On- and off-campus resources offer hope and help to students who struggle with scrupulosity, commonly known as religious OCD.

Scrupulosity is when religious individuals are faced with symptoms such as obsessions and compulsions, distress and diminished functioning. According to a 2019 study by BYU student Madeline R. Christensen, scrupulosity “is characterized by a cycle of anxiety-producing fear of sinful or immoral behavior and compulsive attempts to soothe that anxiety through religious means.”

In the September 2019 issue of the Ensign, psychologist Debra Theobald McClendon said scrupulosity manifests itself in the lives of people by “relentlessly plaguing them with pathological, toxic guilt and inducing them to believe that this guilt comes from the Spirit.” Consequently, many religious actions like scripture study and prayer are done out of fear and penitence rather than to seek spiritual peace or knowledge.

Woodson Parker, an electrical engineering major and current president of the Real OCD Club, said many cases of scrupulosity are found on campus.

“OCD tends to be a disorder that latches on to the things you value … so students that are religious tend to obsess about religious topics,” Parker said. For Parker, it makes sense that there is a higher likelihood for BYU students to suffer from the disorder.

Aubree Jennings, a BYU senior from San Diego, discovered she had scrupulosity OCD when she was a freshman.

“It was a lonely and scary journey for me at times,” Jennings said.

After speaking about her difficulties with her bishop, he referred her to the LDS Family Services near campus. Through exposure therapy, group therapy and psychiatric help from the BYU Health Center, Jennings’ life began to change.

“With the support from my bishop, family and specialists, I can honestly say I’m a completely different person than I was three years ago. I have my life back and will never have to experience that kind of darkness and loneliness again,” Jennings said.

While some people may think OCD is just about cleanliness or organization, there are many different subtypes that people don’t realize exist, Britlin Alius said. Alius, a BYU junior studying experience design and management, is in the presidency of The Real OCD Club.

Alius said she is passionate about increasing awareness about scrupulosity because she wants people to know they are not alone and help them recognize the symptoms sooner so they can receive the proper treatment. Receiving treatment at the earliest stage of life possible allows those with diagnoses to retrain the pathways in their brain through therapy earlier and decrease the time they struggle with the thoughts on their own, Alius said.

“I got diagnosed when I was like in elementary school and I feel like it shows,” Alius said.

Compared to the average person with scrupulosity who is diagnosed after 14-17 years of symptoms, she said she feels lucky.

“I’m in a really good place because I’ve had that time to really understand what it is with my therapist and now I’m at a point where I’m trying to help other people which I feel is really cool,” Alius said.

Parker said he wished more people could understand what OCD really is, and how it differs from just liking things to be neat and organized.

“When you have OCD, you know what you’re doing is irrational. You also don’t like doing it. Someone who likes when things are neat is different from someone who feels intense anxiety and feels like they have to make things neat or else,” Parker said.

The Real OCD Club is a place designed to increase awareness and provide a community for those with OCD.

“When I was first diagnosed, it was very helpful to meet people who were at a similar place that I was,” Parker said.

The club is a place where students can get questions answered, and although they don’t provide therapy, they have connections with therapists and resources in the community that can help.

Broderick Brown, a psychologist for BYU CAPS, is the faculty representative for the Real OCD Club and leads the OCD group therapy offered through CAPS.

Alius said the religious atmosphere of BYU can be especially difficult for some students struggling with the self-condemning thoughts of scrupulosity.

“A religion classroom can be a very triggering place if you’re already so hard on yourself,” Alius said. For this reason, she reached out to Associate Dean of Religious Education Tyler Griffin to spread awareness of the disorder in the department.

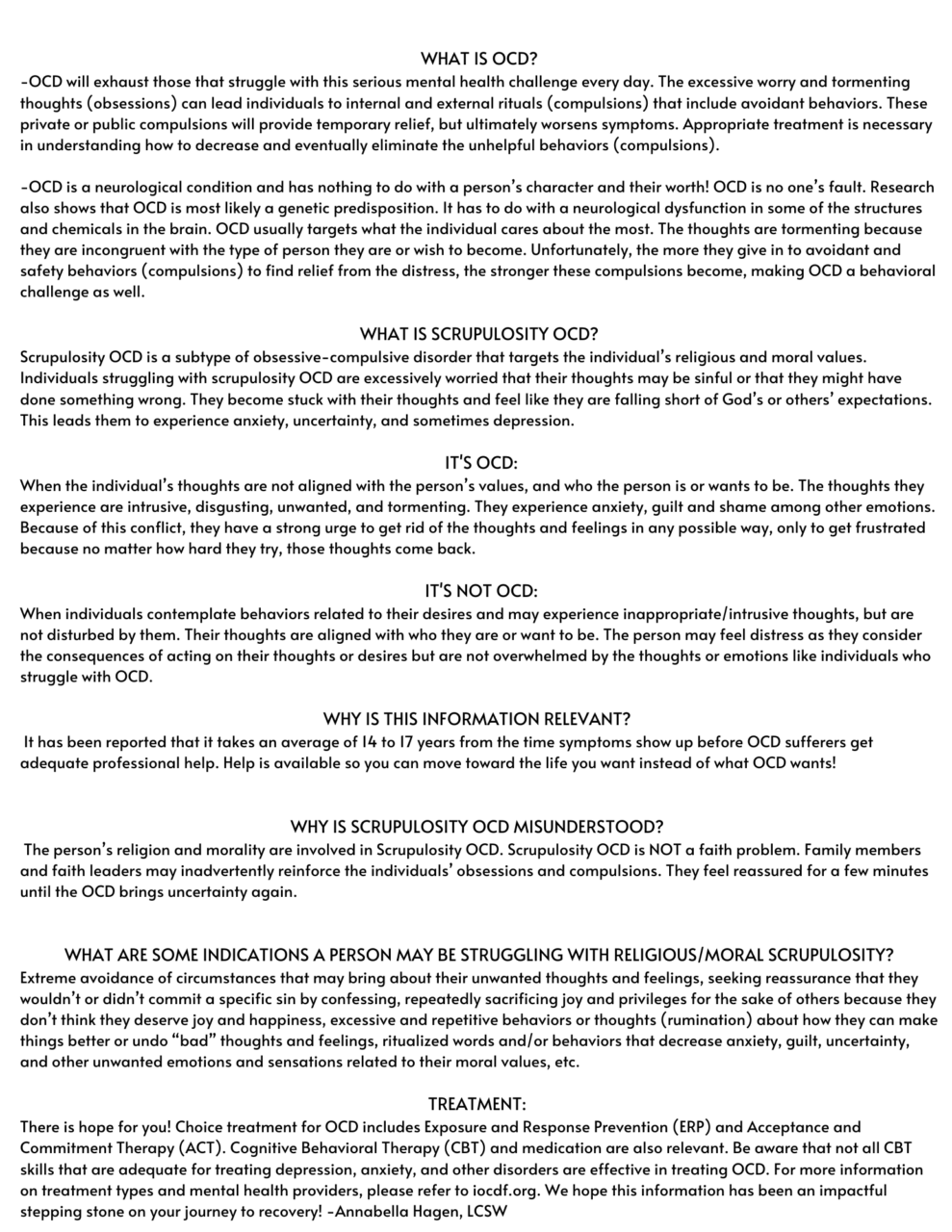

To promote awareness and education, Alius designed and coordinated with psychologist Annabella Hagen to make a flier on recognizing and managing scrupulosity.

On top of two monthly events — one in person and one virtual — the Real OCD Club hosts “Self Care Sunday,” a weekly book club of sorts discussing the topics included in the book “Imperfectly Good” by Annabella Hagen.