Dec. 16, 2017

Greg, 52, has spent the majority of his life in and out of homeless shelters due to his battle with addiction has been part of Utah’s homeless community for 17 years.

“I’m part of a community. We are the long-haired freaky people,” said Greg. “But look around, you see what they’re doing. All they’re missing is barbed wire.”

But the outlook for the homeless community in Utah is rapidly changing.

This year officials from all sides of state government came together in hopes of helping people like Greg by addressing the lawlessness surrounding Rio Grande.

However just twelve years ago homelessness experts applauded Utah for being the first state to implement “Housing First,” a program designed to focus on finding housing for the homeless before tackling other issues.

Timeline

The state’s efforts led Utah to hold the 14th lowest amount of all those experiencing homelessness on a given night in 2016. Compared to California, the state with the highest homeless population of 118,142 , Utah had just 2,807. However the numbers can be misleading since there’s no clear indication between a state’s overall population and its homeless population.

Utah saw how detrimental numbers can be in 2015 when Lloyd Pendleton, former director of Utah’s Homelessness Task Force, told The Daily Show that Utah saw a 72 percent decrease in their chronic homeless. The number officials gave media outlets even increased to 91 percent.

Reports on sites like NPR and the Washington Post quickly circulated that the state had ended chronic homelessness.

However soon after, the Huffington Post debunked the claims proving that the person-in-time count Pendleton and Utah’s Homelessness Task Force cited wasn’t a clear marker on assessing a state’s homeless population.

"Utah was a national joke." Hughes

“Utah was a national joke,” said Hughes. “It was silly to say we ended it.”

Recently Christina Davis at the Department of Workforce Services said that they try to focus on trends over multiple years to gain a clearer picture.

“That year was more of a fluke rather than on trend with previous and following years,” said Davis.

Hughes said, “It’s important we be careful when we look only at the numbers because it’s clear to anyone living in Salt Lake who looks out their window that homelessness hadn’t gone anywhere.”

Homelessness in Utah was in fact still happening and on one Salt Lake street, Rio Grande, it was running rampant.

“People were coming to me saying year after year it’s getting worse,” said Hughes. “And I thought well you don’t have to spend a dollar for it to be worse and we were spending tens of millions.”

Conversations like these and other national news spreading Utah’s urban chaos sent Hughes on a crusade to defeat Rio Grande.

Operation Rio Grande

Operation Rio Grande launched on August 14th of this year.

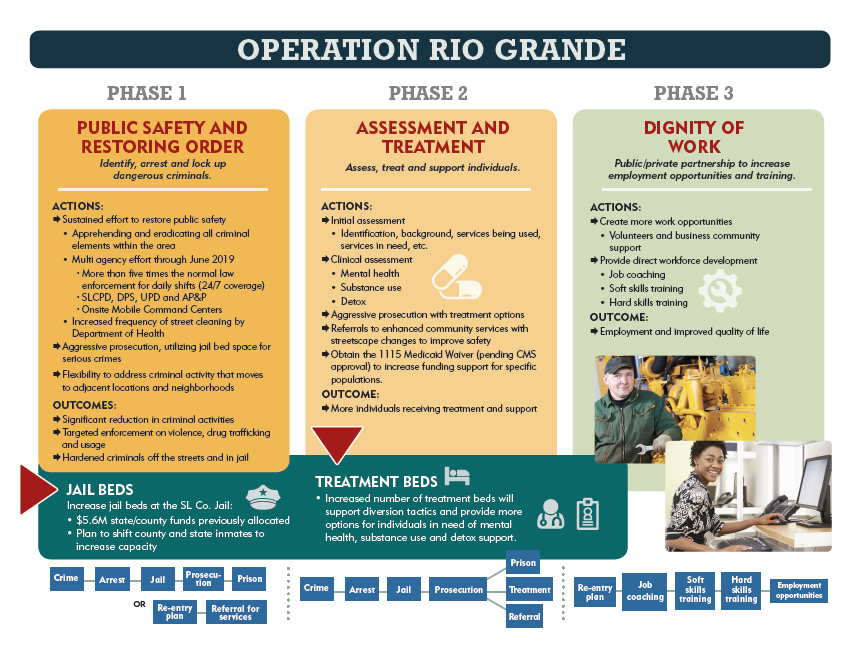

The state’s three-phase plan includes public safety and restoring order, assessment and treatment, and dignity of work.

Operation Rio Grande Three-Phase Plan Handout

Despite the Operation’s plan, much of the Operation has been overshadowed by the 2,000+ arrests since kickoff.

Some reports by the Desert News said that despite lawmakers claim to focus “the worst of the worst”- drug dealers, thieves, etc. many arrestees were low-level offenders.

Further investigation tells a different story.

Thinks to a criminal justice reform bill, Justice Reinvestment Initative (JRI), passed in 2015 state lawmakers decreased traditional drug felonies to misdemeanors.

According to a press release by the Utah Department of Corrections, “The intent [was] basically to continue holding offenders accountable and securing our communities — but in a way that takes into account individual risks and treatment needs.”

However, the bill’s unintended consequences included the rise in crime among the homeless.

When the Desert News reported that 759 arrests were made on alleged misdemeanor offenses compared to 221 felony offenses, it didn’t specify that misdemeanor offenses included drug crime.

Taking all this into consideration, the claim that Hughes’s wasn’t following his promise to focus arresting the “wolves” of society is untrue.

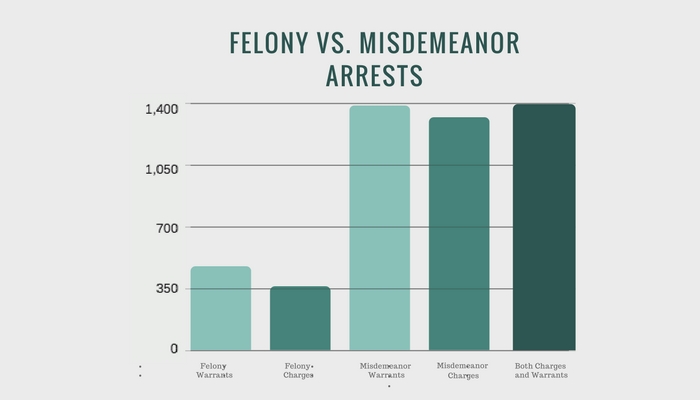

In updated statistics obtained by the Salt Lake County Jail as of November 16, 2017, of the 2,000+ arrests that had been made, 475 had felony warrants, 310 had felony charges.

1386 people had misdemeanor warrants and 1131 had misdemeanor charges.

796 people had both charges and warrants.

Understanding the changes made by lawmakers shows that the statistics don’t defiantly prove whether those arrested are the “wolves” or “sheep.”

Despite reporting, many experiencing homelessness disagree with lawmakers methods.

“Incarceration doesn’t do anything but make people angry,” said Greg. “You get to rest for a few days but what we need is help.”

Statewide Collaboration

When Hughes began his crusade, he decided to set up camp right across from the battleground in a storefront office at the Gateway Mall.

Speaker Hughes

“I wanted to see for myself what was going on,” said Hughes. “What I saw were people rolling spice joints. They were basically giving me the middle finger. They didn’t care.”

For weeks Hughes held various legislative meetings, even ones unrelated to homelessness, in the “war room” office in the hopes of showing others a change was needed.

With the help of Lt. Gov. Cox, Senate President Neidenhauser, Attorney General Sean Reyes, Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams, and Salt Lake City Mayor Jackie Biskupski, Hughes began a task force to change homelessness and restore social order.

Together they came up with Operation Rio Grande.

All their efforts led to the Utah Legislature passing two bills in August, funding the $67 million dollar price tagged Operation Rio Grande.

In a press conference, Hughes applauded the legislature for the “bipartisan support” on a “statewide issue.”

"Utah is very good at collaboration. For a very, very complex problem like homelessness it would be easy to be territorial on the state, city, county level." Davis

“Utah is very good at collaboration. For a very, very complex problem like homelessness it would be easy to be territorial on the state, city, county level,” said Davis. “So to be able to bring everyone involved to the table and work towards a common is an important part of our success in Utah.”

Despite collaboration and funding, Greg wondered where all that money was going.

“$67 million went somewhere. It didn’t go into redoing us. It went into the [police] harassing us,” said Greg.

History of Problems

The Rio Grande neighborhood is a centralized spot for all homeless service centers in Salt Lake City. However, a slew of problems turned the street into a lawless community.

“It was a good concept. The problems were that the scale overwhelmed the neighborhood and it was historically the place people went to find their vice,” said Salt Lake County Deputy Chief Josh Scharman. “We were fighting not only a current philosophy but a generational one.”

Not only did Rio Grande have a hard-to-break philosophy but it had a reputation across the state as well.

"Honestly, many Utahans think Rio Grande when they think of homelessness and nobody wants that in their neighborhood. I sure don't want it in mine." Walker

“Honestly, many Utahans think Rio Grande when they think of homelessness and nobody wants that in their neighborhood. I sure don’t want it in mine,” said Draper Mayor Troy Walker.

“We learned that a lot of people that need help with food or shelter were frightened to be in that area because they didn’t want to assaulted, have their things stolen, or potentially relapse into drug addiction,” said Hughes. “Those were the invisible barriers that were created in that area that people didn’t talk about.”

On top of a history of vice, an overwhelmed neighborhood, and a reputation, the introduction of JRI created a state of anarchy on Rio Grande.

“There wasn’t actually any treatment available [for JRI]. There was no financing, no funding, and no infrastructure in place. And the jail became so overcrowded that they turned down all misdemeanors,” said Scharman. “People knew that they could possess heroin and have zero consequences at all. Our population just exploded down there because it was a free drug-use zone.”

Scharman and Hughes both agreed that Rio Grande needed a change.

“We needed something of scale to happen. We needed something big,” said Scharman. “And that was Operation Rio.”

Results

Many of the advocates of the Operation believe it’s changed the neighborhood for the better.

“How can I sum up how things have changed? Immeasurable, massive, biggest turnaround I’ve seen in two decades of working down there,” said Scharman.

“If you were to go and walk around that area you’d see a marked improvement, even a lifting of spirits of people that are there. People are more conversant. People are making eye contact,” said Hughes. “You see a lot more people looking for help.”

But Operation Rio Grande isn’t without its criticism and it coms from both inside and outside the Operation.

Both Speaker Hughes and Scharman wish looking back that treatment beds had been available at the launch of the Operation.

“Any project of this scale it wouldn’t be responsible to look back and find opportunities to do better,” said Scharman. “There’s always ways you can improve.”

However outside of Utah, the criticism is deafening.

“If you were to go and walk around that area you’d see a marked improvement, even a lifting of spirits of people that are there." Hughes

Ben Cattell Noll, Technical Assistant Specialist at the National Alliance to End Homelessness said, “Homelessness is definitely a local need. Each community has different needs and solutions look different in each place. But when intervention is getting in the way and adding new barriers to people finding housing, that isn’t something we’d want to see. Jail is not a home and going to jail makes it more difficult to access a place in the future.”

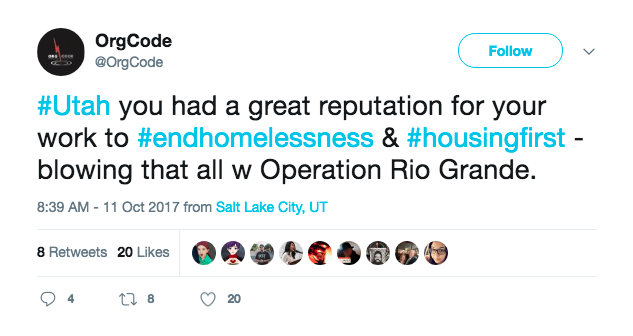

Noll isn’t the only one critical of Utah’s recent efforts. Homeless expert Iain de Jong made waves when he and Speaker Hughes got into an argument over Twitter after Jong tweeted:

Jong tweet via @OrgCode

Later that week Hughes told the Desert News he was “ready and willing” to debate Jong.

Choosing not to respond on Twitter, Jong, who is under contract with Utah to advise them on three new homeless resource centers, took to his blog to post his thoughts on Operation Rio Grande in full.

In the post Jong writes that the problems in Utah needed addressing but the approach was wrong. He applauded Hughes for doing his research but believes the criminalization of the homeless will only create more barriers for them.

"It is draconian. It is a huge, expensive step backwards for a community that used to give the rest of the nation so much hope." Jong

One of the major criticisms people have against Operation Rio Grande is the emphasis on treatment rather than housing.

“When we talk about homelessness we don’t have to be talking in the same breath about ending people’s mental illness, their drug or alcohol abuse, their poverty. Certainly all those things can be contributing factors to someone losing their housing but there not things that need to be solved before someone can get back into housing,” said Noll.

Greg, who is personally feeling the effects of Rio Grande isn’t it’s biggest advocate.

“They’ve made a corral and surrounded us with armed guards,” said Greg. “All [the Operation] is doing is scattering people across Salt Lake.”

Despite it’s criticisms, Operation Rio Grande presses on and is now in Phase 3 of operations.

Impact on Provo

Legislators on Capitol Hill frequently comment that Operation Rio Grande came from a statewide problem in Salt Lake, yet while officials center their attack on Rio Grande the effects are rippling throughout the state.

Locally, Provo continues its search for ways on dealing with transient camping and the effects of Rio Grande.

Earlier this year Saul Marqeuz, Daily Universe reporter, followed Sgt. Wayne Keith around Provo Canyon filming his experience. His video can be found below.

Marqeuz’s video illustrates why Keith and the Provo Police Department teamed with the Utah County Attorney’s Office in a proposal banning long-term transient camps in Provo Canyon and other local canyons.

The proposed ordinance would’ve made it easier for law enforcement to address the problem, as a current prohibition doesn’t exist in regard to long-term camps.

“Officers came to me looking for a solution to the homeless camps,” said Carl Hollen, Utah County Attorney’s Office. “And they said not only is it bigger every year but we started hearing rumblings in Salt Lake and as Salt Lake moves that problem out it’s going to move to Utah County. So we need to do something.”

The Provo City Council responded by passing an ordinance that banned camping on city property, including alleyways and parks.

In a panel discussion at the Women’s State Legislative Council of Utah County meeting last October Sargent Wayne Keith of the Utah County Sherriff’s Office said, “I see what’s happening out there. And this is the worst I’d ever seen,” said Keith. “We have a right to say enough is enough.”

Similar to other officials, Keith said that he attributes part of the problem JRI.

“Arrests went down and crime went way up,” said Keith. “What we need is more teeth to address the issue.”

However, the proposal Keith and Hollen hoped would give them extra teeth failed when it reached the Utah County Commissioner’s Office.

"We gotta find ways to build service centers around [the homeless], not just write tickets and say we’ll incarcerate them." Lee

“First and foremost there are so many elements to this problem,” said Bill Lee, Utah County Commissioner’s Office. “Just chasing this problem around doesn’t seem to work. We gotta find ways to build service centers around [the homeless], not just write tickets and say we’ll incarcerate them. I didn’t see that in their proposal.”

Along with the proposal not addressing ways to service the homeless, Nathan Irvine from the Utah County Commissioner’s Office also explained that the issue is more complex than just transient camping.

“When we think homelessness we only think Rio Grande and shooting up drugs and cardboard signs,” said Irvine. “We need to look at our ordinances and see whether we are giving our police officers and elected officials the right tools to address the homelessness issue.”

Despite the panel disagreeing on the proposal, most believed that the issue still needs a solution.

“What we need is a collective dialogue so we can provide the correct solution,’ said Irvine.

“It starts at this level. If they had done this in Salt Lake County and put something in place 15 years ago we wouldn’t be having this discussion,” said Chief Deputy Darin Durfey, Utah County Sheriff’s Office.

Read more on Provo and transient camping here and here.

Moving Forward

Inside Hughes’s “War Room” office across from Rio Grande last November, lawmakers met with Press announcing the launch of phase 3 of Operation Rio Grande, coined “dignity of work.”

As part of the phase, four employment councilors meet with homeless people one-on-one to assess employment readiness and needs. From those assessment, people will fall into one of three categories: those who may be addicted to drugs or have other issues preventing them from employment, those who need training, or those who are “work ready” and could start the next day.

Later that month, a dozen Road Home residents participated in a project with Okland Construction tearing down and replacing the old graffiti-covered fence.

“I will tell you of all the phases I’m most excited about, it’s phase three,” said Cox. “We all recognize that critical to overcoming homelessness, critical to overcoming addiction, critical to just living the American dream is the dignity of work.”

The overall goal of Operation Rio Grande was to get the homeless population ready for the three new resource centers set to open in June 2020 according to Hughes.

“Ultimately I just want the criminals, the people preying on the vulnerable to leave.” Hughes

“If we hadn’t gotten a handle on what was going on in Rio Grande, there would be so many people that we wouldn’t be able to accommodate them in the new resource centers. It’s harder for criminals to hide in smaller groups,” said Hughes. “Ultimately I just want the criminals, the people preying on the vulnerable to leave.”

Along with Operation Rio Grande, the state has an affordable housing shortage.

“This shortage is especially bad for those in “very low income” group, which means they are 30 percent of the area median income or lower, have a housing shortage of nearly 40,000 unites,” said Davis.

The Legislature combated this shortage with an incentive program for landlords in early 2017. In HB36 landlords will received reimbursement for any damages caused by tenants under the Housing Choice Voucher Program, with the goal of reducing financial risks for landlords and opening more housing to “very-low income” tenants.

Davis said that on top of Housing First, Utah recently implemented a coordinated-entry assessment approach. This means that whenever a person enters a shelter they will receive a personal evaluation as to asses their needs and find the quickest way to get them housing.

“We’ve been using a Housing First approach for more than 10 years. We will continue to focus on getting people into housing and then tackle other issues, as well,” said Davis.

Meanwhile Greg continues singing his self-proclaimed homeless anthem

“Signs” by Five Man Electric Band.

“Sign, sign, everywhere a sign

Blockin’ out the scenery, breakin’ my mind

Do this, don’t do that, can’t you read the sign?”

Draper Mayor's Fight

Earlier this year, another government official stepped up in hopes of changing the conversation surrounding homelessness Draper Mayor Troy Walker.

Walker’s announcement came as a shock after mayors in South Salt Lake and West Valley blasted Salt Lake County for choosing their cities for the two other sites.

“I really saw it is an opportunity to change the conversation,” said Walker. “Take it out of the negative realm and put a better face on it.”

Mayor Walker

Walker and Salt Lake County Mayor Ben McAdams, charged with finding the final site location, set up a town meeting to get community input on the decision.

What unfolded was four and a half hours of boos, screaming, and angry rebukes. Most residents fearing the center would bring crime and drugs into their neighborhoods. Others anger was focused on that they were only give a day to protest the proposal.

“It was probably one of the nastiest experiences in anything I’ve ever done. We never even got an opportunity to speak. We primarily were yelled at and ridiculed on multiple personal levels. I didn’t expect it,” said Walker.

After running nearly two hours over schedule, Walker turned to McAdams and rescinded the offer.

“We hadn’t made up our minds. Our goal was to take it to a political meeting and see what the input was like,” said Walker. “The input was resoundingly, “Hell no!” and I listened.”

“It was probably one of the nastiest experiences in anything I’ve ever done." Walker

Along with booing and screaming, many claimed Walker was personally gaining from the offer. Some even accused him of owning the property, others said he was doing it for the Utah Transit Authority.

Walker who had previous jobs where he was only one paycheck away from being homeless said that most everyone later apologized for what they had said to him at the meeting.

“They might not have agreed with me but they understood what I was trying to do,” said Walker.

In spite of going through the “nastiest experience,” Walker ran for Mayor again.

“My opponent [Michelle Weeks] in this last election used it as a great launching point for their campaign. They tried to use it for political gain,” said Walker. “I wasn’t trying to do it for political reasons. It was a stupid political move. If I was being a calculating politician I would have never brought it up.”

Despite his opponent’s moves, Walker beat Weeks and was re-elected this past November.

“I’m at least honest and I’m pretty straight up on what I believe and most people respect me for it,” said Walker.

Mormon Faith and Homelessness

Leaders across all platforms have collaborated in new ways these past few months in hopes of finding a solution for the state’s homeless population.

Religious leaders are some of those on the forefront of Utah’s battle against homelessness.

Welfare Square owned by the LDS church in Salt Lake provides food and services to those in need.

(LDS.org)

“Utah is definitely a religious state. They are a heavily involved state and the support the religious community gives trickles down,” said Davis. “The presence of religion plays a role in all the support the homeless receive in Utah.”

Roughly 82 percent of Utahans report being religious compared to the national percentage of 49, according to Spearling.

Of the 82 percent of Utahans who are religious, 72 percent are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Headquartered in Salt Lake City a few blocks from Rio Grande, the LDS church continually voices their concern and even donated $10 million to the cause last month, accompanying the $42 million donated to eight community and religious organizations in Salt Lake City already.

The money will go to the construction and development of transitional housing in Salt Lake as a response to state and local governments efforts to end homelessness through “Operation Rio Grande.”

“Homelessness affects all sectors of our communities,” said Bishop Gérald Caussé, Presiding Bishop of the Church, in a Mormon Newsroom press release. “We join hands and hearts with dozens of partners engaged in alleviating suffering in their respective communities, and in the process we point people towards greater self-reliance.”

“Homelessness is a tragic condition that afflicts individuals and even families in many places, including Utah." LDS Church in worldwide statement

In addition to the donation, the LDS church offered one of their properties as a location for one of the three new resource centers being built to replace The Road Home.

“We continue to look for ways to support this effort,” the church said in a statement.

In a statement released in April by the First Presidency of the LDS church, the church applauded government, community, and civic leaders tackling the homeless issue and encouraged members to help in a “Christlike way.”

“Homelessness is a tragic condition that afflicts individuals and even families in many places, including Utah. The causes are varied, and solutions are often difficult, but whether homelessness stems from conflict, poverty, mental illness, addiction or other sources, our response to those in need defines us as individuals and communities,” said the church.

Despite the church’s stance on homelessness, many religious Draper residents participated in the controversial meeting with Walker only week prior to the statement’s release.

As the Draper incident and statement illustrate religious status doesn’t always determine the likelihood of active participation in programs that help the homeless cause.

Nevertheless, Utah faith-based institutions are continually applauded for their support in solving homelessness.

“Religious organizations and religious people in Utah play a crucial role in the support homeless people receive in the Utah community,” said Noll.

Other Solutions Across U.S.

While Utah continues Operation Rio Grande, other states are taking unique approaches to end homelessness in their communities?

In recent months, authorities have declared homeless “states of emergency” in Hawaii, Seattle, Los Angeles, and Portland, Oregon. Other locales have taken controversial steps to deal with the crisis on their streets: designating parking lots where people can sleep in their cars and building temporary housing out of repurposed shipping containers.

Another reason for optimism among advocates is that government agencies, service providers, and community groups are getting smarter in trying to solve the problem. Utah’s Operation Rio Grande, no matter how drastic, is pushing the state towards change in Salt Lake.