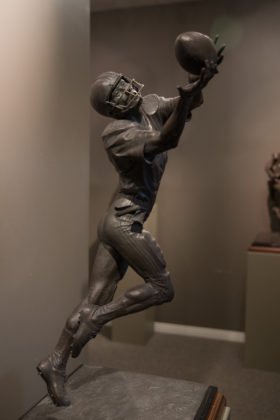

People going past Buswell Bronze in Pleasant Grove, Utah, likely don’t know it’s there. The business is set away from the main part of town, just one nondescript warehouse in a cluster of others. Yet it’s here that Blair Buswell — a former BYU football player and current professional sculptor — practices his craft, creating official Pro Football Hall of Fame busts, larger-than-life wagon trains and other western art and even busts of Church presidents for the Conference Center.

“I love the human figure and trying to capture the … gestures and expressions,” Buswell said.

And though Buswell’s road to becoming an artist began well before his time at BYU, it was at BYU he combined his love of sports and art into a professional sculpting career of now nearly 40 years.

An affinity for art

Buswell said he grew up in North Ogden and gained an affinity for art early on when his mother would give him clay in Sacrament meeting to keep him quiet. He would make his own toys out of it, but did not realize until junior high “that people actually made a living at what I (did) for fun.”

From junior high on, he wanted to be an artist, though he continued being an athlete as well. While attending Weber High School, he was both art Sterling Scholar and All-State in football and track.

He went on to attend Ricks College on art, academic and athletic scholarships, where he played football and ran track. His art teachers thought he spent too much time playing sports, and his coaches wondered why he spent time on art.

Buswell said he discovered illustration and design at Ricks College and loved it, but knew sculpture was what he wanted to do with his life. He briefly transferred to Utah State University for their spring football program before leaving to serve a mission in Washington, D.C.

Buswell also found ways to sculpt while serving his mission. One day after church, a member, who was also a high school art teacher, told him and his companion she had something in her car for them. Thinking it was cake or cookies, they salivated as she opened the trunk — revealing 50 pounds of clay.

“I was super excited,” Buswell said. “My companion wasn’t.”

He stayed up all night sculpting, and the following day, received permission from his mission president to sculpt during special firesides, during which he would go through many of the missionary discussions while working on a sculpture. After about an hour, he would have a finished head of Christ.

Following his mission, Buswell had the same offer to walk-on at Utah State that he had for BYU. He could have stayed at Utah State and continued concentrating on illustration, but he said BYU was the only school in the Intermountain West with a traditional figurative sculpture professor.

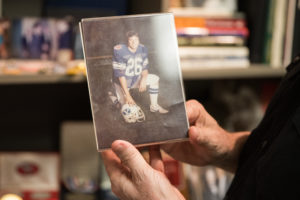

Buswell ultimately redshirted at BYU and played on an art scholarship between 1979 and 1981 as a reserve running back. He said BYU’s team doctor saw his art and thought he was crazy for risking his hands playing football, even making him special hand pads and checking him before games to make sure his hands were protected. Though he “didn’t get in much,” he said he played with some great quarterbacks, including Marc Wilson, Jim McMahon, Steve Young and Robbie Bosco.

Buswell’s big break came during his senior year at BYU at an end-of-year awards banquet where he was honored for work he had done outside of football and where he displayed some of his sculptures.

The guest speaker that night, Buswell said, was then-San Francisco 49ers Coach Bill Walsh, who had just won his first Superbowl with the team. Walsh took notice of Buswell’s work and asked Buswell to do a sculpture of Walsh and then-San Francisco 49ers owner Edward J. DeBartolo, Jr.

“So of course, I jumped on that,” Buswell said.

Buswell flew to San Francisco, where Walsh and DeBartolo posed for Buswell the day before the first pre-season game. When he finished the sculpture, Buswell flew to DeBartolo’s home in Youngstown, Ohio, to give him the sculpture.

Buswell said DeBartolo was “really excited” by the piece and asked what his plans with sculpture were. Buswell said his dream was to work for the NFL, especially the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Smiling, DeBartolo picked up the phone, called the director of the Pro Football Hall of Fame and said, “There’s a young man here you need to meet. I’ll send him right over.”

The Pro Football Hall of Fame ultimately hired Buswell, and he has now sculpted for them for nearly 40 years. In 1990, he was the first sculptor to be named Sport Artist of the Year, and in 2008, he received BYU’s Distinguished Service Award.

“It’s kind of like in sports,” Buswell said. “When you’re called on, you’ve got to be ready to do your thing.”

Ben Whiteside, owner of the Red Piano Art Gallery in South Carolina where some of Buswell’s work is sold, said Buswell is “one of the leading figurative sculptors of his generation.”

He also said Buswell is an artist that should be considered if a person wants quality work, and called him the “go-to guy” for sports sculpture.

Still pinching himself

Buswell said he doesn’t know if there’s been a single greatest highlight of his career, but said sculpting has allowed him to go places he never thought he would and meet people he never dreamed of meeting, such as athletes Mickey Mantle, Oscar Robertson, Jack Nicklaus and Merlin Olsen.

He’s also sculpted a Catholic archbishop, a Baptist preacher and busts of three prophets: President Harold B. Lee, President Thomas S. Monson and President Russell M. Nelson, the last of which is still in progress and will be added to the Conference Center this fall.

“I’ve been pinching myself for a lot of years,” he said.

Additionally, he said his family has been supportive of his career as an artist. For example, the summer after he came home from his mission, his father gave him a list of possible summer jobs, such as working at a grocery store or a gas station. Instead, he asked if he could convert half the garage into a sculpting studio. He and his parents changed the garage lights and stacked apple crates to make tables, “and I’ve never looked back,” Buswell said.

However, he said his career has been tough to balance with family life due to his sculpting deadlines. His wife is a flight attendant, so he’s also been “Mr. Mom” to his three kids, the youngest of whom is now a senior in high school.

Buswell said the best part of sculpting is the tactile part of creating three dimensions.

“We joke as sculptors (that) a painter just has to pick an angle view and make it look great. We have to make ours look great all the way around,” he said.

He also said he wants people to feel emotion when they look at his work. When he’s sculpting people, he’s “trying to capture the personality, the feeling of that person.”

Buswell said he’s been waiting 30 years for the opportunity to sculpt his coach, LaVell Edwards. Another future goal is doing a piece for the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington, D.C.

And to anyone hoping to make a living as an artist themselves, “Good luck,” Buswell said, “It’s a tough thing to get into.”

However, he added people should make art because they enjoy it.

“It’s the same thing with sports. How many people actually make a living playing football?” he said. “Do (art) as long as you can and have fun doing it. Enjoy the ride. You’re not a failure if you don’t become a Hall of Fame football (player) or a concert pianist or a famous artist.”