One of the worldwide impacts of COVID-19 has been a re-emphasis on individuals’ physical health. But that’s not new for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who follow the Church’s health code.

But attitudes around what is and isn’t healthy have changed. In recent years, BYU has seen a dramatic shift in long-standing cultural norms around the consumption of caffeinated beverages on campus.

Conflicting opinions

Elder Vaughn G. Featherstone, then a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy, spoke in General Conference in April 1975. His talk focused on the importance of cleansing body and spirit.

In a conversation with a bishop, Elder Featherstone recalled being asked about the Church’s stance on cola drinks. He told the bishop that the “Church advises against them” because of their “addictive substances.” The bishop still didn’t agree, noting that the Church handbooks didn’t mention cola.

“Well, I guess you will have to come to your own grips with that,” Featherstone said. “But to me, there is no question. You see, there can’t be the slightest particle of rebellion, and in him there is.”

Fast forward to President Dieter F. Uchtdorf’s talk in October 2016. When he was younger, President Uchtdorf had to spend a lot of time learning to use a computer.

“It took a great deal of time, repetition, patience; no small amount of hope and faith; lots of reassurance from my wife; and many liters of a diet soda that shall remain nameless,” he said.

While Uchtdorf didn’t name the soda directly, most members inferred that it was a caffeinated drink.

The Church has never taken an official position for or against caffeine, leaving the decision about whether to consume it to its members. The Church newsroom even clarified in 2012 that the Word of Wisdom does not say anything about caffeine.

The debate that sometimes occurs over this issue comes from different understandings of the Word of Wisdom.

Because restricted drinks (such as coffee and tea) sometimes contain caffeine, some members think caffeine is the primary reason these drinks are not allowed. This understanding, combined with different Church leaders’ opinions, has led to confusion among members about what they’re “allowed” to drink. This was further emphasized by the lack of caffeine available on BYU campus until three years ago.

Some members think that because caffeine can be addictive and may alter health in a negative way, it should be included as a harmful substance to the body. In the March 1990 Ensign, Dr. Clifford Stratton, a doctor of human anatomy at the University of Nevada, mentioned potential health consequences that come from caffeine intake.

“After twenty years of experience in medicine, I counsel inquiring members that eating or drinking anything that may result in bodily harm is probably a violation of the spirit of wisdom enjoined in Doctrine and Covenants 89,” Stratton said.

Leaving it up to the individual

Church members like Kellie Creager choose not to drink caffeine because they don’t like the way it makes them feel.

“I feel a slight buzz sometimes, and I don’t like that feeling,” Creager said. “It increases my heart-rate and affects my sleep. It’s been many years since I have had a caffeinated drink.”

Other members like caffeinated drinks. Jai Knighton, a BYU alumnus who graduated in exercise science, takes energy supplements before he works out.

“The supplement helps me exercise for longer and at a higher intensity,” Knighton said. “When I exercise without one, I feel tired and beat.”

The energy supplement Knighton takes has around 250 milligrams of caffeine per serving. When asked about caffeinated drinks, he said he enjoys the occasional Dr. Pepper but doesn’t drink soda very often.

“The high sugar content in soda should be a higher concern than the amount of caffeine the drink has,” Knighton said.

BYU alumnus Brent Friess also views the sugar content of soda as a huge detriment to health, though he also believes caffeine isn’t doing the body any favors.

“If the Word of Wisdom is viewed as a code of health, and thus means we should do and choose what is most healthy for our bodies, then the data would show that we should not drink soda at all whether it contains caffeine or not,” Friess said.

Friess said he thinks members of the Church are trying to become more like Christ, and taking better care of the body is one of the ways people can improve themselves over time.

“I see very little difference in healthy lifestyle of a person drinking a cup of coffee, versus that same person drinking a 44-ounce Coke,” Friess said. “Yes, one is ‘obeying’ the Word of Wisdom while the other is not, but neither is making a smart health choice.”

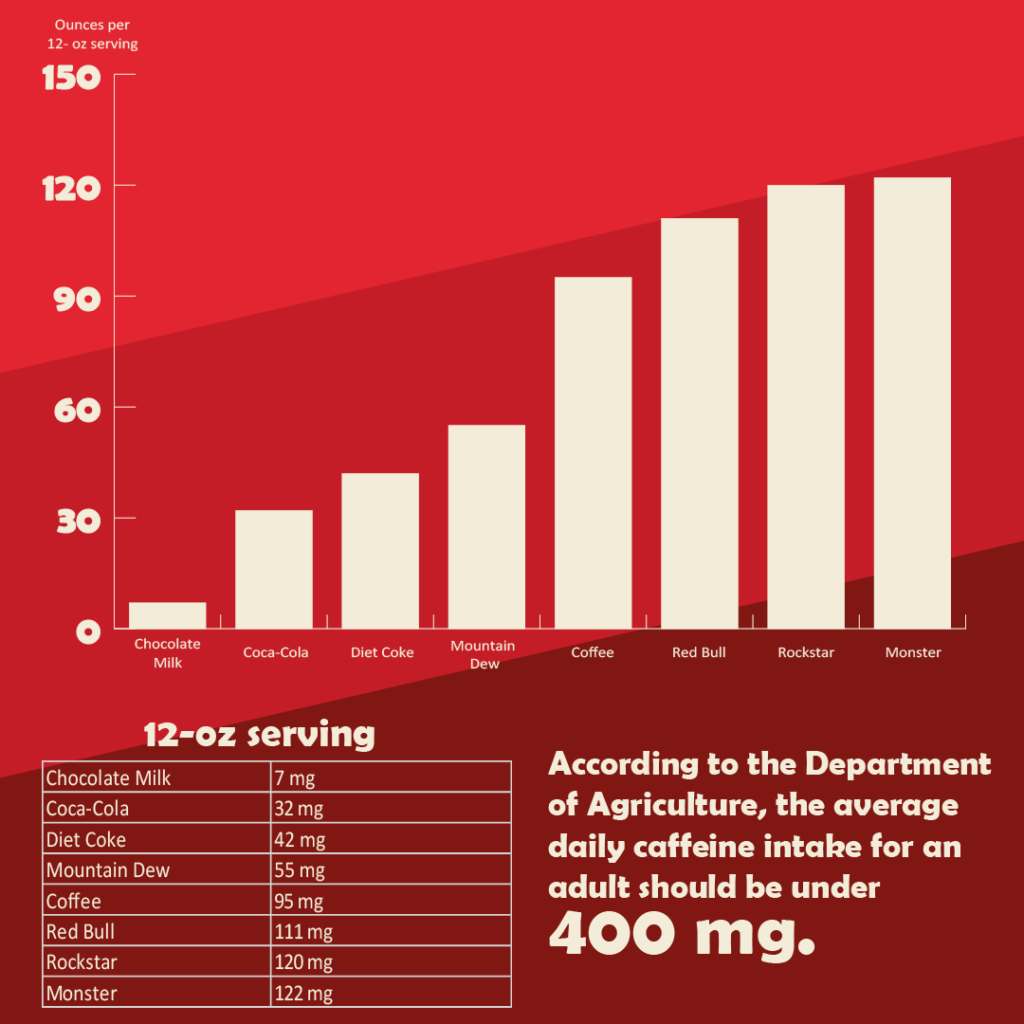

According to the Food and Drug Association and Department of Agriculture, the average caffeine intake an individual can have daily (while remaining healthy) is 400 mg. This is around four cups of coffee or 10 cans of Diet Coke per day.

An intake higher than 400 mg. can lead to unpleasant side effects, such as insomnia, anxiousness, heartburn, faster heart rate, upset stomach, nausea, headaches and jitters. The FDA estimated an intake of 1,200 mg. could lead to toxic effects like seizures.

Though there is evidence that consuming excessive amounts of caffeine can have negative effects, research performed at Harvard shows that smaller doses of caffeine may actually benefit people’s health.

Harvard researchers acknowledged the importance of monitoring personal intake but noted that caffeine can be used to regulate breathing, help with exercise and potentially protect against dementia. For those without heart problems, Harvard professor and researcher Stephen Juraschek said the 400 mg. limit is a good place to stay.

“This amount is considered safe and isn’t linked to any long-term effect on blood pressure or heart attack or stroke risk,” Juraschek said.