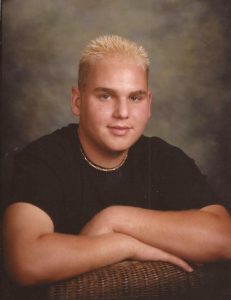

Tennyson Cecchini had gone from playing hockey and studying at Weber State University to living in his parents’ basement, addicted to heroin, by age 33.

Cecchini lost his house, his car and his child to his addiction. On May 12, 2015, he died on the bathroom floor as his mother tried frantically to revive him.

It all started with prescribed pain medication Cecchini began taking after he injured his shoulder playing hockey.

Every week six Utahns, like Cecchini, die from an opioid overdose, according to opidemic.org.

Three bills created by the Utah Legislature to combat opioid addiction and overdose deaths were signed into law in March and are beginning to create change in Utah’s opioid problem.

HB286: Essential Treatment and Intervention Act

HB286 allows a family member to intervene on an opioid-addicted individual’s behalf and petition for court-ordered intervention and treatment.

According to the bill’s text, spouses, parents, grandparents, stepparents, children and siblings can now file a petition.

Rep. LaVar Christensen, R-Salt Lake, the bill’s sponsor, said the bill specifically allows caring relatives to obtain the legal standing to petition for essential care and intervention for addicted loved ones.

Sen. Stuart Adams, R-Davis, the bill’s floor sponsor, said the law allows family members to intervene in a very thoughtful and rigorous way.

“It’s a very difficult issue,” he said. “We don’t want to take away anyone’s rights, but we also acknowledge where there’s clear evidence of addiction that there probably needs to be some intervening help if it’s possible.”

Christensen said part of writing the new law was taking care not to trample on individual rights. He also wanted to make sure the process wouldn’t make the opioid addict a criminal.

“It can’t be used as a criminal admission,” he said. “It can’t be used to convict you of a crime. It’s confidential.”

Christensen said the bill also includes a 72-hour emergency provision.

“If somebody is at risk of immediate harm or injury, you can go into court and you can get an emergency order,” he said.

The emergency order allows for a hearing to be held within 72 hours.

“They’re not going to wait around and find out that someone died just because they couldn’t get to court fast enough,” Christensen said.

The normal non-emergency process, he said, could take a month or two.

Christensen said one weakness in the bill is families have to be able to pay for the sometimes-expensive treatment ordered by the courts. He said he hopes to do more in the future to help families pay for treatment.

Christensen is currently working with government agencies, who are responsible for implementation, to create rules to help achieve the intended outcome. He worked with his constituents, and Tennyson’s parents, Celeste and Dennis Cecchini, to create the new law after their son, Tennyson, died from an opioid overdose.

Tennyson was 23 when he was injured playing hockey and prescribed a pain killer. At the time, he was managing an Alpine Home Medical supply store and lived off campus at Weber State. His parents didn’t know it, but he soon became addicted to opioids. Tennyson’s addiction started with pills but then, because it was cheaper, he turned to heroin.

“We didn’t know about it until the last two years of his life because he was an adult,” Dennis said.

While an adolescent’s addiction treatment can be managed by their parents, an adult addict is left to fend for himself, Dennis said. This makes it difficult to get treatment, he said, because the addiction hijacks the brain.

“They cannot make accurate decisions about how to save their lives,” Dennis said.

Tennyson moved in with his parents, having lost his house, car and child. As soon as his parents knew he was addicted to pills, they got him into an outpatient program. Dennis said his son was making decisions about his own treatment, which was the problem.

“Allowing a substance-use sufferer who is an adult to dictate the care is the most ridiculous thing we do in this country,” he said. “It’s asking for them to die.”

Dennis said Tennyson was in the outpatient program for two years. He and his wife found out their son was also using heroin from a worried counselor who broke the law to tell them Tennyson might overdose.

The Cecchinis found another treatment center for Tennyson, and soon after admission he was told he could go home after 60 days.

“No one gets better in 60 days,” Cecchini said. “Trust me. It takes much more time than that.”

Tragically, Tennyson died in the Cecchinis’ bathroom not long after his release.

After working through the shock of their son’s sudden death, the Cecchinis tried to assess what had caused their son’s death. Dennis retired early to work full time on understanding opioids and advocating for addiction victims.

The Cecchinis worked with Christensen in 2016 to pass HB375: Prescription Drug Abuse Amendments, which “requires prescribers and dispensers to use the controlled substance database to determine whether a patient may be abusing opioids,” according to the bill’s text.

Cecchini is helping with the implementation of HB286.

“It won’t bring Tenny back,” he said. “But hopefully what it will do is help other people not lose their children.”

Cecchini said HB286 is a major step forward.

For more of the Cecchini family’s story, listen to this podcast.

HB175: Opioid Abuse Prevention and Treatment

HB175 requires licensed controlled substance prescribers to undergo training within the next three license renewal cycles.

Controlled substances refers to hypnotic depressants, psychostimulants and opioids, according to the bill’s text. The training mentioned in the bill is the Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment method.

The Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment approach helps doctors spot the signs of a controlled substance problem and know what to do about it, said Rep. Steve Eliason, R-Salt Lake, the bill’s sponsor.

The “screening” refers to looking for signs and having a patient fill out a questionnaire about controlled substance use. The “brief intervention” includes the steps a prescriber could take to help the patient immediately, such as prescribing an alternative to an opioid or prescribing buprenorphine, a medication commonly used to treat opioid addiction. Buprenorphine helps wean patients off opioids, Eliason said. The “referral to treatment” part of the method includes recommending a patient see someone in addiction medicine.

“By requiring all these people to have it, we are training all prescribers — albeit in a very limited way — to be the frontline soldiers in the war against substance abuse,” Eliason said.

One concern legislators had about the bill was doctors’ busy schedules. Some, Eliason said, have to see up to four patients in an hour, making it difficult for doctors to take the time to go through the Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment process with a patient.

The bill requires Medicaid and the Public Employees’ Benefit and Insurance Program to reimburse doctors for taking the time to go through the process, Eliason said.

Doctors are not required to use the process, but Eliason said making it billable provides an extra incentive to do so.

“I just tried to create the educational training opportunities and incentives, in terms of reimbursement, for physicians to utilize it,” he said.

Eliason said the official state training has not been finalized yet, and he purposefully gave physicians several renewal cycles to get the training. He said it takes a while to get the word out about changes in training like this.

Eliason said he got the idea for the bill from Dr. Glen Hanson, a University of Utah professor and former director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse. He asked Hanson what the most impactful policy would be for controlled substances, and Hanson’s answer became the text of the bill. It was the only opioid-related bill passed by every committee and both chambers of the legislature unanimously.

HB50: Opioid Prescribing Regulations

Six times more opioids were dispensed per resident in the highest-prescribing counties in the U.S. than the lowest-prescribing counties in the U.S. in 2015, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

HB50 was written with the intent to change doctors’ opioid prescribing habits. It limits the number of days an opiate can be prescribed for a patient, said Sen. Evan Vickers, R-Beaver, the bill’s floor sponsor.

“If it’s an acute situation, which means short term, then the first prescription should only be written for a seven day supply or less,” said Vickers.

Vickers said after the first-time prescription of seven days, a doctor can determine what the patient needs from there. He also said a chronic situation is different and left up to the doctor.

Vickers, who is a pharmacist, said he sees the problem with opioids every day. He said it is important for pharmacists to counsel with physicians about dangerous drug combinations and to counsel with patients about their opioid use.

Rep. Raymond Ward, R-Davis, the bill’s sponsor, said prevention is an important part of fighting the opidemic.

“In the long run, it’s better to prevent than it is to damage people first and then try to help them afterwards,” he said.

Ward said the law has no enforcement mechanism or penalty accompanying it. He also said the law will likely take two years to take full effect, since doctors will hear about it gradually over time.

ABOUT OPIOIDS

In the past few months, opioids have taken center stage in news stories, television ads and billboards along I-15. The effort to alert Utahns about the state-wide “opidemic” has been headed by the Stop the Opidemic campaign.

According to the campaign’s website, opioids are extremely addictive narcotics often prescribed for pain. These include common medications like oxycodone and morphine.

Ward is a primary care physician who said he is closer than the average person to the problem. He said almost all the addicts he has talked to got addicted because a physician who prescribed a narcotic did not inform them of the addiction risk associated with their medication.

Eric Schmidt, CEO of New Roads Behavioral Health, a treatment center in Cottonwood Heights, said he has seen addiction start in other ways as well.

“What I consistently hear from people is ‘I started with a pill’,” Schmidt said.

He said peers can often get their friends hooked with a prescription pill they get from their parents’ medicine cabinet, he said.

Opioids reduce pain and cause euphoria, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. As individuals use them, their brains develop a tolerance for the drug, which creates a need for more and more of it to create the same effect, according to Stop the Opidemic. This can lead to addiction and dependency, which can result in overdose and death.

Ward said once someone is addicted, the withdrawal is horrible. He said addicts in withdrawal experience things like anxiety, the inability to sleep, the feeling of their skin crawling and swelling.

“They know that if only they can get another dose, they’ll feel better,” he said. “And they’re right.”

Ward said an addict will do whatever they can to get their fix, whether that means getting more pills from their doctor, going to a different doctor for more pills, or turning to cheaper options like heroin.

“If you look at the overdose deaths — people who die from overdoses — about half of them overdose from the prescription pills, and about half overdose from heroin or other illegal street narcotics,” Ward said.

Schmidt said it can be hard to understand what exactly causes people to turn to opioids, especially in a predominantly LDS state like Utah.

He said there isn’t as much stigma around a pill like there is around tobacco or alcohol. Schmidt said people report it relieves stress, anxiety and self criticism — although the opioid really only masks these issues.

He said the LDS Church is taking the issue very seriously.

“They’re not denying it, and they’ve devoted conferences to this topic,” he said.

BYU health science professor Gordon Lindsay said it’s possible LDS people are very caring, willing to share and frugal, so they share medication. He said LDS people are also very trusting of their doctors, and doctors are trusting of their patients.

Lindsay said education about the opioid epidemic is important, but legislation like the laws passed in March is a powerful part of the equation as well.

“We — the patients — are at fault, the pharmaceutical companies are at fault, the doctors are at fault,” he said. “As we pass these pieces of legislation, I do think it creates awareness saying, ‘Okay. This is a big deal.'”

MOVING FORWARD

Schmidt said the next step in fighting the opidemic is to improve the quality of addiction treatment. Families often can’t find information on the quality of treatment on treatment centers’ websites, he said, and current efforts to put quality ratings on treatment center websites are helpful for families looking for good treatment options.

He said there needs to be a change in drug education.

“Somehow there needs to be the same level of messaging around pills as there is around alcohol and pot and other illicit drugs,” he said.

Lindsay said integrating prescription data between states would be a great step forward, along with a system to notify a relative that a loved one is shopping around for drugs. He would also like to see easy and accessible drop-off locations for unneeded medication and putting more funding into drug courts.

Dennis Cecchini’s next fight, he said, is insurance coverage for addiction treatment.

“Insurance has to change so that they cover (treatment),” he said. “People cannot be kept out of treatment because they don’t have the money. That’s crazy.”

Dennis said one thing he and his wife wish they had known about for their son was naloxone.

According to Stop the Opidemic’s website, naloxone is a prescription medication that can reverse an opioid overdose. It wakes a person up from an overdose after it is injected in a muscle or sprayed in the nose.

Lindsay said the opioid issue is worth BYU students’ attention.

“We want to ‘enter to learn and go forth to serve,'” he said.

Since Latter-day Saints provide voluntary church service, he said, BYU students need to be equipped to serve people affected by this issue.

“We are here to be as the Savior’s hands and to lift and heal and do good,” he said.