Elias Bobadilla is originally from Connecticut and was born to Peruvian parents. He has lived in Arizona, Colombia, and is now coming up on four years in Provo. One of his top priorities as a student is to represent people of color in all that he does as well as being someone that can help bring more minorities into BYU’s Marriott School of Business.

He studies accounting and will be graduating in April with a full-time job lined up as a financial analyst for Disney. However, despite all of his academic successes, he, like many other people of color at BYU, has often felt unincluded and isolated due to how hard it is to find people like him.

“I do still feel left out at BYU only because it’s hard and it’s not as easy for me to find my community. I have to go digging a bit and my friends of color are few and far in between because there are only a few and far in between at BYU,” Bobadilla said.

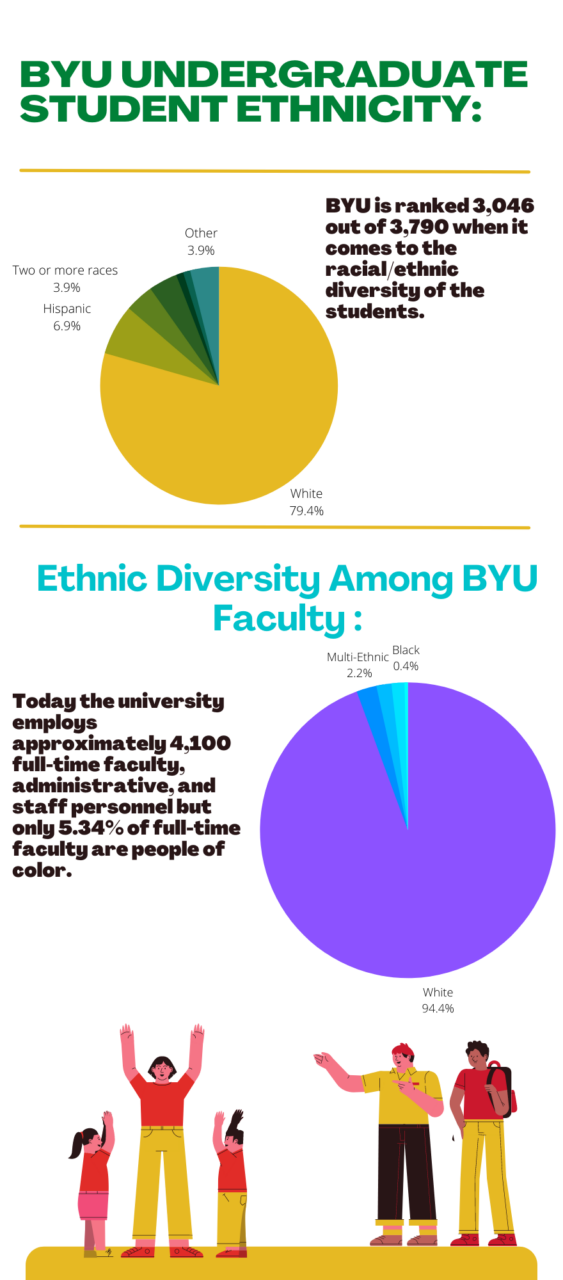

The majority of the student body and faculty at BYU is white which causes students of color to often experience discomfort and isolation.

Jane Lopez, professor of sociology and researcher of citizenship at BYU, touched on what she thinks the white majority struggles with the most to understand about people of color.

“They struggle to understand that people with different backgrounds experience BYU and BYU culture differently. There’s often an assumption that people’s college experiences are very similar, but that’s not the case at all,” Lopez said. “I can imagine that one thing that would make being a student at BYU really hard would be to have very little contact with people who look like you or have backgrounds similar to yours, especially people in leadership and authority positions.”

In June 2019, in a journal study entitled, “How Racial Stereotypes in Popular Media affect people — and what Hollywood can do to become more inclusive,” Nancy Wang Yuen, an American sociologist and professor at Biola University, examined how the absence of exposure to minorities can often lead people to rely on other sources to shape their perceptions of minorities.

“When there is a lack of contact between racial groups, people tend to rely on media stereotypes to formulate ideas about people outside of their own race,” Yuen said. Preconceived notions of people of color can be dangerous because they are often prejudiced towards them.

A 2012 study entitled, “Black Students’ classroom silence in predominantly White institutions of higher education,” Mahajoy A. Laufer, a child therapist that attended Smith College, examined how it is very common for white students, teachers and administrators in predominantly white institutions to ignore obvious mistreatment of minorities.

“Students of color perceived that white students rolled their eyes and sighed with exasperation when issues of race were broached and sensed that professors ignored racial microaggressions that occurred in their classes,” Laufer said.

The absence of exposure to people of color can cause minorities in classroom settings to encounter acts of microaggression, deal with ignorance and accept everyday marginalizing comments, Laufer said. It can be very normal for a student of color to encounter all of these every day.

Moises Aguirre, Director of Multicultural Student Services at BYU, has been a full-time faculty member for almost 10 years. In his job, he meets with many socioeconomically disadvantaged students who oftentimes are minorities. He shared what he believes might be the reason for racial tension on campus.

“I believe that it’s the lack of exposure. I believe that in Utah many of our students haven’t had the opportunity to interact with people of color making it very uncomfortable and at times making many mistakes, or comments, or behaviors that can be very hurtful for a person of color,” Aguirre said.

The discomfort and isolation that students of color feel at BYU forces them to find ways to adjust to living in a predominantly white area, and in various cases, students of color are faced with an internal conflict in which they have to decide on whether to be themselves or change to better fit in within a predominantly white community.

BYU history professor Ignacio Garcia is an expert in race and Latino history and has been a faculty member for over 20 years. He shared his opinion on how students have to give something up in order to call BYU home.

“It’s still a feeling among many students that this isn’t yet home, and if it is home, what did you give up to be able to build a home? In other words, for students of color, attending BYU is like buying a home,” Garcia said. “And like a home, it keeps costing you for a long time, because one of the things that happens is that sometimes you have to adapt, but it’s the kind of adaptation in which after a while you’re not sure who you are.”

For students of color, wanting to feel accepted can come with the social pressures from the environment that they are in. It can present many dangers, such as feelings of embarrassment and shame for who and what they are.

Garcia listed some of the most common ways in which students of color adapt to BYU.

“You avoid difficult issues, you never bring them up, you downplay and you end up being the first line of defense for those who might be insensitive because you want to protect their feelings,” Garcia said.

For a student of color, adjusting to being a part of BYU can involve changing every aspect of their lives.

Garcia thinks that at BYU, people of color are faced with making big changes in their lives in contrast to their white peers around them who are among a white majority in which they feel comfortable and don’t see how a person of color could encounter different struggles or have different experiences from theirs.

“That idea that you are legitimate in your differences is sometimes the hardest thing to accept for a person that is not of color,” Garcia said.

Aguirre said there seems to be a dangerous notion among students and faculty at BYU that frequently comes to question. It is hard for many to simply accept and understand that people of color have their own troubles and difficulties and instead it becomes a competition to see who has it worse rather than seeking to understand one another, he said.

“It’s not about I also had it hard but to recognize that my story is very unique and it is my own and nobody else has gone through that and nobody else can fully understand how it is to experience what I experienced,” Aguirre said.

Seeking to understand each other’s backgrounds and understanding that people of color have valid experiences is extremely important to bettering the treatment of minorities at BYU. The end goal should be for everyone at BYU to come together in an effort to be welcoming and supportive in an attempt to build Zion, Aguirre said.

“That concept of being one in mind and heart. It doesn’t mean that we all need to be the same in thinking but that we can all have the same purpose and I think that BYU is working towards that,” Aguirre said.

When asked what needs to be done right now to help improve how minorities feel on campus Garcia suggested these three strategies: first is people have to talk about racism. Second, people should ask those who are impacted and third, people have to decide that they need a new direction.

“A truly Zion university that takes all of God’s children together is not the university that we have now. Our priorities, where we put our money, how we develop our courses, how we define what our students will be doing when they graduate, how we apply our politics, all of that will have to change because otherwise, all that you’re doing is forcing people into your system,” Garcia said.