Editor’s note: This story appeared in the January 2022 edition of The Daily Universe Magazine.

Patrick Alverson has been sober for about six years. When the COVID-19 pandemic first started and in-person meetings were cancelled, a friend of his started a daily Zoom meeting for people in recovery from addiction.

“Without that support group during the pandemic, I wouldn’t say I would be in a horrible place, it just would suck even more,” he said.

But Alverson also knows people who relapsed or struggled with substance addiction during the pandemic. He thinks it is because of how isolated people were.

“One of the things I hear in recovery is like, the opposite of addiction is connection,” he said.

There was a 29.4% increase in the number of drug overdose deaths nationwide between 2019 and 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In Utah, overdose fatalities increased by about 7% between 2019 and 2020, according to preliminary data from a Utah Drug Monitoring Initiative report released in October 2021. However, an earlier report from the Utah Department of Health, released in January of 2021, said there was not an increase in drug overdoses during the pandemic.

Opioid misuse in Utah County

Gabriela Murza leads Utah State University Extension’s HEART Initiative in Utah County. The HEART Initiative partners locally and nationally to address the opioid epidemic and other public health issues, according to Utah State’s Extension HEART website.

Murza said it’s hard to fully understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected drug-related fatalities in Utah because the most recent data is usually a year or two behind.

“2020 data for the state has been coming out recently. And just in general, Utah County is kind of following a similar trend to the state of Utah, and also to the United States,” she said.

Murza gave a presentation to the Utah County Commission in June about the opioid epidemic in Utah and the HEART Initiative. Murza told the commission the rate of opioid use disorder in Utah had been decreasing.

“Then 2020 hit and everywhere the numbers went up; they did increase as far as deaths due to opioids,” she told the commission.

The HEART Initiative operates in nine Utah counties, including Utah County, that have higher rates of opioid abuse and deaths related to opioid use. Carbon and Emery Counties have the highest rates of opioid overdose deaths in the state, according to the Utah Department of Health.

Changes in Opioid Prescriptions

Alverson lives in Orem and was first prescribed an opioid after an emergency gallbladder surgery at the age of 16. He had previously used other substances, like alcohol and marijuana.

“They (opioids) did nothing for me at the time,” he said. “My first opioid addiction came in when I was 21, when I hurt my back.”

Alverson said he was prescribed 30 milligrams of oxycodone when he was 16 and was prescribed 80 milligrams of oxycontin when he was 21. After his back surgery, he started getting prescriptions from multiple doctors.

“I was able to ‘doctor shop,’ so I can go to one doctor to get a prescription and go to another doctor and get another prescription,” he said. “One prescription will be paid by insurance, and the other prescription you gotta pay in cash.”

Around 2013, some of Alverson’s friends told him “doctor shopping” was becoming riskier and Alverson said his insurance stopped covering his opioid prescription, so it was too expensive.

Over the last decade, several laws in Utah have been passed to combat the opioid epidemic. For example, HB 175 “Opioid Abuse Prevention and Treatment,” passed in 2017, requires “substance prescribers to receive training in a nationally recognized opioid abuse screening method.” HB 50 “Opioid Prescribing Regulations,” also passed in 2017, limited the number of days an opioid can be prescribed for a patient.

But after Alverson couldn’t get prescription opioids, he started using heroin.

“I had never done heroin until 2014,” he said. “Besides, heroin is so much cheaper and a lot more potent than synthetics.”

About 80% of people who have used heroin first misused prescription opioids, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Alverson said he suspects more people turned to illicit drugs, like heroin, during the pandemic since many medical offices were closed or seeing fewer patients.

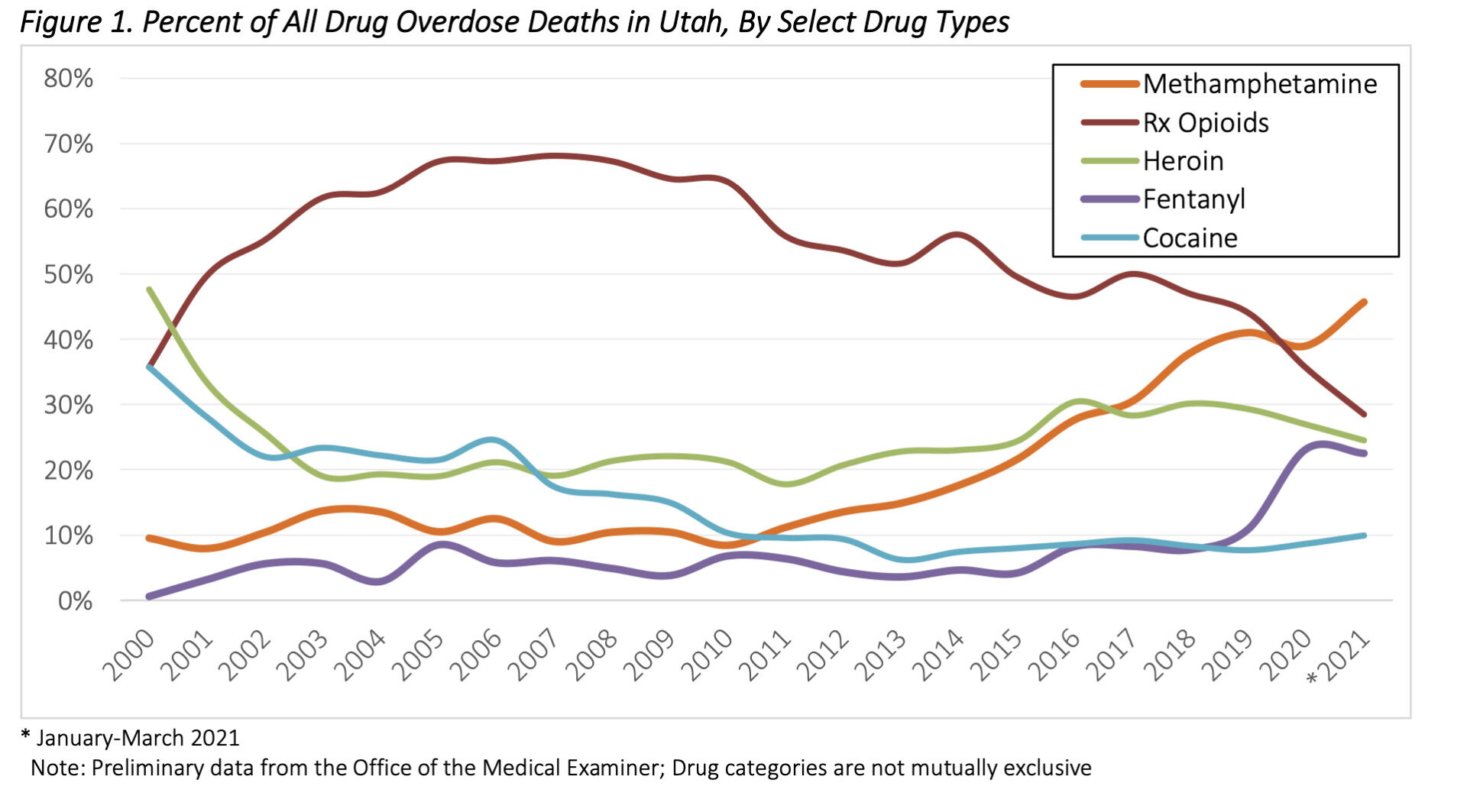

The annual Drug Monitoring Initiative report for 2020 includes preliminary data from the Utah Office of the Medical Examiner on drug-related fatalities. The report shows that for the first time in 20 years, prescription opioids were not the most common drugs involved in overdose deaths.

Methamphetamine was the most common drug involved in fatal overdoses in 2020 and fatal fentanyl overdoses increased by 125% from 2019 to 2020 according to the Utah Drug Monitoring Initiative Report. Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid but is several times more powerful than other opioids, according to the CDC. Non-prescription drugs can be laced with fentanyl. Murza said the increase of opioids laced with fentanyl has played a big role in the rise of opioid-related deaths.

“People just don’t know what they’re buying. They don’t know if it has fentanyl in it,” Murza said. “Fentanyl by itself is pretty potent, so to mix it with something else that’s potent as well, it’s not a good thing.”

Alverson said most of the people he knew who used opioids did not get them from a doctor’s office.

“You can buy more drugs on the street than you can in a doctor’s office,” he said.

Stigma

Murza said that while there have been legislative changes, there is still a lot of stigma surrounding opioid addiction. She said from talking with people in Utah, the biggest misconception she’s seen is the idea that if a person has opioid use disorder, they are to blame for their addiction. Murza also said she prefers the term “opioid use disorder” as opposed to “opioid addiction.”

“A person is not their addiction, a person is not the challenge that they’re facing,” she said. “The biggest thing is helping people understand that there are humans behind any challenge, anything that somebody is experiencing.”

To help humanize the issue, the HEART Initiative created a digital library collection that features stories from Utahns affected by the opioid crisis.

Nathan Ivie, a former Utah County Commissioner, told The Daily Universe that another misconception in Utah County is that only certain types of people have opioid addictions.

“It’s non-discriminatory, it affects a lot of people,” he said.

Ivie’s mother had a knee replacement and was prescribed a heavy narcotic. He said she had struggled with depression before the surgery and narcotics not only took away the physical pain, but also helped with the emotional pain.

“That led to an addiction. We found out about it when she came off of it, she went through withdrawals,” he said.

She had her other knee replaced a couple of years later and had a similar problem. Except this time, Ivie and some of his family members told her doctor about his mother’s experience during her last surgery.

“What happened that second time, it was kind of a similar thing, we had to take them away,” he said. “We had to highly regulate her medication intake, she went through withdrawals again.”

But Ivie said he doesn’t think his mother would’ve considered herself addicted to the medication because she was just taking what was prescribed to her.

“Utahns, particularly members of the LDS faith, are taught to trust authority figures, right,” he said. “And so if the doctor is saying to do this, it’s inherently okay.”

Alverson had another back surgery in 2017, while he was in recovery, and he said that was the first time he had a prescribing doctor talk with him about how opioids can be addicting. The doctor also talked with him about his recovery, what medication might be right and the dose.

“They only gave out a week’s worth of medication and not the whole month,” he said. “If my previous doctors had done what this doctor did while I was in recovery, it would’ve been a tremendous help.”

Alverson wishes more people knew about and had access to Naloxone or Narcan, medications that can reverse an opioid overdose and said there are a lot of unnecessary deaths because of overdose.