BYU research recently found that kids with autism spectrum disorder have better outcomes when parents are equipped to intervene at home.

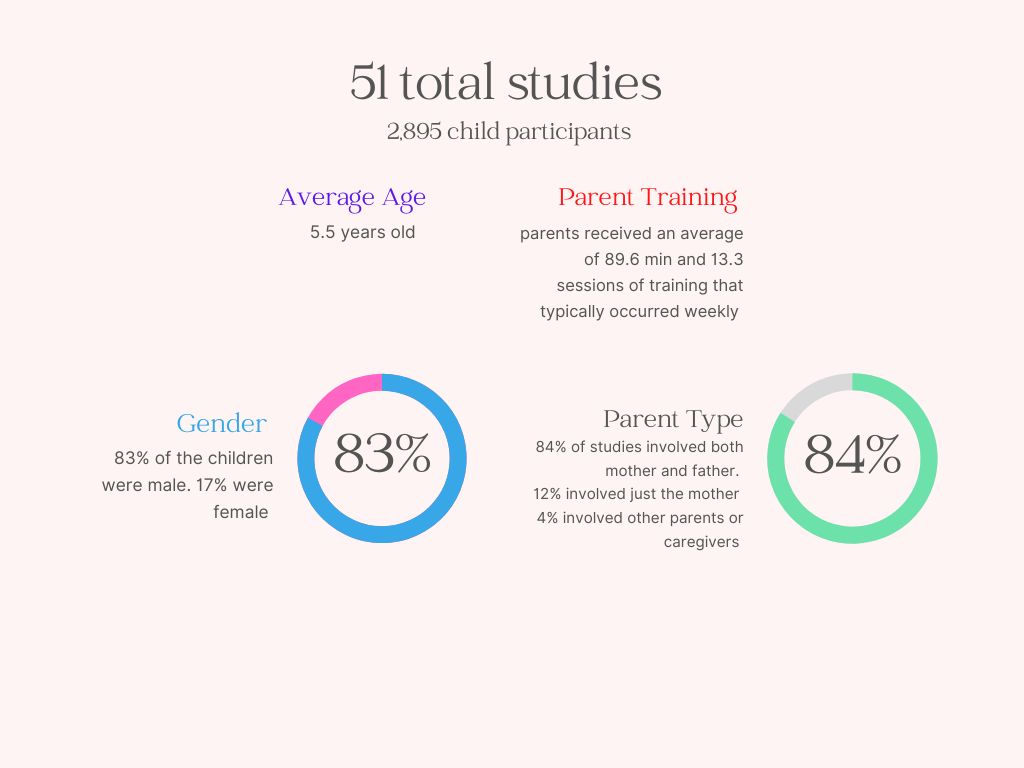

The study examined over 50 randomized control trials from around the globe, including nine studies from non-English speaking countries. The study also said it took researchers about a year to comb through the existing literature.

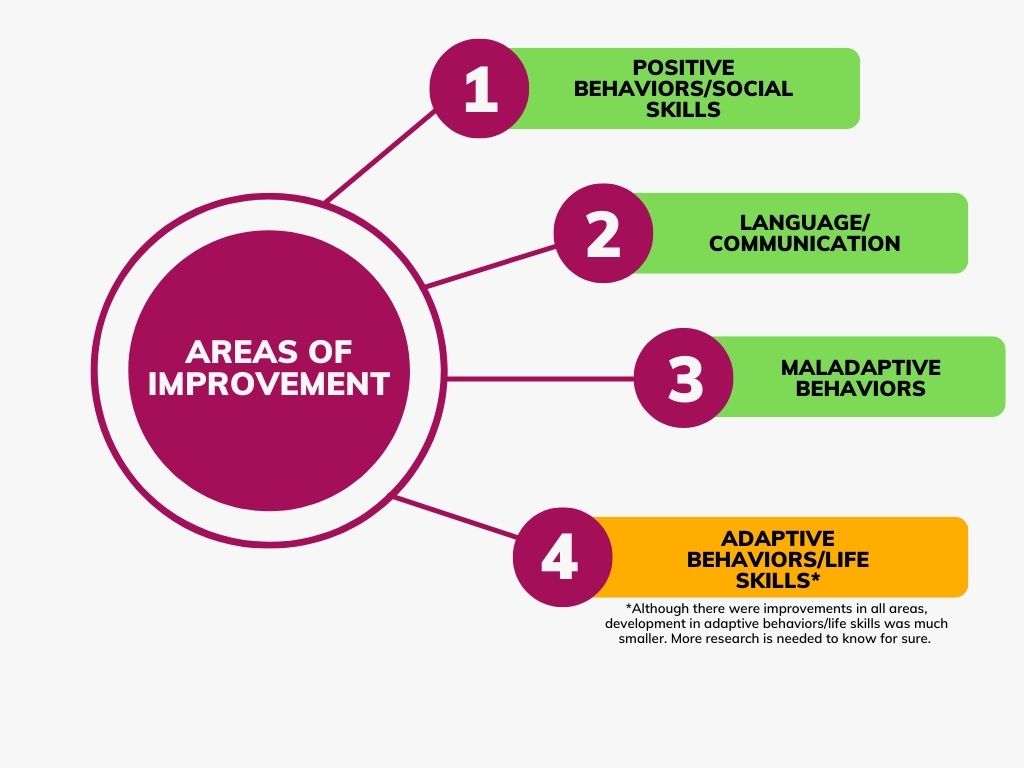

“What was surprising was that the results were so consistent,” Dr. Tim Smith, a co-author of the research, said. He and his team found that children with autism benefit from parent intervention regardless of the identity of the parent or caretaker, or the type of intervention that was used.

“It’s not what you do, it’s that you do,” Smith said. “As long as you intervene, the children benefit.”

BYU master’s student Wai Man (Linda) Cheng was the lead author of this study. The paper grew out of her master’s thesis, which was inspired by the time she spent with autistic children in China. She said she hopes her research empowers parents of children with autism to get the training they need to help their kids.

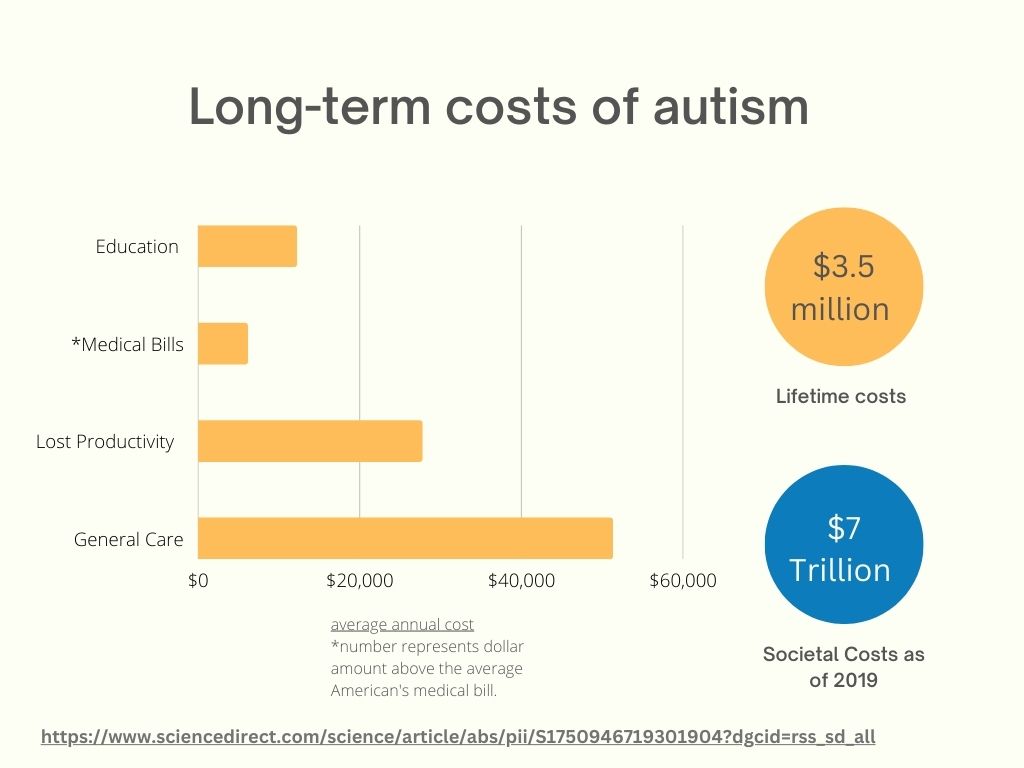

Finding professional treatment can be difficult—and expensive. Studies show the median annual cost for families treating a child with autism spectrum disorder is over $34,000. Other estimates are higher, with lifetime costs over $3 million.

Stacy Harmer is a mother to a 6-year-old adopted girl. Harmer and her family did not know their daughter had autism spectrum disorder before she came into their lives.

Harmer said she has explored many types of treatment. She has tried applied behavioral analysis therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy and ordered plenty of books about autism. Many of the treatments, she said, have waitlists.

“It’s not always easy on a day-in, day-out basis, but I try to learn as much as I possibly can to help her unique situation,” Harmer said. “We just keep trying every single day.”

Professional practitioners commonly provide intensive one-on-one sessions just a few times a week, but Cheng said she thinks this might not be enough.

“We cannot solely rely on practitioners to give the hours that the children need. It’s just impossible. We don’t have enough professional practitioners out there,” Cheng said. “The more intervention we can provide the child, the better.”

Dr. Tina Taylor, assistant dean at the McKay School of Education and co-author of the study, said interventions are most effective while kids with autism are still young. She compared early intervention to compounding interest.

“If you invest early, the effects of that early investment compound over time. So it’s a similar analogy. Invest early in a child’s education, training and learning, and over time you will see greater benefits than had you waited,” said Taylor.

One of the biggest barriers to parent-lead intervention, Taylor said, is awareness. She said some parents do not know their child has autism spectrum disorder until they are much older; and parents that do catch it young often don’t know where to go to get professional, individualized training. Taylor said this is especially true in minority and rural communities.

Cheng understands how frustrating it can be for parents to not know how to help their children. She said it should be standard procedure for doctors and family practitioners to help connect patients to high-quality, individualized intervention training as early as possible.

Smith agrees with that sentiment. “When a parent has a child with autism spectrum disorder, they don’t know what they don’t know,” Smith said. “That’s where specific information about parenting training can absolutely meet a need that is not presently being filled.” The more information parents have, the better off their children will be, he said.

Parent-initiated intervention is not a replacement for professional intervention. Rather, Cheng said, it is intended to supplement the support that trained professionals provide, giving parents the tools to address issues as they arise in day-to-day life.

“We aren’t saying that parents do it better than professionals do. What we’re saying is parents do it, and they do it well” Taylor said.

When asked if she would welcome this sort of professional training, Harmer said, “I would definitely welcome that. We really didn’t have any background on this disorder before our daughter was diagnosed, so having someone to hold my hand would have been super helpful.”

Allowing parents to intervene more effectively, and earlier, has economic implications too. Investing in early intervention programs, particularly parent-initiated interventions, could help children with autism better integrate into the school systems, the workforce and even independent living, said Smith. But, he clarified, “even more important than the dollar amount is the life potential that is lost—or gained.”

Smith said he believes people with autism spectrum disorder have much to offer society. He said helping them interact also means helping them contribute. “Our society is losing out on the depth of perspective that people with autism spectrum disorder can offer and must offer if we are really going to succeed as a society,” Smith continued.

Parents like Harmer are ready to take advantage of any available resources that will help their children reach their full potential. She said, “We absolutely adore our daughter. We’re trying to give her the resources—and us the resources—to know how to best help her grow and develop and thrive. She’s been an absolute blessing to our family.”