“The community around the river helps make it a good river as well,” Zicha said. “There are so many people here that enjoy the river or the outdoors in general, so they’re supportive of people that want to come in and use it.”

For anglers in the Heber Valley that rely on the Provo River, it means more than just a weekend hobby. It means having something to share with anglers from around the world. And according to Zicha, they’ll continue to defend it.

“There are a lot of different ways that the folks in my business interact in a positive way with the water itself and the animals that go along with that,” Zicha said. “I don’t see that changing here in this area, because I know the people and the passion behind it.”

Enlarge

Sebastian Meyer (Google Earth)

Access to the River

The middle Provo’s success sets an example for the balancing act of preservation and recreation, and its evident in the community’s enthusiasm. But while anglers enjoy virtually complete access to this section, access on other stretches of the Provo and other public water in Utah is not a guarantee.

Utah water access laws have become a thorny issue in recent years. In 2008, a court case decided by the Utah Supreme Court ruled that because the public has the right to public waters such as rivers, they have the right to touch adjacent private land next to and under the water in a reasonable way if they are recreating.

However in 2010, the Utah state government passed a bill that effectively reversed this decision, banning the public from any contact, even incidental, with private property while recreating on public waters.

The current law states that if an angler wants to fish public water that runs through or over private land, they must first get permission from the landowner. However, tubers, rafters, or fisherman on inflatables are allowed to recreate on the same water without permission so long as they don’t make any contact with the ground beneath the water or the banks of the river.

For Chris Barkey, this decision was unacceptable. Barkey, along with some friends, started the Utah Stream Access Coalition, an organization designed “to promote and assist in all aspects of securing and maintaining public access to, and lawful use of, Utah’s public waters and streambeds,” according to their website.

“This is strictly a use issue,” Barkey said. “I don’t like the word ‘access’ because this is about being able to use a resource that the constitution of this state says the public owns.”

Rizek Housari, a member of BYU’s fly fishing club, said some landowners take this idea to the extreme.

“Some land owners will create additional barriers that go down into the stream bed that prevent public access users from entering,” Housari said. “This includes fence, barbed wire, signs, etc. If the stream bed is deemed public use by the government, then any infringement is illegal.”

Barkey argues that the coalition believes liability lies with the user for properly using the land and not with the landowner. The coalition supports tighter regulation of trespassing and littering laws, as that would clamp down on those who do not treat the land with appropriate care, who, according to Barkey, are usually not anglers.

“The preservation of the Provo River specifically, I think is something that needs to be really addressed,” Barkey said. “That summer-time user, the floaters, the tubers, really need to have their hands slapped and be shown you can’t just leave all your trash or lose your flip-flops and not retrieve them.”

While some progress has been made, like a recent case that ruled a mile-long stretch of the Weber River was navigable and therefore publicly accessible, Barkey said there is still a long way to go.

“That one mile stretch will grow pretty rapidly,” Barkey said. “That will grow into the Bear River from the Forest Service to the Wyoming border, the Logan River, the Black Fork, the Ogden River.”

However, Barkey said the Provo is not a guarantee.

“I’d pump the brakes [on the Provo River],” Barkey said. “None of that has been done yet, but it will be over time. It’s a matter of being informed and being patient. I’ve been fighting this for almost nine years now, and the patience has to be there by the public.”

The coalition is currently fighting a court case concerning public access on the Provo River. The coalition contends that the current Utah law prohibiting recreation-seekers from touching private land within reason violates the constitution of the state.

Restoring the River

Part of the reason for Heber Valley’s enthusiasm for the Provo River is likely due to the massive restoration project that completely redesigned the section of the Provo that runs through the valley.

The restoration process began as an effort to repair any damage done to the natural river as a result of years of agricultural, industrial, or otherwise human-made harm.

Restoring a river to its natural state is not an easy operation. But Erin Jones, a PhD student specializing in water quality and aquatic microbial ecology at BYU, said that the Provo River Restoration Project (PRRP) is one of the best restoration efforts she’s seen.

“All of the money for the state of Utah, really, for all the water projects went into restoring the middle Provo and doing it correctly”, Jones said. “In stream restoration, it’s viewed as one of the best success projects by far.”

Restoring the Provo River included removing 10 diversion dams, creating over 50,000 feet of new river side channels, and reshaping the main channel of the river to include more bends. The project cost upwards of $50 million, federal money sent out by Congress.

What makes this river restoration project stand out, according to Jones, is the attention payed to the entire environment surrounding the river, not just the stream itself.

“The return of wildlife, of native vegetation, birds, amphibians. The numbers are pretty astonishing,” Jones said. “The attention to detail they took to put in native grasses, and to build backwater habitats and wetlands that would periodically flood… Those are the kinds of things that really made a difference.”

Running through the Heber Valley, the river was used as a water source by local farmers. Over the years, the farmers had dyked and transformed the river to better fit their needs as a water source. The natural habitat of local wildlife had been disrupted, and with the additions of the Jordanelle and Deer Creek dams, much of the habitat was unrecognizable.

Starting in the 1980s, the federal government funded a major restoration project for the Provo River. But in order for the government to restore the river, they had to gain access to the land they were planning to work on. The Utah Reclamation and Mitigation Conservation Commission (URMCC) began a “pilot project” on a mile-long stretch of land beneath Jordanelle Dam already in federal ownership, according to Mark Holden, executive director of the URMCC.

In 1990, they set to work purchasing or leasing land from landowners who lived on the river. Holden said some landowners were keen to contribute to the project.

“We also had landowners come to us, saying ‘Our land is going to need to be acquired, and we’d rather you buy it now”, Holden said. “We absolutely needed the land we were going to work on for the next segment of work for that next summer.”

The URMCC worked on a stretch-by-stretch basis, rebuilding the land they had while waiting to acquire more. For nine years, the PRRP jumped around the middle Provo, restoring stretches of river to a quasi-natural state, and the project was completed in 2008.

Impact on Wildlife

The restoration of the river was not just a favor for local anglers. Primarily, the PRRP sought to restore the natural habitat of the wildlife that lived in and around the river, which is a lot more than fish.

Chris Crockett, an aquatic biologist with the Utah Division of Natural Resources, specializes in native amphibian species. Some of his first experiences with the Provo River were work on the habitat of the Columbia spotted frog, a species on Utah’s Sensitive Species List.

He said the PRRP was more than just a river restoration, as it greatly benefitted all the wildlife that lives in the riparian zone and surrounding wetlands.

“They helped create a lot of that Columbia spotted frog habitat,” Crockett said. “It was there to begin with, but degraded a lot through the years.”

Crockett mentioned that although Deer Creek Reservoir and Jordanelle Reservoir are quite popular for recreation and utility, they created big problems for the conservation of the wildlife and wildland they displaces

“A lot of people don’t really think about the fact that Deer Creek Reservoir and Jordanelle Reservoir, while we love them,” Crockett said. “They flooded a whole lot of riparian floodplain habitat that did provide a lot of different styles of habitat for things like waterfowl, birds, and frogs.”

While the PRRP targeted the middle Provo, the lower Provo has not seen the same kinds of restoration efforts. Despite being arguably the most utilized for recreation, it has not seen any rebuilding efforts on par with those of the middle Provo.

One possible reason is the infrastructure preventing major work projects. The lower Provo winds through the tight Provo Canyon, with high canyon walls on one side and a highway on the other. These large features constrict the amount of restoration possible, as there is little room to expand the river and its banks.

“I wouldn’t say it’s a lack of interest or even a lack of need,” Crockett said. “It’s just not as conducive to restoration.”

But there is one section of the lower Provo that is desperately in need of restoration, and there are plans in place to save a peculiar species of fish that lives there.

The June Sucker

The Provo River and Utah Lake are the only home of a unique fish called the June sucker. While it used to thrive in Utah Lake, the June sucker is now critically endangered. Competition from nonnative species like carp have left the June sucker fighting a losing battle to survive in its native waters.

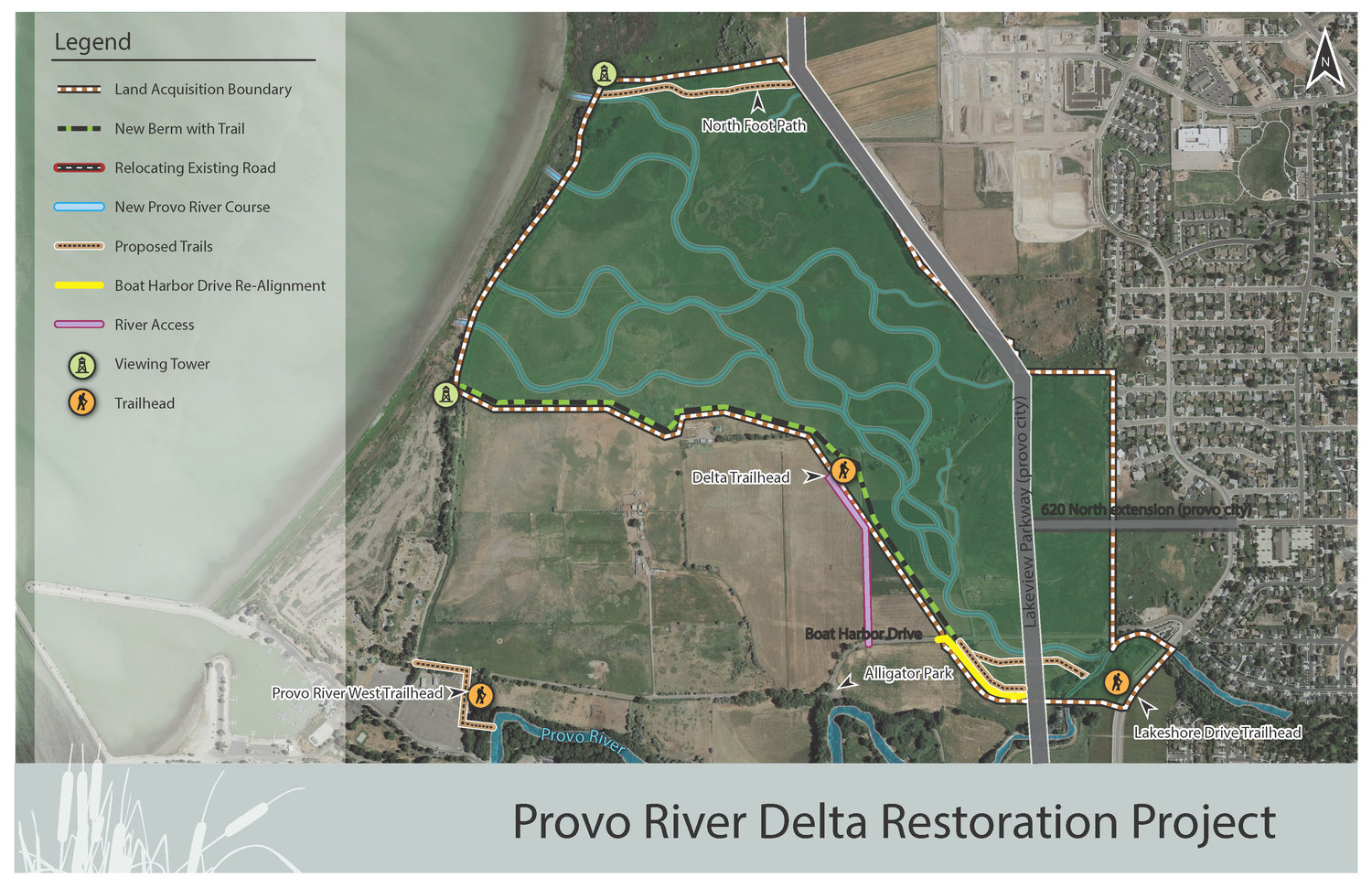

In an effort to combat this, the URMCC has proposed a new project called the Provo River Delta Restoration Project (PRDRP) that focuses solely on the preservation of critical June sucker habitat. The PRDRP would completely revamp the section of the Provo River that flows into Utah Lake, making it much more conducive to June sucker survival and expansion.

The proposed map for the Provo River Delta Restoration Project. (Courtesy of URMCC)

“The June sucker spend most of the year in Utah Lake,” Dale Fonken said. “In the late spring and early summer, they swim up the tributaries and spawn, and the Provo River river is definitely where we see the vast majority of the suckers from Utah Lake.”

Dale Fonken is a June sucker biologist for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. He said like the original Provo River Restoration Project, the Provo River Delta Restoration Project will restore the river to something closer to its original, natural delta, something much more comfortable for the June sucker.

“Where the river entered the lake, historically it kind of fanned out into dozens of braided channels,” Fonken said. “Basically, it provided complex habitat for the larvae that were just spawned by the adult June suckers, and provided a habitat for them to settle down in a place where they were free from predators.”

In his mind, the project is hitting two birds with one stone. Like a lot of the restoration projects, though the primary goal is conservation, recreation is going to see some progress as well.

“I think conserving native species is good for everyone,” Fonken said. “It’s good for native species and its good for recreation as well. I think people don’t realize that the money being spent to restore the lower Provo River because of the June sucker is going to make the river better for everyone.”

The project to restore the delta indicates a future for restoration on the Provo River. The success of previous restoration projects from environmental and recreational standpoints show a strong case for continued preservation of the Provo. While the balance between recreation and preservation continues to be argued, preservationists argue the future is in their favor.