BYU psychology major Bella Lunt spent years trapped in a restrictive relationship. It gave her a lot of anxiety and she struggled to find a healthy solution. Ending the relationship wasn’t an option, because she couldn’t live without it.

Her toxic relationship was with food. “I was attempting to recover from an eating disorder, but still had extremely disordered eating,” she said.

Corinne Hannan, a clinical psychologist at BYU Counseling and Psychological Services, has seen firsthand how eating disorders affect women like Lunt. Hannan developed a course, listed under Student Development 141R, to help prevent them called Eating, Culture and Body Image. It has helped numerous students—including Lunt—improve their relationships with food and their bodies.

Before the class

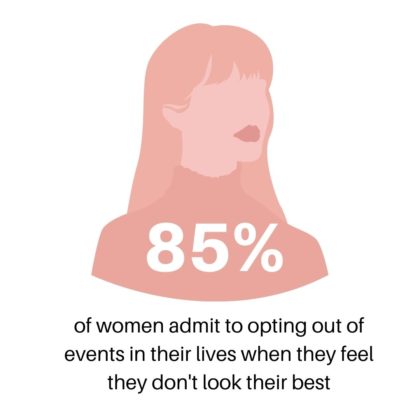

One of its first students was Janae Smith, a senior in communications studies. Smith grew up dancing in Florida, where everyone on her team looked different and her coach could care less whether her dancers were “skinny” or not. Her body-image issues began when she started college and magnified when she returned home from her mission.

“I felt like I had to be a certain size to be able to date,” Smith said. She felt she did not match the stereotypical Provo “look.”

Smith was also struggling with an undiagnosed illness, and she said she got sucked into a wellness culture that told her she could cure her body if she ate a certain way or took supplements. Her illness didn’t budge.

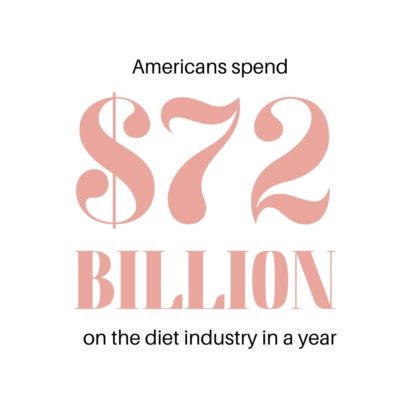

“People were just making money off of me being sick,” she said.

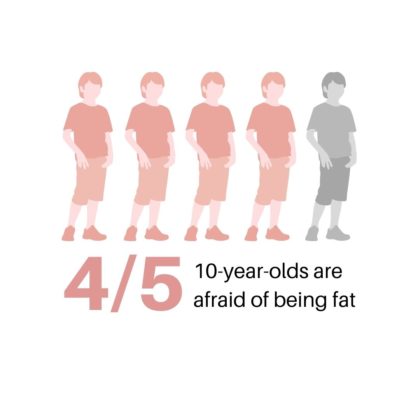

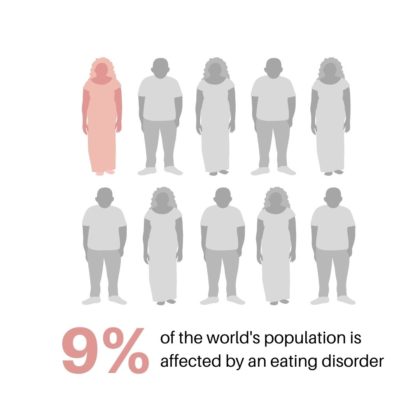

Christine Renfro could list many more stories. She has worked as a family nurse practitioner on college campuses for the past 20 years, and she said she has seen teenagers obsess over their weight and young girls become osteoporotic from eating disorders.

Navigating a toxic sea

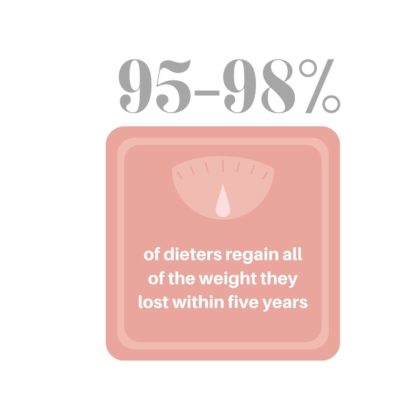

Dietitian and activist Christy Harrison attributes situations such as these to diet culture, which she defines as “a system of beliefs that equates thinness with health and even moral virtue.”

Hannan described diet culture as a toxic sea of misinformation in which everyone swims, and she said it saddens her.

“It’s like I work in a lung cancer ward and people are having their lung masses cut out, then I go into the world and see everybody smoking,” she said. “If you’re working in a lung cancer unit, you’re going to see smoking very differently. I work on the front lines with eating disorders every day.”

Her attempt to help people navigate the sea of diet culture took form in her new class. As its name suggests, the class covers the dangers of diet culture, principles of intuitive eating, and tools to improve body image. Class materials included Harrison’s book “Anti-Diet,” abstracts from reputable studies, and documentaries addressing the problems within the diet and beauty industries.

She said she has witnessed many students’ and clients’ lives “gorgeously heal and transform” as they overcome disordered eating and negative body image.

Student experiences

Smith signed up for the first class while still steeped in the pressure to be skinny because she needed two extra credits, and the mention of body image intrigued her. She said the course opened up a new world for her — one where she didn’t have to feel bad about her body.

“I wish that everybody knew how stupid and twisted and manipulative diet culture is,” she said after taking the class. “Anybody trying to tell you to change your body or sell you a product—they just want your money from you. They just want your money.”

She said she has heard many people say they wish the class was required, including Lunt.

“If we collectively as a campus stopped focusing on bodies and instead focused on the things we are doing, that would be awesome,” Smith said.

Lunt said she signed up for the class because she also thought she could use a class talking about body image, but intuitive eating was a foreign concept. She said she thought it would teach her how to diet.

It did the opposite.

“I hated food and was scared of it before taking this class, but have learned how essential loving food and creating a good relationship with it is,” Lunt said.

Renfro has seen similar (albeit more extreme) transformations in her work. She said when her patients enter recovery, they are better off physically, mentally and emotionally. They’re happy.

“When they’re done, they’re just so relieved that they don’t have to devote that kind of energy to an eating disorder,” she said.

Addressing skepticism

Hannan said the material is personal, provocative and sometimes destabilizing for people, but she is basing it on thousands of hours of her own clinical experience and decades of research from other scientists.

She invited anyone who struggled with the material to ask themselves two questions. First, how would they know if they were wrong? Second, do they want to know?

She said she asks herself those questions every day and has moved away from her past beliefs about food and body in that way.

The material challenged Lunt’s beliefs, but she said it was for the best. She feels she has the right tools to be able to work through her body image issues, and she knows what she would say if she could give her old self a message.

“Society is trying to tell you that your body is an ornament meant to be meticulously polished and flaunted,” she said. “Your body is so much more than that. It is a vessel that carries a beautiful mind and an incredible spirit. Your body shape is definitely the least interesting thing about you.”