Brad Martin and the high cost of opioid addiction

Story by Addysen Kerr. Cover art by Emme Franks.

This story is part of the November 2021 issue of the Daily Universe Magazine and Universe Live Magazine Show.

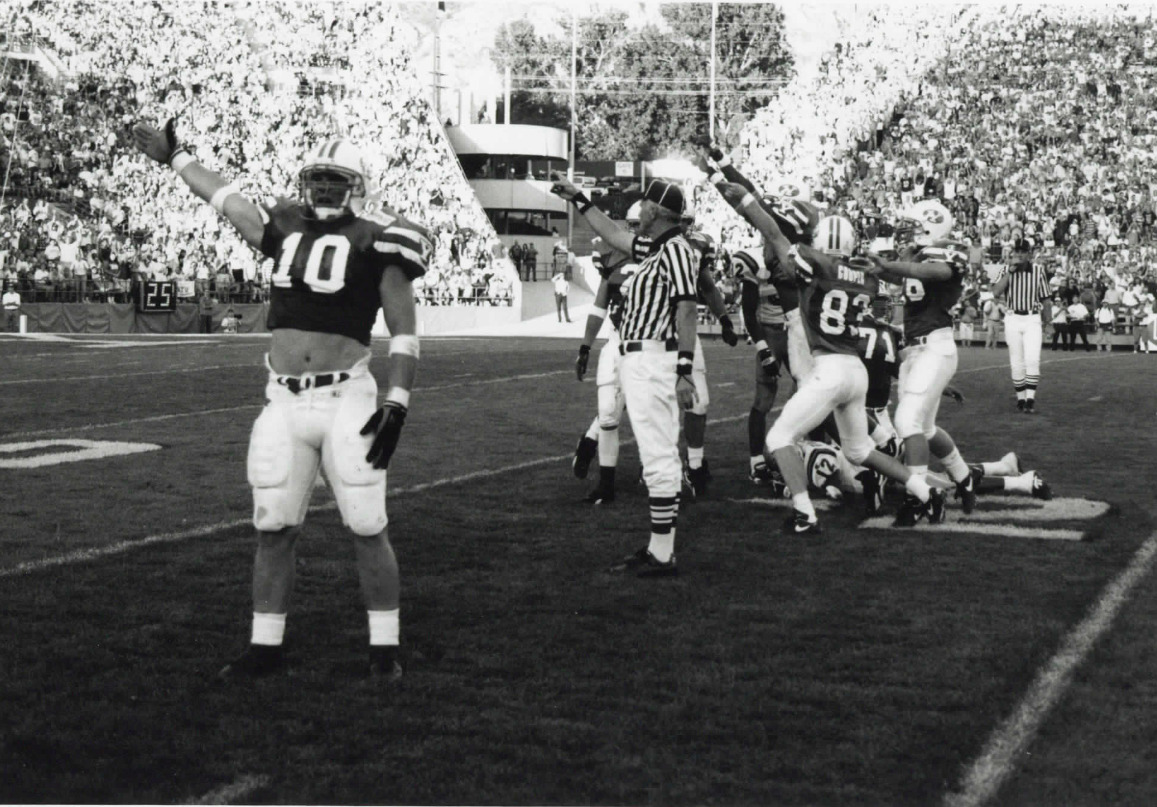

The BYU Cougars and Arizona State Sun Devils had just retreated to the locker rooms for halftime amid deafening cheers. BYU was leading 21-7.

Out walked 40 men onto the field. Each dressed in white Nike BYU polos to match the 60,000+ fans in the stadium watching them.

Some of the men waved, some smiled, some pulled their phones out to record the celebration. Each one was a member of the 1996 BYU football team, the first team to win 14 games in a college season. They are considered by many to be the best team in BYU history.

On Sept. 28, 2021, these teammates were honored for the legacy they left at BYU 25 years ago.

“It was a great event and it was a great experience that the school put on for our team,” said Derik Stevenson, a former BYU linebacker.

But Stevenson couldn’t help but feel that someone was missing.

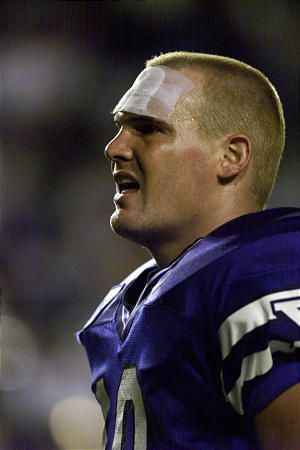

Senior co-captain of the football team (a sophomore during the legendary ‘96 team), Brad Martin, was involved in a car accident that knocked him unconscious, causing severe whiplash, and cutting his forehead, requiring 7 stitches right before the BYU v. Arizona State game in September of 1998. Against his parents’ wishes, he refused to miss the game.

During the game, the car accident was all but forgotten. The 6-foot-1-inch, 240-pound linebacker made six tackles, and BYU beat Arizona State, 26-6.

But the consequences for that decision came after and haunted Martin for the rest of his life.

Team doctors prescribed Martin opioids in the hopes that it would be enough to get him through the resulting pain from his car accident. They didn’t fix his pain, but they did dull it.

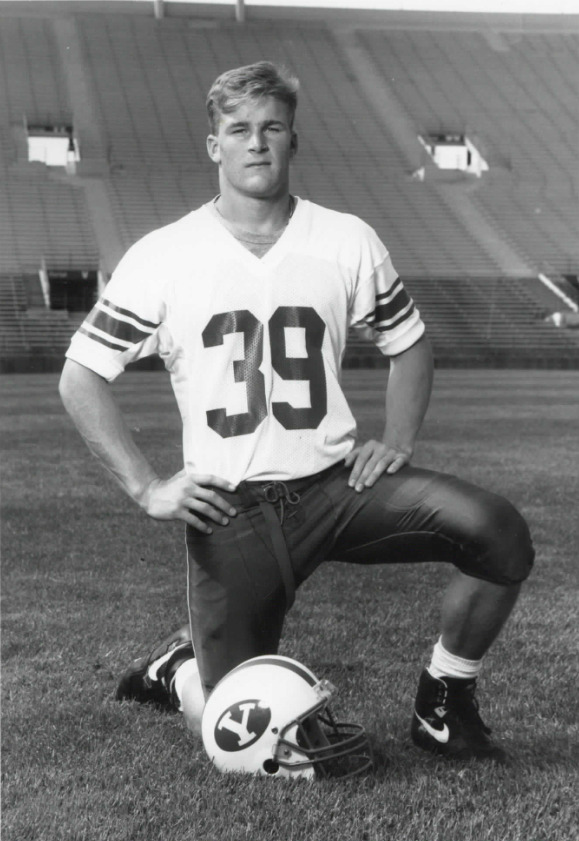

“He was a tough kid, real tough kid, pretty no-nonsense, you know?” said Shane Magalei, former defensive lineman, and one of Martin’s teammates.

Teammates say Martin was one of the happiest, most positive guys they’d ever played with; one of their all-time favorites. He never wanted to let anyone down.

“You saw how hard he worked and everything that he went through. He hated not being able to be on the field with his teammates and his brothers. His personality and his commitment to the team, and his commitment to try and never miss a practice or never miss a game so he could be alongside his brothers. That was what impressed all of us the most about Brad,” said Stevenson.

Stevenson thinks Martin’s commitment to the team and to playing is one of the things that eventually led to his addiction to painkillers. Once he was done with football, the pain didn’t just magically disappear.

It was still there.

Harland Ah You, another defensive lineman, works in addiction recovery. “(Martin) was always a team guy first. I saw his struggles physically, but I didn’t know what they were. But I know what the struggle is after you’re done when you’re in pain and you can’t live a healthy life, the struggles that come from not understanding all the stuff you turn to to help you stop.”

At the end of the season, doctors discovered Martin had three herniated discs in his back, most likely stemming from untreated injuries caused by his accident four months prior, and constantly getting hit on the football field.

He continued taking opioids long after he left BYU.

Eventually, his addiction led to an arrest, and a divorce.

Why didn’t Martin try to get help?

The shame and guilt that came along with addiction were heavy. Athletes were afraid they’d be kicked out of school for breaking the Honor Code. And there weren’t enough resources for them once they left the university.

“There’s a pride factor that comes into it too. Brad was really proud, which was a good thing in a lot of ways, but also, former teammates don’t like to reach out to the other guys even if they’re really close to them, and really admit that you have problems, or challenges, or shortcomings, or issues with things like that … Because you don’t like those guys to see that maybe you are weak in some way and need help,” said Stevenson.

When you’re praised for being one of the toughest guys around, it can be devastating to shatter that image.

“That’s the one thing that Brad never did. He just suffered in silence for a long, long time. He tried to put on a good face … they never have enough humility to, to reach out and just say, guys, I’m broken. I need help,” said Stevenson.

The Martins sued BYU in 2004. According to an article in the Deseret News, “In the court documents, Brad Martin contended that BYU ‘continually allowed me to play football despite my injuries’ and ‘provided me with an abundance of painkillers … to allow me to play through the pain in my last football season.’”

Without health insurance, Martin’s parents couldn’t afford to pay for his rehab. They just needed a little help. The lawsuit was settled outside of court, and BYU ended up paying for two different rehabs. One was 30 days in southern Utah, and the other was 90 days in northern Utah.

“It didn’t matter if it was a film session or it’s time to be quiet, Brad’s loud. Or trying to go to sleep, it’s after curfew, Brad’s loud. I mean, he just had that where he was like lightning all the time …” said Isaiah Magalei, a former defensive linebacker.

“Whether the coaches were (upset) or you’re going to have to run because of it, he just laughed, because that was him, and it was contagious. He definitely had that personality where you wanted to be a part of it.”

He remarried after rehab and moved to Salt Lake City. The marriage was very brief.

Martin died alone in May 2006. His landlord found him on the hallway floor in the home he was renting in Sugar House, almost six days after he had passed. He was 30 years old.

Athletics and the opioid epidemic

As with most things, opioids were developed with the best of intentions. Their purpose was to relieve people of their pain, or, at the very least, allow them the ability to manage it better.

Early research on opioids showed they were only addictive if they were used recreationally — not if they were used to treat pain.

The article, “Tracing the US opioid crisis to its roots” states, “in the United States, the idea that opioids might be safer and less addictive than was previously thought began to take root. A letter to the editor in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1980 reported that of 11,882 hospitalized people who were prescribed opioids, only four became addicted, but the short letter provided no evidence to back up these claims. A widely cited 1986 study, involving only 38 people, advocated using opioids to treat chronic pain unrelated to cancer. The prevailing view is that these studies were over-interpreted.”

Big pharmaceutical companies advocated for their usage, claiming they weren’t addictive, when in reality, there was no proof of this; companies knew all along that they could cause very extreme addictions. However, doctors and patients weren’t aware of this at the time.

Opioids were cheap to produce and cheap to purchase, ultimately putting more and more money in big pharma’s pocket. Doctors didn’t get very much training on pain management, so they thought they were being compassionate when they prescribed a patient opioids — to help with the pain.

There were three phases of the opioid epidemic.

First came prescription opioids. A patient needed a doctor to prescribe them in order to obtain them.

Second, heroin. Once doctors realized the addictive nature of opioids, they changed the regulations, making them much harder to obtain. Users then switched to heroin because it was easier to get.

And finally, synthetic opioids that were even cheaper, and more potent, than heroin. Users that still had opioid prescriptions could now sell their leftover pills at an increased price, which only accelerated the epidemic. More options to use equals more users.

While the epidemic had its start in the ’80s and ’90s, the crisis got worse around 2017. According to Nature.com, “The death rate from drug overdoses more than tripled between 1999 and 2017, and that from opioid overdoses increased almost sixfold during the same period.”

“It wasn’t an issue back then, the opioid issue. It was a pretty commonplace thing for people to get some prescriptions,” Ah You said. “As an athlete, things were readily available because you were in pain.”

“I think at the time, the doctors, I don’t blame the team doctors or the team because they were all kind of learning at the same time as us players were learning about some of the issues that could really happen when you do take a lot of pills,” Stevenson said.

So what can be done when it comes to college athletes and opioids?

“I believe if you give a guy a prescription, they shouldn’t be attached to a concept. If you’re going to prescribe an individual pain medication for an injury, along with that pain medication you have support around that,” Ah You said. “And there’s no way you can get more or they can talk about more until they’ve had a chance to visit about what it can do to you and how it can affect you in the future. I think that would be a super solution for a very, very difficult addiction.”

“It’s hard to balance a culture where you’re trying to make kids warriors and make them strong,” Shane said. “But at the same time, you’re trying to teach them the difference between being hurt and being injured, right? Because being hurt, you just gotta tough it up and suck it up. But if you’re injured, you can make things worse.”

Shane says football needs to find a way to balance the culture — are you hurt, or are you injured? Are you just trying to get out of running, or are you covering up your pain so you can play in the next game?

Coaches need to be accessible to and vulnerable with their players, and help them realize that although playing is important, and their team is important, their overall health needs to come first.

Stevenson says that programs and universities, and the NCAA, need to recognize the toll, mentally, physically, and emotionally, being a student-athlete can take on a person. They need to be understanding. Student-athletes make money for them and they need resources to help them, not only while they’re in school, but also when they come out of it.

“I think something that would have been helpful for Brad, for me and lots of others would be what Kalani does with the guys now. He really prepares them to deal with issues like that,” Stevenson said. “I had no idea at 24 and I don’t think Brad did. You know, at 21, I don’t think we were prepared or educated.”

BYU football and overcoming addiction

Martin isn’t the only one whose addiction started during his time playing football for BYU.

On Sept. 5, 1998, just a week before Martin’s car accident, the team hopped on a plane to return to Provo after their 38-31 loss to Alabama Crimson Tide. Stevenson, the 24-year-old linebacker, boarded the plane in more pain than he’d ever experienced.

Both of his shoulders had been separated.

Team doctors gave him a small manila envelope, pills inside, to take as directed until he could get a doctor’s appointment the next day. Instead of taking the pills as instructed, he swallowed a few and sprawled out at the back of the plane to sleep for the long return flight home.

“I just wasn’t really prepared to deal with, you know, how the drugs were going to make me feel, how much I would learn to like them throughout the course of the entire season,” he said.

There is a lot of shame and guilt that comes along with addiction, says Stevenson, especially while attending BYU.

Players that struggled with addiction were afraid to ask for help, not only because they didn’t want to be seen as weak, but because they were worried they’d get kicked out of school or lose their scholarships.

“I think now the BYU Honor Code is a lot more willing to give somebody amnesty if they come to them and they say, ‘hey, I’ve got a problem.’ For a long time it was like, well, you have a problem, you’re no longer a good representative of BYU football,” said Stevenson.

Stevenson kept his addiction a secret for fear of getting kicked out of school. There was a stigma attached, not only to addiction, but especially to those that struggled with addiction that were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, while playing at BYU.

Though Stevenson only took opioids his senior season of football while others took them for all four years, it was more than enough to cause major problems in his life.

He, like Martin, went through a divorce not long after he left BYU. But unlike Martin, he has been clean for the last six years.

Stevenson now advocates for recovery and does his part speaking to current college athletes about his story and the reality of addiction.

“I just decided that I needed to start being more honest and vocal, and not be so ashamed.”

Max Hall is BYU’s winningest quarterback of all-time with a 32-7 record. He played at BYU from 2006-2009.

He went on to start for the Arizona Cardinals in 2010, but suffered a shoulder injury and multiple concussions within the first few games. He lied to team doctors about how severe his injuries were because he didn’t want to lose his starting position.

He was prescribed pain pills to allow him to be able to play. After three days, the bottle was empty. All he could think about was how he was going to get more.

Hall’s addiction to opioids continued for years. It all came to light when he was arrested at a Best Buy in 2014 with hundreds of dollars worth of stolen electronics in his backpack. At the time, he’d not only taken oxycontin, but also cocaine.

“One of the hardest things in my life was sitting in the back of the cop car, handcuffed, thinking, it’s over. I’m done. This is gonna get out. I’ve ruined everything. I’ve lost everything. I’ve lost my family, my credibility, my character, my reputation. I’m done,” Hall said in episode 262 “Life Lessons with Max Hall” of the Becoming Your Best podcast.

“I didn’t think I needed help. I thought eventually I could just get through this and I couldn’t have been more wrong.”

Hall told his wife and dad that he’d been arrested, fearing their reactions. He was terrified that his wife and children would leave him. Instead, his family stuck by him and supported him with the help he needed.

Not only was his family there for him, but former teammates and coaches reached out as well, voicing their encouragement in his recovery. Chad Lewis and Brandon Doman were two of the calls he received.

Hall was in rehab for three months. He realized that he had an addictive personality, and he was given tools and resources that changed his life.

“You’re gonna make mistakes. People make big mistakes, make small mistakes. My big mistake just happened to go public because I was a public figure and everybody knew what was going on with me. But what I came to find out is that doesn’t matter. What matters most is what you do next, what you do about it, and how you move on.”

Part of his rehabilitation journey included the knowledge that he couldn’t want to get better for anyone else; he had to want it for himself.

Not long after, Rich Edwards, head coach at American Leadership Academy in Arizona, decided Hall deserved a second chance; after deliberation with the board, Hall was offered the position as the offensive coordinator. The football program believed they could help him just as much as he could help them.

“I didn’t think anybody was going to give me the chance to do anything … it was life-changing for me.”

Despite his addiction, Hall has completely turned his life around. He now talks to athletes and youth groups about his story and the dangers of addiction and substance abuse.

“I can turn something positive out of something really negative that happened to me and almost ruined my life and use it to help others.”

On Sept. 28, 2021, the 1996 football team stood at the 50-yard line. While lights shone down and cameras zoomed in on them, someone from the crowd went from person to person, writing something on each teammate’s hand with a black Sharpie.

On everyone’s hand was the number 10, Brad Martin’s number.

“The whole team just talked about how we were being honored for having such a great team and such a great season in 1996, 25 years ago,” Stevenson said. “All of us knew something was missing, and we knew that it was that Brad wasn’t there.”