While Pioneer Day means family and fireworks for some, this state-recognized holiday may be more nuanced than local parades show.

Utah is home to eight tribal sovereign nations: Confederated Tribes of Goshute, Navajo Nation, Northwestern Band of Shoshone Nation, Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, San Juan Southern Paiute, Skull Valley Band of Goshute, White Mesa Community of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Ute Indian Tribe.

Like other stories of colonialism, Utah’s history is full of diverse perspectives.

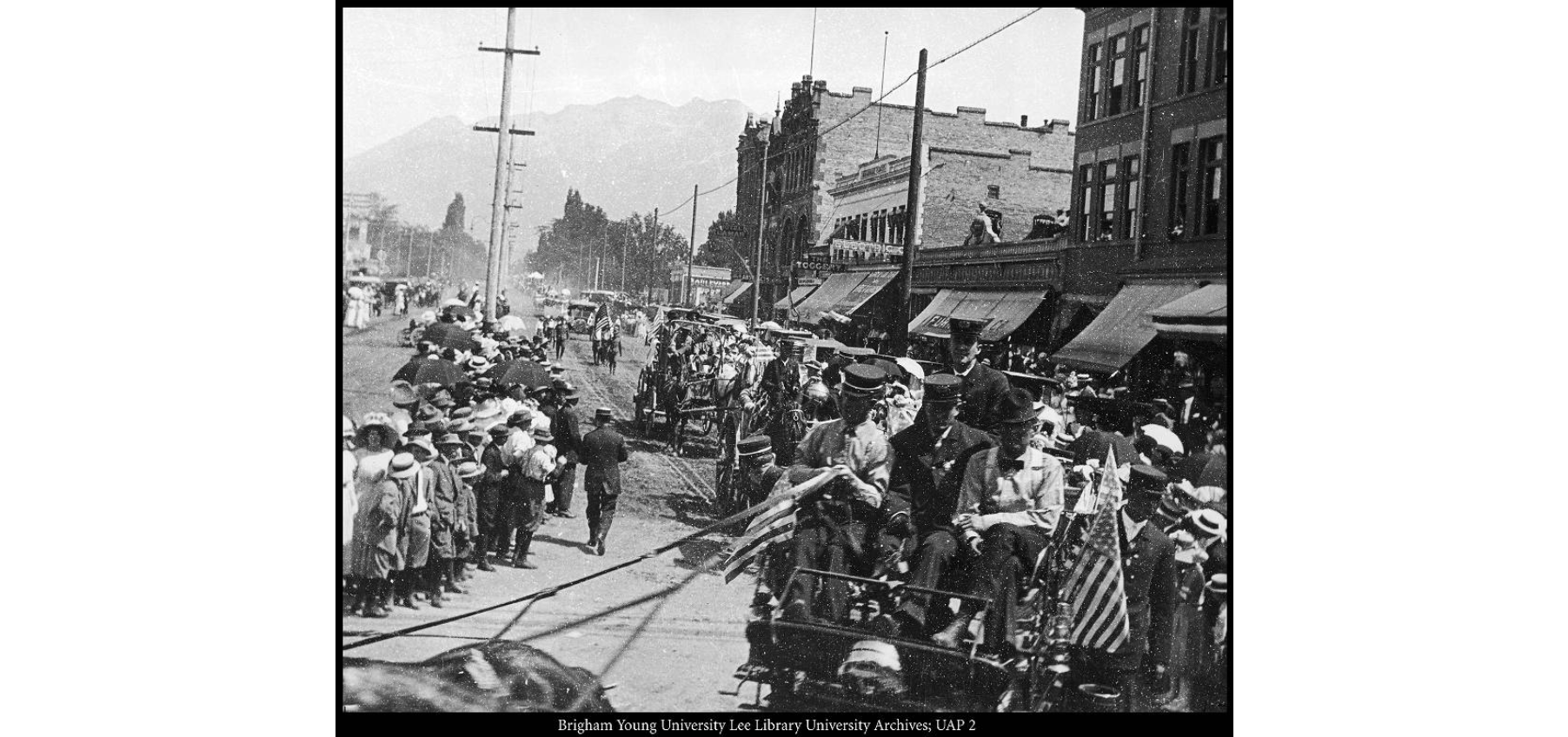

Pioneer Day History

Weary travelers took the first step toward the successful founding of a Mormon homeland on July 24, 1847, when a group of Latter-day Saint pioneers entered the Great Salt Lake Valley. Many early members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints followed the Prophet Brigham Young in an exodus across the U.S. throughout the 19th century.

July 24, 1847 officially marked Brigham Young and the first group of Mormon Pioneers’ entry into the Great Salt Lake Valley. Two years later, Pioneer Day was first celebrated in Utah. The Utah History Encyclopedia notes that some sociologists refer to Pioneer Day as “the greatest Mormon holiday.”

“From these obscure but auspicious beginnings, Pioneer Day … has grown into one of the largest regional celebrations in the United States,” the Utah History Encyclopedia said.

Amplifying Native Perspectives

However, for some Utah citizens, the holiday is about more than Utah’s first Latter-day Saint settlement.

The earliest human settlements within the modern-day borders of Utah inhabited the area between 10,000 B.C. and A.D. 400. In 2020, the Census Bureau recorded more than 41,000 Native Americans living in the state of Utah.

Dominique Talahaftewa, Hopi and Ute, is the cultural liaison for the Utah Division of Indian Affairs. She has worked with the Utah Division of Indian Affairs for more than eight years in a variety of positions.

Talahaftewa said there are many perspectives on the Pioneer Day holiday and celebrations and historical events are often sensitive subjects.

“This particular holiday holds deep meaning to many from both ends of the spectrum. And although I don’t speak for the tribes, I would like to recognize that there are eight federally recognized sovereign nations within the state of Utah,” Talahaftewa said.

She emphasized the importance of a holistic view of Utah history. Talahaftewa has seen Pioneer Day become more inclusive and hopes to see education efforts and recognition of Native American tribes improve.

“There’s history that goes beyond the (Mormon) settlement and beyond what’s happened in the last 200 years,” Talahaftewa said. “I’d like to see that education being shared and recognized with everyone from youth on up to all ages.”

Modern Pioneer Day Celebrations

Along with parades, fireworks and the grassroots “pie and beer” day celebrations, many Native American tribes gather over the Pioneer Day weekend to celebrate.

Liberty Park in Salt Lake City hosted the annual Native American Celebration in the Park on July 24.

According to their website, “NACIP is an event sharing the Native American culture through song, music, dance and drums and cultural preservation.”

This year was the 29th annual celebration of Native American Celebration in the Park.

“We ask the Native American tribes and communities to support our venue in the midst of the State of Utah pioneer day celebrations. We advocate Native American presence through a united effort,” the NACIP website said.

Members of various tribes traveled to Salt Lake City to participate. Trushayah Shi-Lovey Bitsoie and her two sisters traveled from Cedar City, Utah to participate in the celebration.

Bitsoie and her family are Navajo and sold handmade jewelry at the event. Bitsoie also performed traditional Native American dances, including the Women’s Fancy Shawl dance.

“I’ve been dancing practically my whole life. All the dances are my favorite,” Bitsoie said when asked about her dance experience.

Moving Forward

BYU Professor of American History Jenny Pulsifer said she is unfamiliar with what goes on at most Pioneer Day celebrations, but she sees her local community talking about Native American History more and more. Pulsifer said increased visibility of Native American culture and history is healing for native communities.

Pulsifer is Shoshone and holds a doctorate in American History from Brandeis University.

Pulsifer teaches courses about Native American History at BYU and described her research interests as “Native American history, Early American history, 19th century Utah, interactions between Native Americans and white settlers, race and identity.”

One of the most important issues that Pulsifer sees affecting Native American communities and local tribes is land issues. Pulsifer described the “Land Back Movement” as a movement taking place in multiple states across the U.S. where Native American Tribes are asking for land back that once belonged to them.

“Of course that’s a sore point with not just Latter-day Saint Pioneers, but any settler group coming onto Native land. Having land taken away by a government treaty or just getting crowded off, … there’s a sense that something has been unjustly taken,” Pulsifer said.

Pulsifer noted the importance of land acknowledgments by organizations. For example, a land acknowledgment occurs when leaders of organizations issue official statements acknowledging that the land owned was originally the homeland of a Native American Tribe.

“My students have told me that, that helps. Even just saying that, it acknowledges that there are still native people here and that their history is recognized,” Pulsifer said.

Pulsifer has seen more frequent acknowledgements of Utah tribes and improvements in incorporating more Native American history into BYU curriculum. She hopes to see continued gains in Native American history and culture visibility.

“When native people say, ‘Maybe we should get some land back,’ I think it’s very easy to dismiss those kinds of requests or demands and say, ‘You lost it, it’s mine and it would be unfair to take it,'” Pulsifer said. “But I think it’s worth listening and thinking, ‘Is there a way that things could get better?’”

Pulsifer recommends taking classes about Native American history, learning about native culture, acknowledging the Native American homelands and listening when native people speak up.