As the war in Ukraine approaches two years and the Israel-Hamas war continues to receive international attention, the term genocide has reached millions of people on Instagram alone.

Notably, as of Dec. 12, 2023, #genocide had approximately 936,000 Instagram posts, while 346,000 posts linked to #gazagenocide and 13,100 posts read #genocideofukrainians.

The history of the term genocide dates back to the end of World War II.

In 1946, the United Nation’s General Assembly defined genocide in “The Genocide Convention.” Article II of the convention lists specific conditions which, when met, constitute a genocide.

“In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group,” Article II said.

Actions such as killing members of a group, causing serious bodily or mental harm, inflicting destructive conditions of life, preventing births, and forcibly transferring children all constitute the crime of genocide.

Since its inception, genocide has been discussed in reference to conflicts in Myanmar and Rwanda.

In the last two years, organizations like the United Nations and the Helsinki Commission have turned the definition of genocide to two more conflicts: the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and the conflict in the Gaza Strip.

To allow BYU students to weigh in on their personal understanding of genocide, The Daily Universe conducted a four-question anonymous survey of 46 BYU students.

The Data

Of the 46 students interviewed, all 46 indicated “yes” when asked if the statement “I know what the term ‘genocide’ means” applied to them.

Of those interviewed, 96% of the participants indicated they could identify a historical event where genocide was committed, while the remaining 4% indicated they probably could identify historical genocide. No students indicated they could not identify a historical genocide.

The final two statements asked students to apply their understanding of genocide to the two conflicts identified by Instagram hashtags #genocide: Israel-Hamas and Ukraine.

When asked to give their opinion on the statement: “I consider what is currently happening in Ukraine a genocide,” students gave a variety of responses.

Two students answered “yes” (4%), while 10 answered “I need to get more information – leaning yes” (22%), 14 answered “I need to get more information – leaning no” (30%) and 20 students (43%) answered “no.”

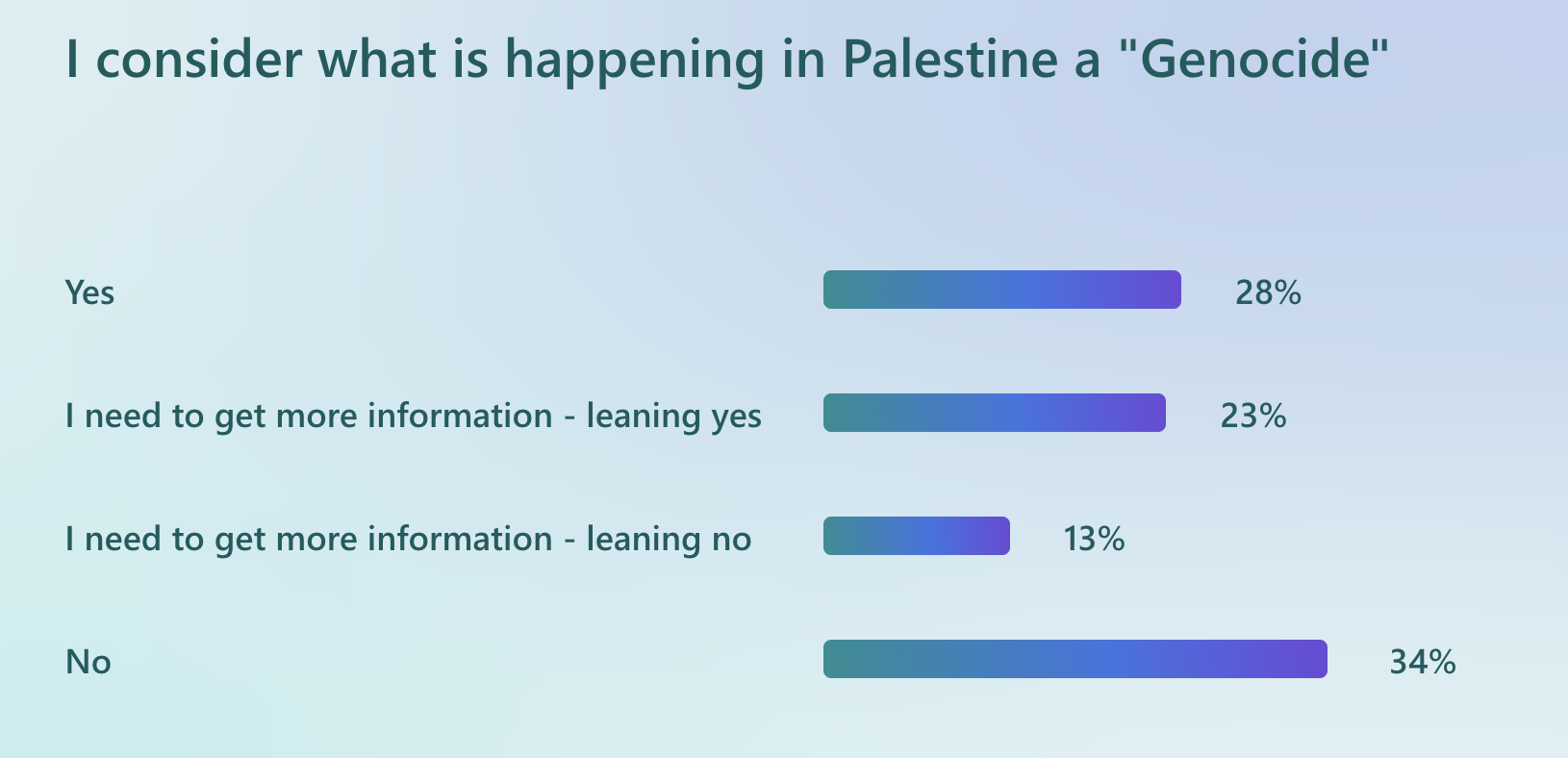

The statement about Israel-Hamas had even more variation in student responses.

13 students answered yes (28%), while 11 answered “I need to get more information – leaning yes” (24%), 6 answered “I need to get more information – leaning no” (13%) and 16 students (35%) answered no.

BYU students and staff read the results

Although the majority of students indicating they could identify genocide seemingly contradicts the variety of opinions about the events in the Gaza Strip and Ukraine, Eric Jensen, professor and global programs faculty director at the J. Reuben Clark Law School, explained there is a reason for this inconsistency. He indicated that much of the confusion in applying genocide to certain conflicts comes from intent.

“(The intent aspect of it is) that when you kill a whole bunch of people, you have to be killing them for the purpose of wiping them out,” Jensen said. “You might be killing a whole bunch of people just because you want to get everybody out of that piece of land. That’s not genocide.”

But intent is difficult to confirm, according to Jensen, as it is often implied.

“Intent in domestic criminal law is almost always inferred because it’s very seldom someone will say ‘Ha! I’m going to go do this crime,’” Jensen said.

Tom Krumholz, manufacturing engineering major, said in his opinion, there is another explanation for the confusion: there are two working definitions of genocide. One is popularized and discussed on social media and the other is reserved for academia.

“I think that the popular online definition is different from the political science definition,” Krumholz said. “The online term is used in a much more emotionally charged way with less parameters while the political science term is more defined and less commonly used.”

Interdisciplinary major Emma Soper said she has noticed an increase in discussion of genocide on social media.

“I have seen a lot of posts on TikTok and a few from people I follow on Instagram,” Soper said.

Sawyer Strikland, an undeclared major, said he feels the online sphere often adjusts the definition of terms as they become part of public conversation.

“In more recent days, I believe people online take certain terms or phrases and appropriate them for their cause or their own personal argument without knowing fully what the term means or being very selective in its application,” Strickland said.

Carley Parrish, a political science major, said that although the media might be adjusting the definition of genocide, the United Nations needs to revisit their definition as well.

“I believe that the international community should be trying to prevent genocide from the beginning rather than intervening when all the (definition) boxes are checked,” Parrish said. “While the media may use it too lightly, I do believe the (United Nations) definition needs to be altered.”

The discourse continues

Tony Brown, German and Russian professor, suggested the increase in the discussion around genocide could be a means to revitalize the discussion of conflicts in Russia and Israel.

“There is real concern in Europe and amongst many of our folks in Congress, that public support is waning,” Brown said. “This is speculation, but perhaps one explanation, as you say, for the uptick in accusations of genocide has something to do with trying to, as it were, sort of reinvigorate the public discourse around this subject and show, ‘look, this isn’t something we can turn a blind eye to.’”

As discussion continues to increase, Brown explained it is difficult for the international community to label a conflict as genocide.

“And that’s the hardest part,” Brown said. “I mean, you can show that all these terrible things are happening, but until you can link it to a certain discourse it’s hard to be able to make a case for genocide.”

Recently, the United States charged several Russian citizens with war crimes while the United Nations recently had a vote for an immediate humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza.