Health workers say Ebola-related deaths could rise exponentially, numbering in the millions in just a few months, but researchers at BYU are determined to not let that happen.

Public health faculty and students, through a partnership with Cape Town, South Africa, have developed an effective method to prevent the spread of infectious diseases like Ebola, and they’ve been working on it for years.

One BYU participant is Gene Cole — a former project manager for the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the U.S. Agency for International Development. He explained the BYU-developed method, saying it turns some of the last two decades of public health upside down.

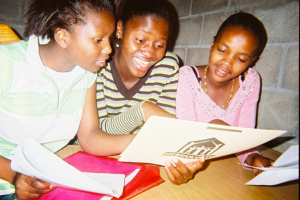

Typically, Westerners used to go into another country planning to implement a program developed by educated, Caucasian Westerners. The BYU team instead collaborated with local authorities and villagers. They invited natives to become co-researchers in hygiene promotion by recruiting individuals, mostly women, to train and learn from.

“We gained tremendous insight from the women who worked with us,” he said. “These women … thirst for knowledge and education, they want to be good moms, and they realize the importance of education.”

The local women helped the BYU team to understand and work within their cultural practices in the impoverished, rural areas outside of Cape Town.

“People would go to a witch doctor and say, ‘Gee, I have this problem with my lungs.’ … The witch doctor would likely sacrifice an animal and weave its hair into a necklace the person then wore,” Cole said. “We had to work our hygiene promotion program within the context of this culture, tradition, in some cases superstition … and respect those.”

A year later, the BYU team saw a dramatic decrease in disease and death.

A few years later the local women trained in healthcare and hygiene had not only become self-sufficient in their practices but had continued to teach other women and had even developed their own innovations, like making soap locally and cheaply.

“That’s a unique measure of success,” Cole said.

Though the study was conducted in South Africa, the same system would work throughout the continent, Cole said, and needs to be implemented to combat Ebola.

“We need more and more teams to go out into these rural areas throughout Africa and recruit individuals from these communities, educate them, train them in their culture and language … it just has to be relentless,” he said.

But while the fight against Ebola in Africa will continue for years, the U.S. remains virtually Ebola-free. Those in the US. might view the threat as distant because the reaction to disease here — culturally and medically — is so different, said Gaye Ray, a professor in the BYU nursing department.

“In the U.S., we are very well organized, and the hierarchy is very well established,” she said. “People are quick to disseminate … we are such an evidence-based system … we don’t react hysterically. … Even if some terrible, horrible disease (strikes) here, we would be able to rapidly deploy.”

Yet the U.S. can’t afford to let Ebola spread unchecked.

“The scariest thing is that all these diseases are only about a plane ride away,” Ray said.

But the BYU nursing department does what it can to help.

“Professors here have been participating in national conference calls and contributing some of our thoughts,” Ray said.

BYU nursing professor Peggy Anderson shared another tool that could be impactful: social media and music. A rap by Dr. Ground Zero, known as the Ebola rap song, for example, explains how Ebola spreads and how to prevent it.

“I think this rap is going to be powerful because it gives correct, culturally appropriate information about … avoiding dead bodies and trusting healthcare workers,” Anderson said.

Trusting healthcare workers has been a problem over the past few months. Cole explained how natives in West Africa sometimes see healthcare workers with suspicion because though they bring those with symptoms to a healthcare facility, the ill often don’t return.

“In many cases those individuals (healthcare workers) took were infected with Ebola and they were treated, but they died. So members of the communities saw — there are a group of health professional who … took away those people who are sick and never brought them back.”

However, despite the monumental challenges in overcoming Ebola, Cole said he is hopeful about eradicating Ebola in Africa.

“It’s a daunting task, but I’m optimistic we can do it. It’s just going to take a number of years,” he said.

Also read: Utah on guard for Ebola