U.S. congressmen introduced expansions to the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act in May 2023 as advocates point to the lingering effects of atomic testing in Nevada.

While the amendments may be new, nuclear problems for residents began in 1945 with the first nuclear test in Trinity, New Mexico as depicted in the new Christopher Nolan film, “Oppenheimer.” Unfortunately for residents nearby, testing continued.

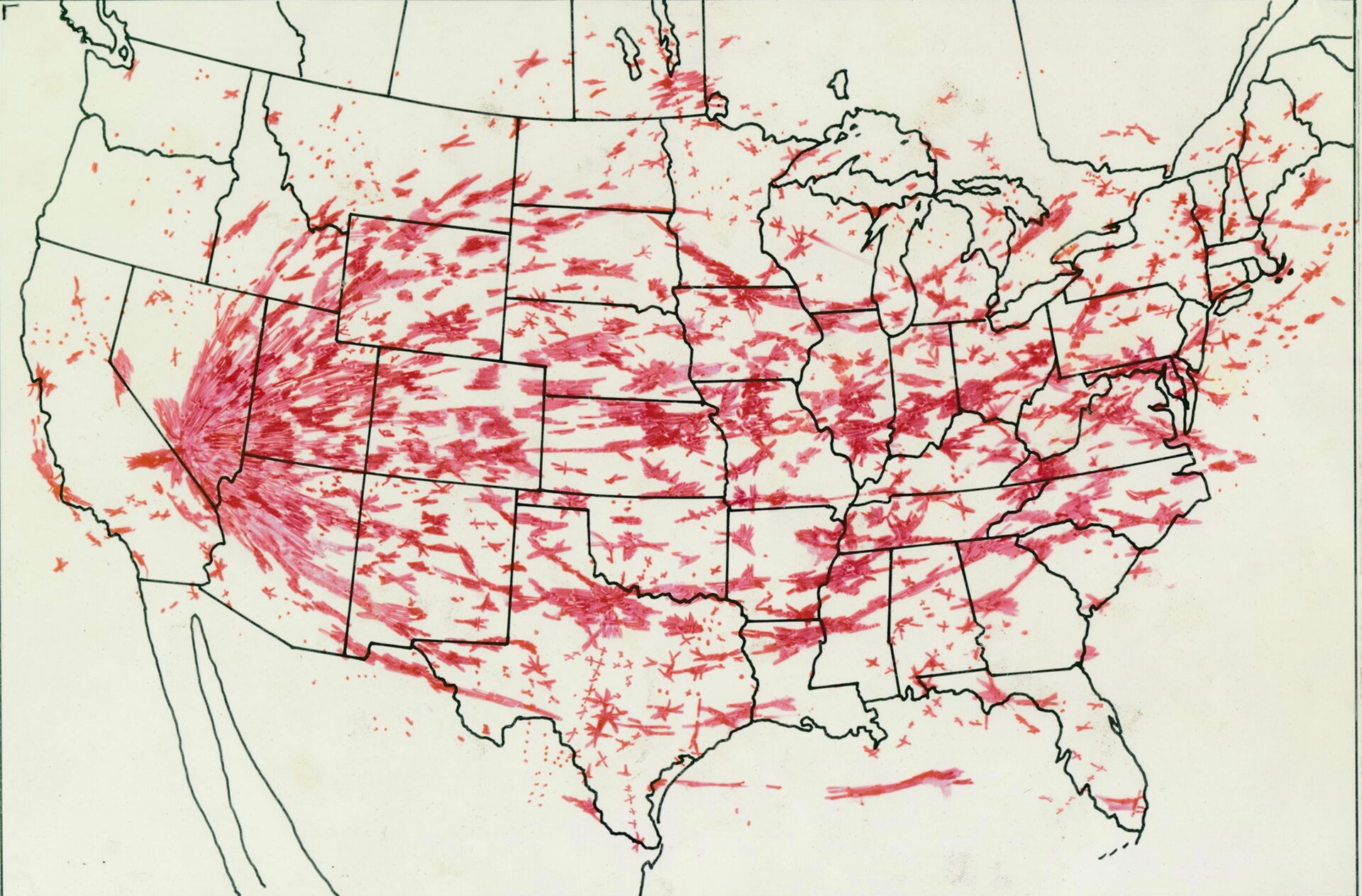

At the height of the Cold War and beginning in 1951, the U.S. tested hundreds of nuclear devices at a site in southern Nevada. These tests continued for decades and spread cancerous nuclear fallout across the U.S., especially affecting those directly downwind of the blasts in southern Utah and Nevada, and spreading beyond to areas like Salt Lake City, according to Mary Dickson, a downwinder and RECA advocate.

“If you thought that one bomb was horrifying to watch, keep in mind that in the U.S., on our own soil in Nevada, we detonated 928 nuclear bombs.”

Mary Dickson, downwinder and RECA advocate

The proposed amendments to RECA would expand compensation for cancers caused by the testing to several new states including Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, parts of Nevada and Utah and the territory of Guam.

Last year, when RECA was slated to expire, Congress voted to extend the program for two years. Advocacy groups, such as the Healthy Environment Alliance of Utah, are enthusiastic about the opportunity to amend RECA to benefit those who continue to be affected by the fallout.

Carmen Valdez, a Policy Associate at HEAL, explained the current shortcomings of RECA, including the geographic compensation line drawn across Utah.

“So if you live just one county up from that designated line here in Utah, but you were still in the fallout because fallout doesn’t stop at drawn lines on a map, you are not eligible for compensation,” Valdez said.

Specific dates set by the initial law also hinder some from receiving RECA benefits. Lance Benchley of the National Cancer Benefits Center shared a story of a family that moved to a county covered by RECA and failed to receive adequate compensation after the death of the father.

“They won’t pay on it because he wasn’t there for the entire month of July. I’ve had people who were born on July 2, and it says you had to have been out of your mother’s womb prior to July 1,” Benchley said.

Many residents of the states subjected to downwind fallout still suffer from the effects of the testing, according to Dickson. She was born in 1955 and started fighting thyroid cancer in her 20s. She stabilized after numerous surgeries.

Dickson saw the consequences of radioactive fallout starting when she was at home in Salt Lake City during the testing.

“I counted 54 people in a five block area who got tumors, cancer, autoimmune disorders. I mean, there was an eight-year-old friend of mine who died of a brain tumor. Four weeks later her brother died of testicular cancer,” Dickson said.

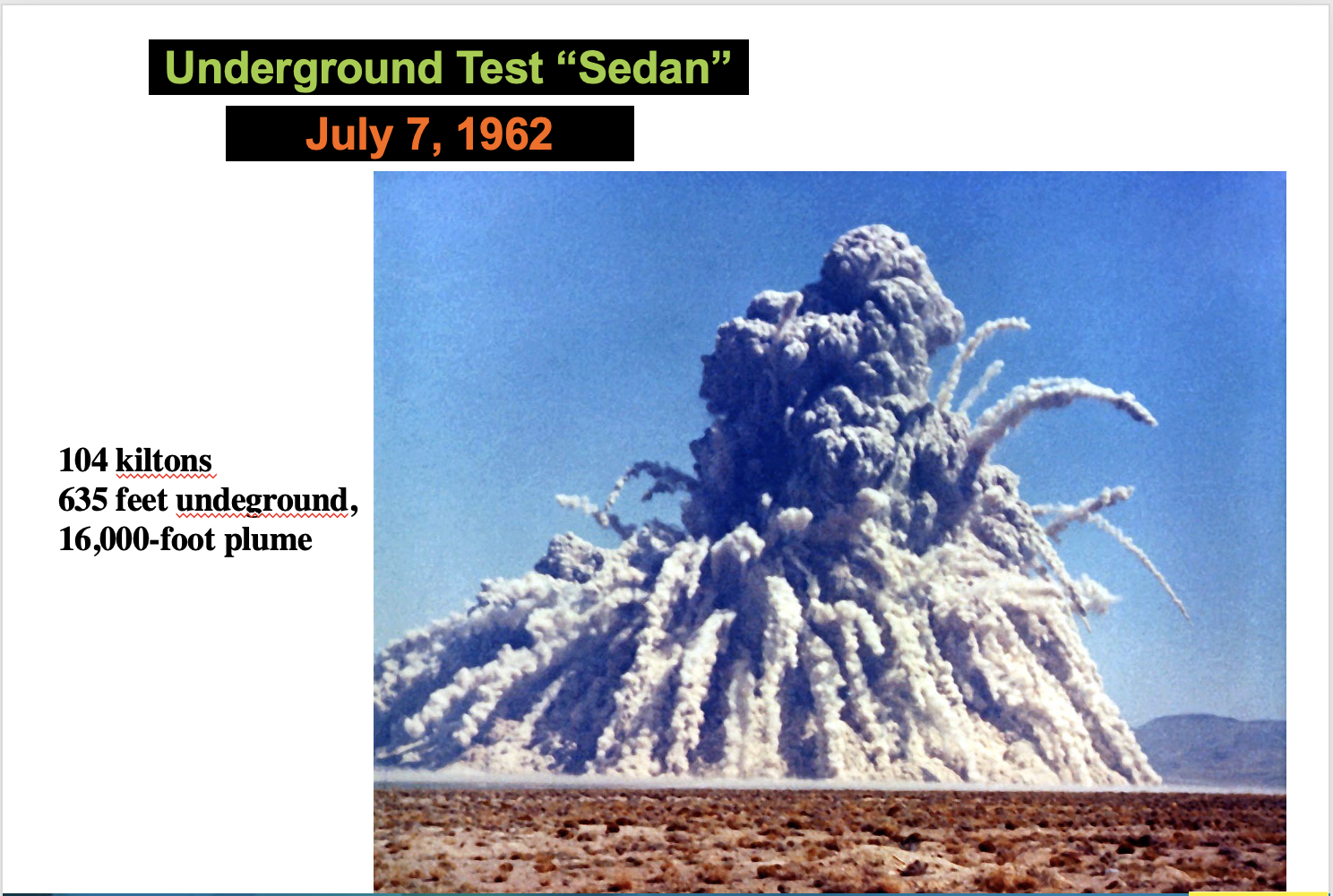

The above-ground testing of nuclear devices on the Nevada proving ground ended in 1962, according to Dickson, but the underground tests continued until 1992.

Underground tests also exposed residents to fallout, and Dickson personally saw the results in her life. She continues to observe the hardship caused by the testing.

“My sister died of an autoimmune disorder. A younger sister is currently battling stomach cancer. I’ve lost countless friends, neighbors and relatives over the years. Everyone I worked with on this issue so closely with for so long, they have all died,” Dickson said.

Generational problems among the descendants of downwinders are also prevalent in the states proposed for RECA coverage. According to some studies, female reproductive organs are especially susceptible to radioactive toxins.

“We’re seeing children of those exposed getting sick. Future generations are still being affected. So it’s not over,” Dickson said.

Nuclear byproducts such as plutonium-239 remain in the environment and can still pose some risk to residents. Radioactive isotopes like plutonium can linger in the soil for 24,000 years, or, as Valdez said, “a really, really, really, really long time.”

Although, the Environmental Protection Agency reports that many of the most harmful elements, strontium and cesium, broke down 30-40 years after the testing.

Valdez also explained the plight of some residents in southeastern Utah who can still be exposed to large doses of radiation through abandoned uranium mines. Some legislators are also drumming up support for further mining in the area.

“Unfortunately, a lot of the processes of processing uranium still allow for radioactive exposures and cause illnesses and sicknesses,” Valdez said.

According to Valdez, the current iteration of RECA would not cover or compensate exposed miners for their work.

Advocates like Valdez and Dickson continue to fight for more compensation from RECA and protection from future nuclear tests and industries.

“Radiation exposure like this can’t be solved in one bill,” Valdez said.

For the general public, Dickson lauded the release of the new Christopher Nolan film “Oppenheimer” as an excellent commentary on the nuclear issues.

“If you thought that one bomb was horrifying to watch, keep in mind that in the U.S., on our own soil in Nevada, we detonated 928 nuclear bombs. 928. All far more powerful than the one that Oppenheimer helped create. All more powerful than those that we actually dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” Dickson said.

Advocates like Dickson, Valdez and Benchley all encourage the public to educate themselves on nuclear issues and contact their local congressmen to help prevent future testing and expand RECA compensations.