Six weeks after her first child was born, Kayla Geddes found herself sitting in her car crying.

“I realized that I couldn’t remember the last day that I hadn’t cried. I had cried so many days in a row, and that’s when I (realized) this isn’t normal,” Geddes said.

She reached out for help and felt a difference quickly after she started taking prescribed medication.

“I want to be a good mom, a good wife and a happy person, and for me, (the medication) is something that really helps,” Geddes said.

Geddes is not alone; it is common for mothers to develop symptoms of postpartum depression after childbirth. Some of the symptoms include anxiety, insomnia, irritability, worry and sadness typically seen in depression.

Geddes said she tries to be open about her experience to try to make it less taboo to talk about postpartum depression or medication. Although she knew what postpartum depression was, Geddes did not immediately realize she was dealing with it.

She said a postpartum visit focusing on mental health or someone talking to her and asking hard questions, like how she was feeling and whether she was overwhelmed, could have helped her realize what she was going through earlier.

During this time, Geddes started a podcast and tried to be involved in social media for promotion.

“Looking at these beautiful pictures of moms who appear to have it all together in every picture and they’re always having fun and their dinners are beautiful and their houses are clean and beautiful … I’m sure that played a part,” Geddes said.

She said she tries to be real on social media, acknowledging her struggles and that life is not perfect. She encouraged others to find a professional to speak with if they are suffering.

“Having kids is really hard but also really joyful, and it should not be something that moms feel like they have to suffer through,” Geddes said.

Amy-Rose White, a social worker and coordinator for the Utah chapter of Postpartum Support International, said the Postpartum Support International Utah social media pages are gaining hundreds of followers each month. More women are seeing positive messages and helpful information through social media.

“If we can put that out there in a way on social media that young women are being exposed to on a daily basis, then we’re more likely to also change those internalized notions of what it means to be ill and what it means to seek help,” White said.

“What happens when it’s not a bundle of joy?” — Brook Dorff

Brook Dorff, a maternal mental health specialist with the Utah Department of Health, said moms have a lot of pressure to be the “perfect Pinterest Mom,” and hear colloquialisms like “bundle of joy” or “pregnancy glow,” which can be detrimental when that’s not how they feel. She said the idea of perfectionism on social media gives the impression that no one else is struggling.

“The second that a mom doesn’t meet that expectation then it’s like a moral failure on her part, which is what society wants us to think. But it actually happens. It’s more common than we even talk about,” Dorff said.

Stigmas in the Utah religious culture

Dorff said one in five women in Utah experience perinatal mood disorders, similar to the national rate, but Utah also has the highest birth rate in the nation, which making the issue more prevalent. She said that between 8,000 and 9,000 women in Utah experience postpartum depression each year.

“In Utah, we have such a strong culture of wanting to just be the best. It doesn’t come from a bad place. I think it all started off really well intended … (but) it has turned into a silencing device where people don’t have the opportunity to actually talk about their struggles,” Dorff said.

She said things are changing, but not as quickly as they should. The “mom community” is plugged in and are great networkers, and Dorff said they can help improve the mindset by sharing their story on social media and with their friends.

White grew up outside of Utah and isn’t a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but said most of her clients are, and she sees an unusual culture of perfectionism.

“Any culture that emphasizes a woman’s identity through having children is automatically going to predispose a woman to expect, to want that, to enjoy that and to be good at it. That is a common expectation all mothers have anyway,” White said.

She said faith and Utah culture makes it difficult for some women to ask for help and admit they are struggling. White said less than half of women are screened nation-wide, and only 6-7% of those identified with postpartum depression will reach out for treatment. However, White said this has improved in the last two years.

Maleah Warner, mother of five living in American Fork, Utah, experienced postpartum depression after her fourth child was born. Looking back, she said she had symptoms after her second child, but just struggled through it until they went away. With her fourth child, it was different.

“I just felt broken. It felt like my go button was not working I felt like I was swimming through tar, every movement took so much effort.” — Maleah Warner

She thought she simply wasn’t coping with motherhood. She was telling herself to wake up earlier, be more organized, exercise and eat nutritiously and pray harder to get better.

“I really thought it was just my disorganization, and that wasn’t something I could talk to people at church about,” Warner said.

Warner attributed her symptoms originally to taking care of an infant and three other children. At her six-week check-up, she told the doctor she didn’t want to take an antidepressant for her symptoms and left feeling like she didn’t have any answers.

As it got worse, Warner waited for something physical to show up to explain her struggles.

“I just thought that it had to be something bigger because I felt so awful,” Warner said.

She said her body eventually shut down, and she started trying to heal naturally with supplements, yoga and acupuncture. It wasn’t until almost 18 months after the baby was born Warner came across a book which explained what depression looks like in the brain and she realized it was not something she could think her way out of.

“That understanding is what helped me to finally be able to take medication and realize that it was a physical issue not a character or personality flaw,” Warner said.

Warner said education is a powerful tool to overcome postpartum depression. She talked about educating doctors and pediatricians or giving information pamphlets to help women recognize what they are going through.

Always different

White said there is still ignorance about what postpartum depression actually looks like, and the term “postpartum depression” is a misnomer. She said women may meet the criteria for major depressive disorder, but they feel anxious, worried, irritable or angry more frequently than sad. She said about 25% of women experiencing postpartum depression will have intrusive thoughts often of harm coming to the baby at their own hands.

White said clinicians and medical providers need to be educated about the different symptoms because there is still misunderstanding even though postpartum depression is the most common complication of childbirth.

“If women are honest about what’s going on to their care provider, they are often in a precarious position because they might reveal something that the physician doesn’t recognize and (the physician) will either minimize it and dismiss it or they’ll make a bigger deal about it than actually needs to be made,” White said.

White said the national rate for postpartum depression is about to 21-22%. Further, 15-20% of moms will experience generalized anxiety disorder and 5-10% experience postpartum OCD.

“No one is talking about those,” White said.

Cami Jamison said she had researched postpartum depression early because her mom had it. She reached out to her doctor after she noticed the signs when her son was one month old. She said she wasn’t sad and mopey, but had major anxiety with panic attacks and didn’t feel connected to her baby or miss him when he was gone.

She said she had been cautious of medication but didn’t know what else to do, so she took the medication she was prescribed and felt better within four to six weeks.

“I didn’t tell most people, just because it seemed like a weakness. Motherhood is supposed to be this big important wonderful life goal and so for me to get there and feel like I didn’t like it … it made me miserable and sad, like that didn’t feel like something I should tell my Relief Society president,” Jamison said.

She said it would have been helpful if people knew she was anxious in the evening and didn’t want visitors or if she had ministering sisters she could ask for help.

“There are lots of ways to be helpful, but I couldn’t express to them what would be helpful because it seemed like not what I should be wanting,” Jamison said.

She said knowing that other people knew it could happen and having people acknowledge it more would have helped her realize it wasn’t “a big crazy thing.” She said she had friends who experienced it and didn’t get help or recognize it at the time.

“If more people talked about it and shored those experiences I feel like it would be easier to recognize,” Jamison said.

Transition to parenthood

Megan Rigdon said she didn’t realize she suffered from postpartum depression until she decided to specialize in perinatal mood disorders and took classes. Rigdon is a clinical social worker at Sunny Day Counseling in Springville.

“I think they have this idea in their mind of like what motherhood is going to be like, and then when you become a mom it’s so different,” Rigdon said.

She said there’s a process of adjusting expectations and realizing motherhood is not the Instagram picture and is hard and tiring and special in unexpected ways. She said there is often a fear around talking about postpartum depression. Women believe they could be seen as lazy or a bad mom. Sometimes, women dealing with intrusive thoughts are even scared child services would take the baby.

“There’s so much fear about it and so when you’re the person having those thoughts you don’t want to tell anyone but what you need to do is tell everyone to get the support,” Rigdon said.

Rigdon said the intrusive thoughts, which sometimes include thoughts of harming the baby, come from the protective section of the brain, not the aggression part.

She said she decided to specialize after having people call asking if she worked with postpartum depression and not having anywhere to refer them. She said a lot of women have told her they think they had postpartum depression after she tells them what she does.

Rigdon said figuring out how to get sleep is one of the main things a woman can do if she is struggling with postpartum depression.

“It will make a huge change when you’re trying to heal and recover,” Rigdon said.

Zachary Blackhurst, a clinical psychology graduate student at BYU, found in his research that if moms get more sleep they have “fewer depressive symptoms,” but lack of sleep doesn’t have the same consequences for dads. He said it is important to look at the entire family, and the partnership between the mom and dad.

“If dads get up more in the night to take care of the infant they can significantly improve the mother’s health,” Blackhurst said.

Postpartum depression in fathers

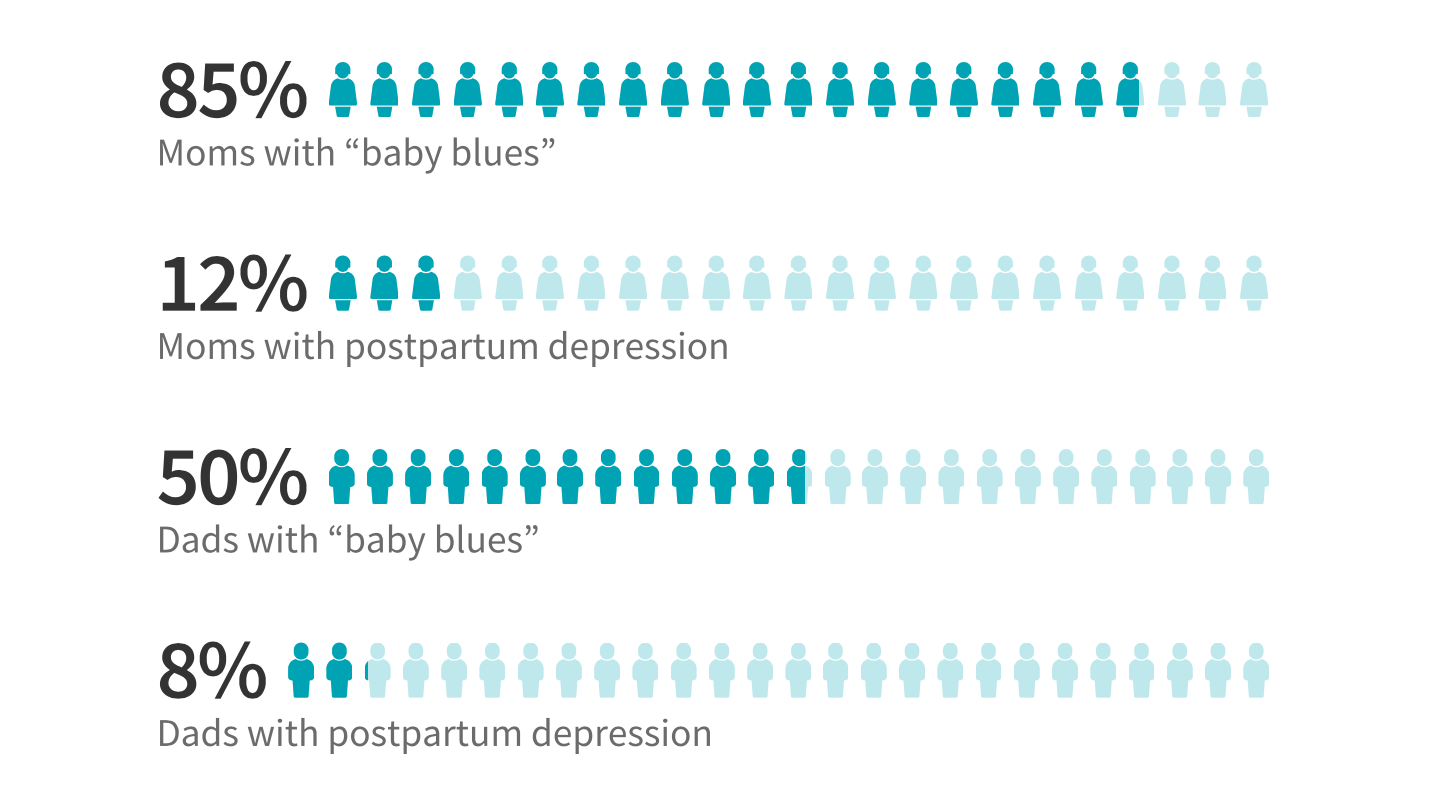

Although less sleep is not as much of a risk factor for dads, Blackhurst said about 8% of dads experience paternal postpardum depression, and about 50% experience the “baby blues.” He said we know less about dads’ experiences with postpartum depression, which has been overlooked in some research.

“Dads are trying to navigate their role in a changing family,” Blackhurst said. “In the majority of cases, mothers are taking on the lion’s share of the physical care of the infant, which can lead to the father feeling displaced, feeling helpless, worthless. … That kind of mindset has a negative impact on their mental health.”

Blackhurst is researching to determine the risk factors contributing to paternal postpartum depression. He said the risk factors with moms are often social and psychological including whether your partner is depressed and if they have social support.

“If we had a better understanding, then perhaps we could have more helpful interventions,” Blackhurst said.

The Emily Effect: Utah effort to share stories

Emily Cook Dyches was experiencing postpartum depression and died after experiencing a panic attack and running into oncoming traffic. Her husband, Eric Dyches, started The Emily Effect, an organization working to bring hope and awareness and end stigmas around postpartum depression.

“(The Dyches family) definitely could have kept that grief private and kept it to themselves, (but) the story is powerful and it has made a difference,” Warner said.

Warner joined the Emily Effect organization, and helps create their videos including one where she shares her story. She said the videos bring hope, showing women there are answers and treatments which will help them feel better.

Warner said that among the women she has interviewed for the videos, most have had something that triggers extreme worry and panic, where it feels like the moment is not safe and they need an escape. She said learning breathing techniques and positive mantras can help.

The Emily Effect was involved in working with the Utah Legislature to appropriate more money to postpartum depression support and has worked with Postpartum Support International to organize support hikes and other resources for women.

Utah government and Department of Health

The Utah Legislature appropriated $250,000 to the Department of Health to help with postpartum depression and perinatal mood disorders. Dorff said the money will be used in public awareness campaigns and to create an online database with Utah resources where women can find help. She said funds will also go towards telemental health services to help women from rural areas talk to trained professionals.

Dorff said suicide is the second leading cause of death for women in the perinatal time period, from pregnancy to a year after the birth, and it is something that needs to be addressed.

“If you can help treat a mother, you’re also helping her infant and her whole family unit. If you lose a mom you are affecting an infant and her whole family unit,” Dorff said.

The Utah Department of Health is also working with the Utah Women and Newborn Quality Collaborative to make sure women are screened for postpartum depression by doctors and OBGYNs. Dorff said this often hasn’t been happening, sometimes because providers realize it is a liability if they don’t know where to refer the women. The resource website will help with this issue as well.

“There’s a lot of momentum. Still, unfortunately, we have women in crisis and somehow we’re not reaching everyone,” Dorff said.

A disorder with hope

Although postpartum depression can be one of the hardest things a woman encounters, there is also hope. White said women who get the right treatment often feel markedly better within weeks or months and getting a healthy sleep pattern can help them improve in days.

“You’re not alone, you’re not to blame, and with help you will be well.” — Postpartum Support International motto.

“I tell women in my practice to expect a great improvement within weeks,” White said.

White said there is a lot of hope. Although women are more susceptible to complications during the perinatal time, they also respond to treatments better.

“You will completely recover,” White said.

Dorff agreed and said there are many resources available to help women.

“I think it’s just important to be aware that it can happen, that it’s not your fault and that you don’t have to be miserable and you don’t have to suffer alone,” Dorff said.