Written by Decker Westenburg and Marina McNairy

Fiddling with cameras and becoming experts of the mute button has become the new normal as Utah lawmakers convened at home during a historic special legislative session April 16, 17 and 23.

During the typical 45-day legislative session, lawmakers, lobbyists and residents flock to the state capitol. Due to the stay-at-home order across the nation, lawmakers swiftly tried to create a similar remote experience to what normally happens on Salt Lake City’s Capitol Hill.

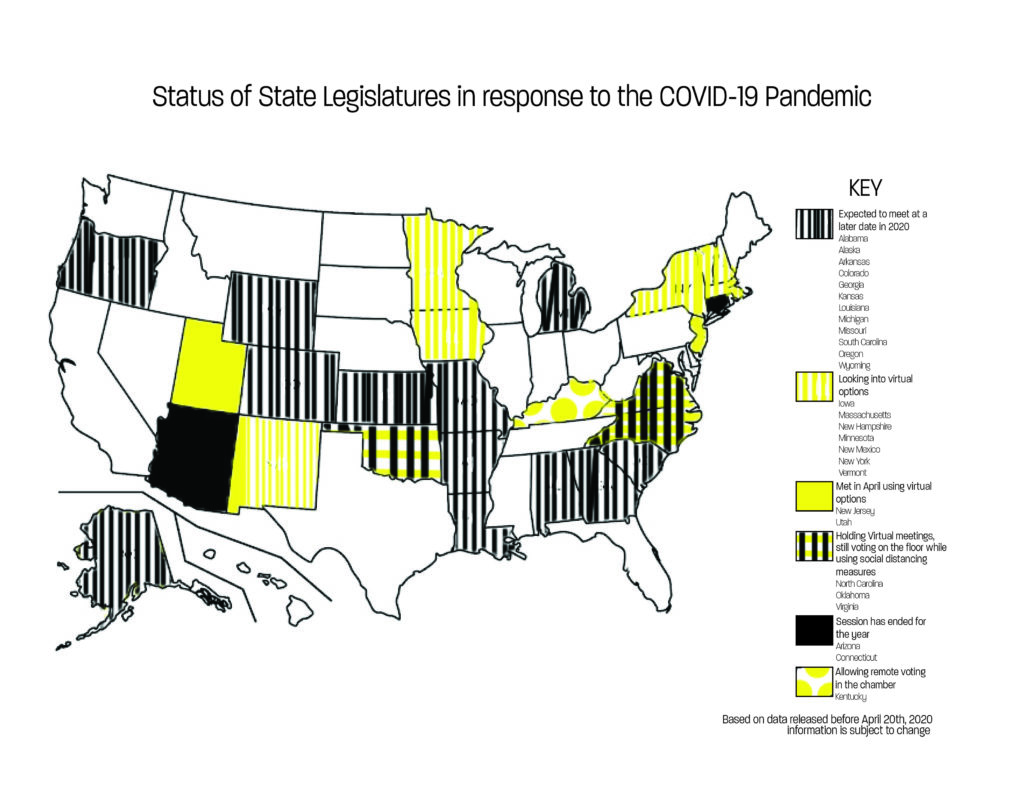

Many other states have claimed that this experience is nearly impossible to replicate and have taken drastic measures to continue to meet.

In Michigan, lawmakers continued to convene in the state capitol building earlier this month despite having a member of the Michigan House of Representatives pass away just a few days before from COVID-19. They laid black fabric over his desk and highlighted his name in white on the electronic roll call.

In Connecticut, the normal legislative session, which was set to end in early May, was prematurely cancelled. States such as Arizona and South Carolina have faced similar problems.

Utah joined just a few other states that have considered meeting remotely. New Hampshire and North Carolina will film remote committee meetings. Minnesota met in mid-April to determine rules surrounding a virtual legislative session. During the final days of Utah’s 2020 regular legislative session, lawmakers passed a joint rules resolution that allowed the legislature to conduct electronic sessions.

The Utah measure, SJR16, allows the session to move online under four different circumstances:

- If the governor declares a state of emergency.

- If the speaker and president decide that it is too dangerous to physically meet at the Capitol.

- If the president and speaker decide that a physical meeting at any location is too dangerous.

- If there’s some type of natural disaster, enemy attack, etc., that prevents at a minimum 25% of a body from attending its meetings, then the House speaker and the Senate president can allow that 25% or more to attend the meetings electronically.

A virtual chamber had yet to be set up when the bill passed, but the legislature had provided ways that would still allow the legislature to meet while complying with public meeting laws.

This was the first time the Utah Legislature had ever convened in an electronic virtual meeting. It was also the first time that the legislature used a Utah Constitutional that allows lawmakers to call themselves into special session. In 2018, voters approved a change to the Utah Constitution that allowed lawmakers to call themselves into a special session without permission from the governor.

State legislatures across the nation have battled with governors on how to handle the global pandemic.

In Kansas, The Legislative Coordinating Council met in mid-April in lieu of the full legislature. The council questioned a recent executive order made by Kansas Gov. Laura Kelly, who had released an executive order in mid-April that would limit religious gatherings to less than 10 people. The LCC claimed that this executive order was unconstitutional and infringed upon the rights and civil liberties of Kansas residents.

Kansas Attorney General Derek Schmidt said in a memo that “In (their) view, Kansas statute and the Kansas Constitution’s Bill of Rights each forbid the governor from criminalizing participation in worship gatherings by executive order.”

Each state’s contrasting decisions regarding legislative action during COVID-19 highlights the power of the legislature in each state. Their actions also acknowledge the existence of a more fundamental question about the balancing of power between the state legislature and the governor during a state of emergency.

This issue was specifically prevalent in Utah. Two new bills heard during the historic online session addressed the governor’s role and influence in Utah.

HB3005 would require that the governor provide notice and consultation with certain legislative branch officers before issuing a declaration of a state of emergency at least 48 hours in advance. The bill also prohibits the governor from suspending the enforcement or application of certain provisions.

Rep. Francis Gibson, R-Mapleton, sponsored the bill. “The governor has the ability to move more swiftly than the 75 and 29,” Gibson said. “I think there are instances where we need to be notified more than 20 minutes before a declaration comes out.” Gibson says that legislators have received notification as little as 15 minutes in advance before the governor has issued a declaration.

“It seems unnecessary, it seems like an overreach,” Rep. Merrill Nelson, R-Grantsville, said speaking against the bill. Nelson said the office of governor is designed to respond to emergencies in a swift and timely manner. He worries the legislative branch is “overstepping” and it may be a “violation of that separation of powers our constitution enshrines.”

Throughout the session, citizens were allowed to share public comments on the Utah Legislature website. In compliance with public meeting laws, the committees released the comments onto a publicly accessible document as they were released; however, only first names were used. Comments spewed in from across the state as Utah residents outwardly opposed the piece of legislation.

“I am strongly opposed to the legislature’s attempts to claim executive decision-making authority in relation to declaring a state of emergency and limiting the ability of elected officials to declare lockdown measures,” Richard, a Murray citizen, said on the public comment board. “There’s something about anyone giving themselves more power that shows that greed and self-interest are the motivators, rather than regard for constituents.”

Brenda, a Salt Lake City citizen, also spoke against the bill. “The governor has executive power in an emergency and does not need to consult the legislature,” Brenda said in a public comment. “Waiting 48 hours could put the state in danger. In an emergency, one person needs to be in charge. This is a power grab by the legislative leaders.”

Gibson said he isn’t trying to take away the role of governor. “We are saying we are an equal yolk here,” Gibson said. “Let’s work together. Let’s see if we can figure something out together.”

Once the bill was presented to the Senate, senators clarified that in the event of loss of life, there would be no notifications needed. In the cases of severe injury or loss of property, the governor would be able to make an executive decision. The governor would have to notify the legislature and consult with them 24 hours afterward, instead of the previously proposed 48 hours.

“People think that the legislature was somehow removing authority from the governor,” Gibson said when the bill returned to the House. “This could not be any further from the truth. This bill is meant to be a cooperation.”

Rep. Brady Brammer, R-Pleasant Grove, said, “We’re a part-time legislature, so 24 hours is more difficult to respond to. Forty-eight hours is more palpable for us.”

Rep. Val Peterson, R-Orem, did not favor the changes the Senate made. However, Peterson said, “Twenty-four hours is a lot more than 10 minutes,” regarding legislators being informed by the governor.

When the topic of separated powers was discussed on the House floor, Gibson said, “There is also weight from the executive branch that weighs down on us as well.”

For HB3005’s final passage, the House voted 66-9.

Another bill, SB3004, would create the Public Health and Economic Emergency Commission. It was heavily debated in the online House. The commission would advise and make recommendations directly to the governor regarding Utah’s response to the COVID-19 emergency.

Lauren Simpson, who currently serves as a policy director for Alliance for a Better Utah, said in a statement, “SB3004 is an example of a solution in search of a problem, and a legislative body that wants to expand its power. Not only is it an embarrassing power grab, the commission could duplicate and even undermine current response efforts already under way,”

Utah residents opposed the bill online. “It adds another layer of individuals who are not necessarily qualified to make these decisions,” Linda, a Salt Lake City citizen, said in a public comment. “Leave politics out of the public health emergency.”

Bill sponsor Sen. Daniel Hemmert, R-Orem, said that the commission is purely advisory and that the governor is the final decision maker. The governor also does not have to accept the commission’s recommendations as a whole.

The governor would be required to either accept the recommendation from the committee or explain why he is not accepting it. If the governor adopts a recommendation by order, that would supersede any local order that is more restrictive than the governor’s order. The governor signed SB3004 on April 17.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.