The theory of creation-evolutionism is a hard topic to grasp for some who are religious because of its seeming threat to their faith.

The BYU biology department hosted a Reconcile Evolution Conference with 18 different religious universities to create reconciliation modules and videos for professors across the nation about why Christian creationism and the theory of evolution can fit together.

Participants from some of the universities stated their concerns — and even distress — with taking these specific ideas and videos back to their university for fear of either losing their job, losing donors or the having students feel that their faith is at risk.

Physicist, scholar and author Karl Giberson, who has been at the forefront of the creation-evolutionism debate, said some in attendance come from institutions who financially rely on those donations, and there are many smaller institutions in the same position.

Giberson said many of the professors at the conference are unsure of how much information they can talk about at their institution because evolution and creationism are so controversial.

“They can’t afford to tick off donors,” Giberson said. “Many of (these professors) are embedded in politically charged institutions where they have to tread very lightly as they make progress.”

One of the universities stated though evolution is part of the curriculum, there is still a history of people from their institution who don’t like the word. Giberson said this is the case at many of these institutions.

“There is a concern that the word evolution and the sorts of things we talk about (at this conference) will raise flags with these people, who will then report to the school administrators their concerns and would cause trouble,” a representative said. “And universities like to avoid trouble, especially when it involves money.”

Aside from the fear of academia and donors, some universities were concerned about students pushing back on the subject or complaints about this happening at a religious institution.

A theologian at the conference questioned if the spiritual payoff for pushing something like evolution with a religious student body, a topic that might challenge their faith, is worth it. He said it is a good thing to push evolution because it encourages thinking for spiritual, not just scientific, reasons.

Giberson explained this conference is a preliminary conversation. The constructive data from BYU professor Jamie Jensen has shown that this reconciliation teaching has been effective; which will hopefully give confidence to these professors to test these modules at their own institutions.

“We have got to make space — theological space — for students to be able to get into the conversation,” Giberson said. “They can’t enter the conversation if they think that you are on a slippery slope to perdition as soon as you start saying you believe in evolution.”

BYU is also no stranger to this debate. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints is neutral about evolution, but according to BYU biology professor William Bradshaw, members have had a more negative outlook on the matter.

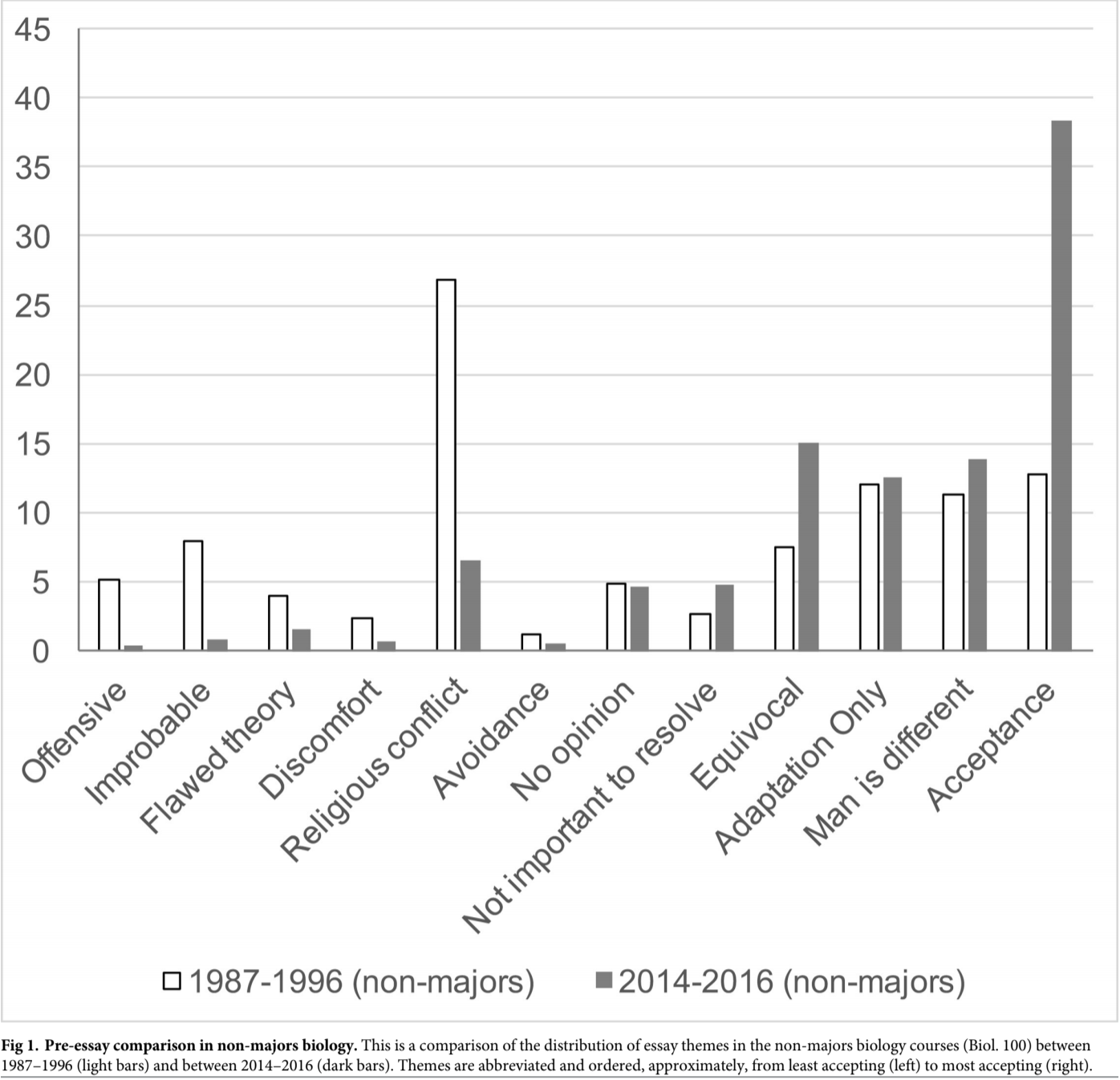

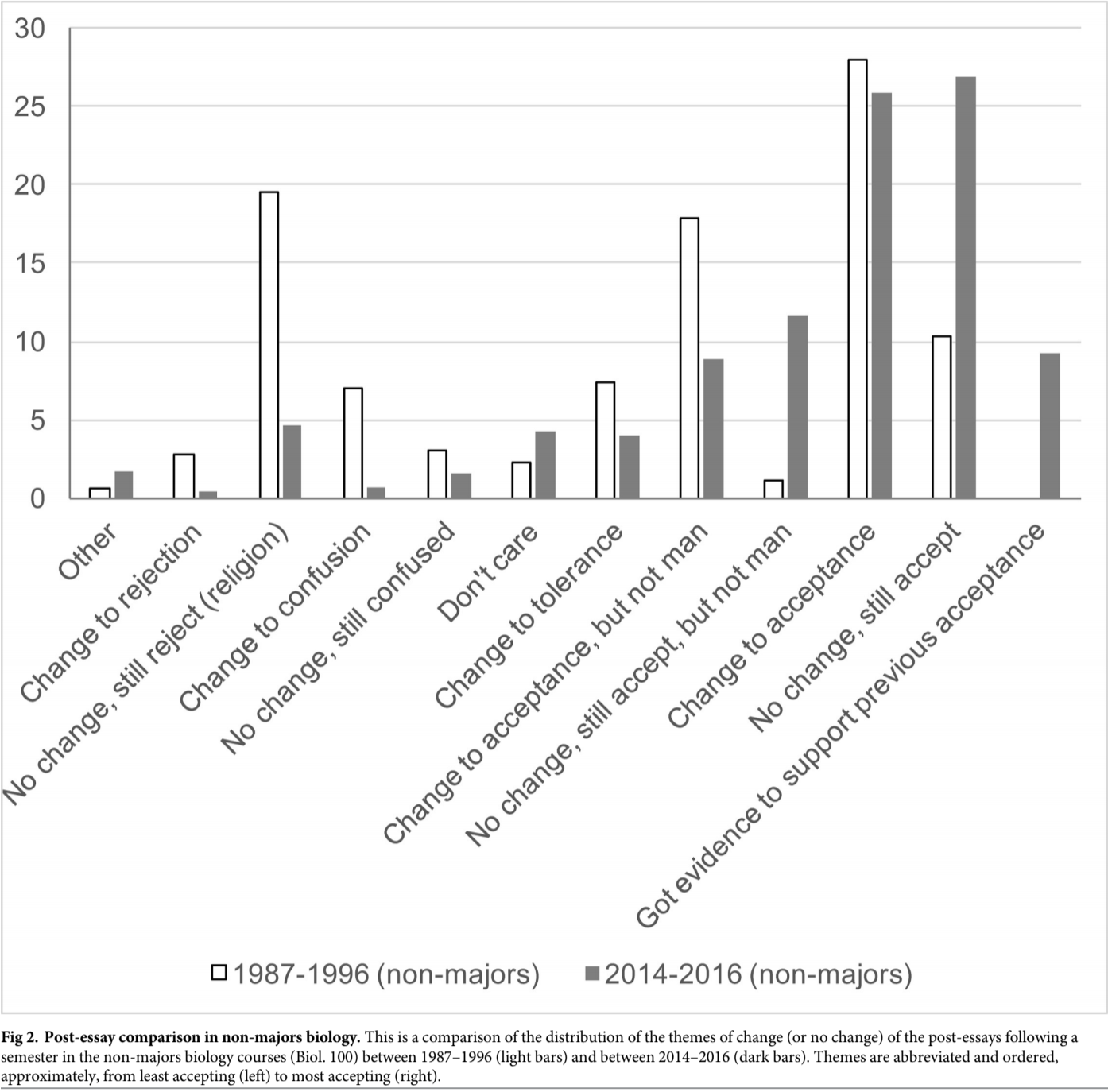

Back in the ’80s, Bradshaw began reconciliation testing at the beginning and end of each semester. He said students were more apprehensive in accepting evolution because of the negative views from sources around them.

“During this time, there would be BYU students who would go to their religion class and have their teacher strongly condemn evolution,” Bradshaw said. “And then they would come to Biology 100 and be presented with the notion that evolution was true, but that it was not an enemy to their religious faith.”

The acceptance of reconciliation between evolution and religion have increased since that time.

Jensen said she began giving a similar test at the beginning and end of each semester in 2014 and has seen a change in the data from her classes today and Bradshaw’s classes. The graphs demonstrate the differences between the two time periods and how there is a dramatic shift between the pre-essay and post-essay beliefs.

According to BYU biology professor Seth Bybee, since 2016, the BYU biology department has held three evolution conferences and has had full support from its administration.

President Kevin J Worthen sat in on the conference in 2017 and Vice President John Rosenberg welcomed the universities at this year’s conference.

Bybee said the university supports the teaching of theist evolution but emphasized that the Church has no official stance. Since March, an evolution exhibit has been open in the Bean Museum explaining the theory of evolution.

Jensen said this conference will try to make teaching the theories of evolution and creationism easier for religious and agnostic professors. A representative said people know about this conflict of creation-evolutionism but it’s a hard conversation to have. Giberson said this is a stepping stone to create conversation and understanding.

“Conferences like this can give people hope and see that they are not in this fight all by themselves,” Giberson said.