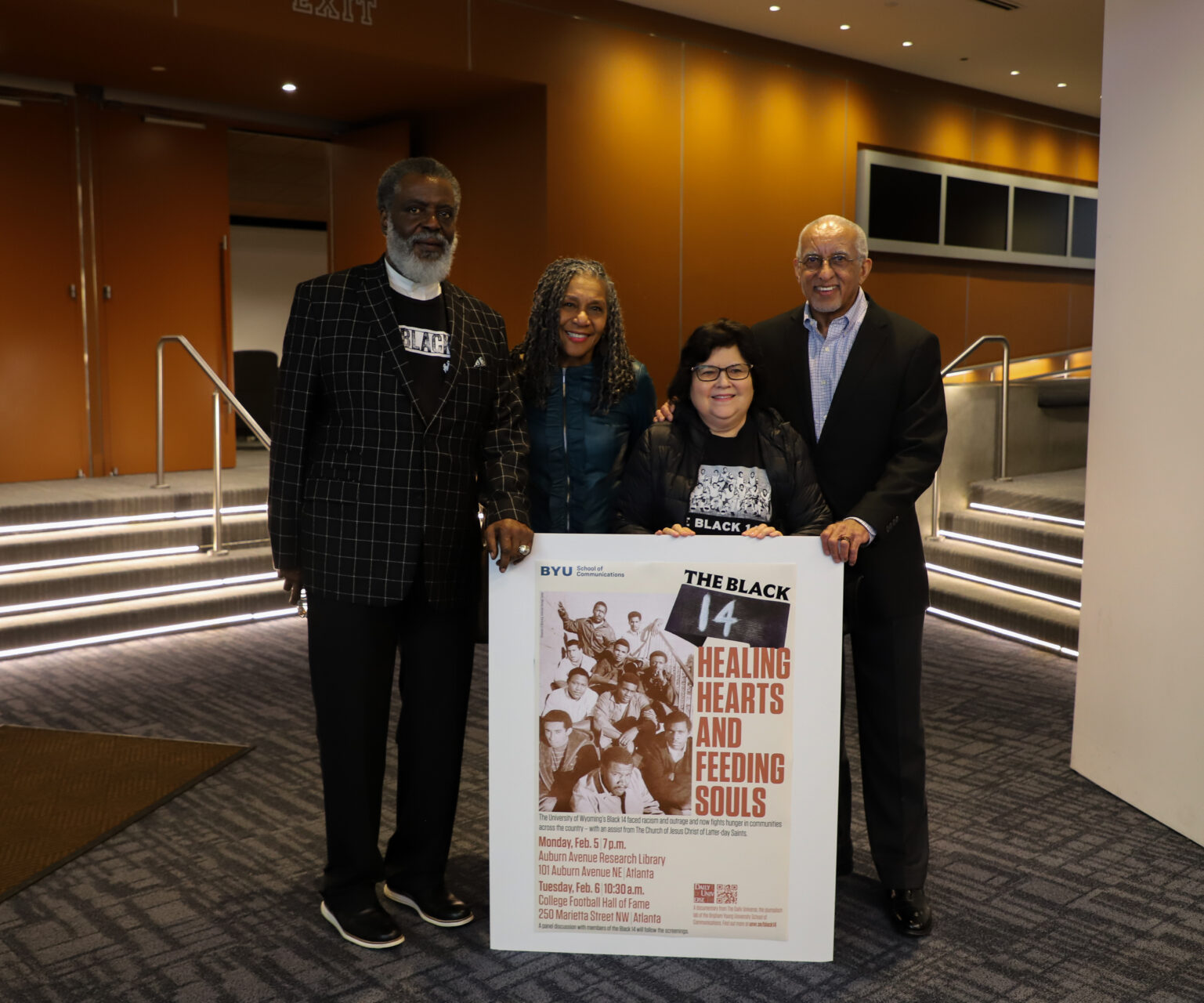

These men were recently honored at the Chick-Fil-A College Football Hall of Fame with an exhibit for Black History Month in February. Part of the festivities included airing a BYU School of Communications documentary video titled “The Black 14: Healing Hearts and Feeding Souls.”

During a panel discussion after the film, Hamilton expressed his feelings on the Black 14’s mission, as well as the experience he had as his son joined the same church he protested. Hamilton explained that, at first, his son was hesitant to tell his father about his conversion, but when he did, Hamilton expressed joy that his son could be a part of the Church of Jesus Christ and hold the priesthood. Hamilton later followed his son by being baptized.

“This is the first time I have said this publicly, but I am a member of the LDS Church,” Hamilton said at the Hall of Fame in Atlanta on Feb. 6. “I have done a complete about face, and I am very happy that I can join with my brothers and sisters to make this world a better place for all mankind.”

When Hamilton made this announcement, the feeling in the room shifted. I have never felt the Spirit of God so strongly. Tears fell from my eyes with gratitude. Hearing Hamilton tell his story of turning hatred and strife into love and conversion was an experience I will never forget.

I will forever be grateful that the Black 14 decided to let go of their burden. The world is a better place because of the forgiveness they have shown.