BYU junior Kim Morgan lived at Heritage Halls as a freshman in a ward where all the 18-year-old young men and most of the young women were preparing to serve missions for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“I had never considered serving a mission before coming to BYU — in fact, I actively did not want to serve a mission,” she said. “Being around so many people preparing to serve though caused me to have an early midlife crisis.”

Social pressure to serve a full-time mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is a familiar feeling for many women at BYU, according to Morgan, an elementary education major from Lake Stevens, Washington.

“That was the hot topic question that was asked so very often in my ward — ‘Are you preparing to serve a mission?’” Morgan said. “When I’d tell people no, they’d ask, ‘Why not?’”

In October 2012, then-Church President Thomas S. Monson made an announcement that lowered the mission age requirement for women from 21 years old to 19. This encouraged a surge of women to serve a mission.

Heber City resident Liz Heywood served a mission at the Nauvoo Visitor Center from May 2008 to November 2009 and subsequently taught at the Missionary Training Center. She said she did not feel external pressure to serve.

“Twenty years or so ago, it felt like missionary service among girls was regarded as the backup plan for those who weren’t married,” Heywood said.

Since the age change, female full-time missionary service has increased, especially at BYU.

Before the age change, Heywood said many women were either engaged, married or deeply consumed in finishing their undergraduate degree, making missionary service especially difficult.

According to the Church’s 2012 statistical report, there were 58,990 full-time missionaries in the field that year. In 2013, following the age change, the number increased to 83,035. Approximately 64% were elders and 28% were sisters, with seniors making up the remaining eight percent.

Since the initial spike in female service, the Church-wide number has returned to near what it had been before the change. In 2018, according to the statistical report, there were 65,137 full-time missionaries in the field.

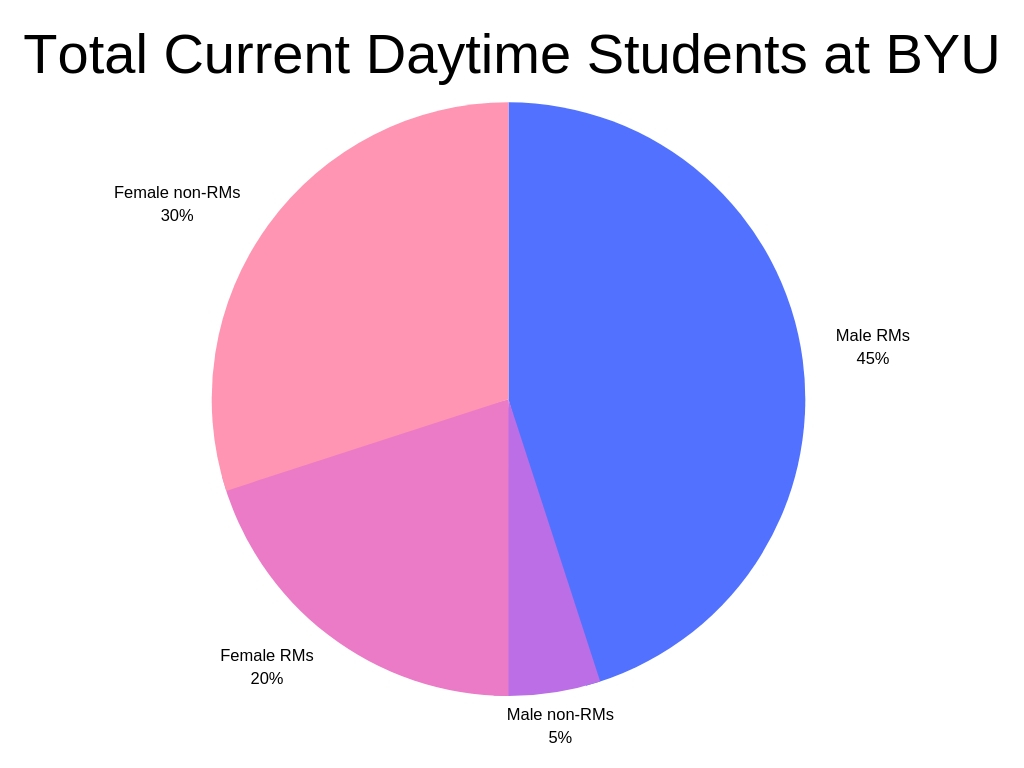

However, at BYU, the number of female missionaries is still increasing. In 2018, 52% of the female BYU graduates were returned missionaries, making it the first year with a majority of female graduates being returned missionaries. Previously, the numbers were 45% in 2017 and 34% in 2016. This academic year, according to BYU Facts and Figures, 66% of total daytime students have served missions.

One result of increased missionary service among BYU is that women can feel increased social pressure to serve missions.

“It was an unintended but foreseen consequence of lowering the mission age,” Michael Goodman, an associate professor in the BYU Church History department, said. “At the time of the announcement, President Monson explicitly stated that sisters are not under the same mandate to serve as are the young men, but that has not completely removed the public and, at times, private pressure some sisters face in the decision-making process.”

Goodman said the age change has inadvertently caused “unhealthy expectations.”

“Culturally, if we are not careful, it will become an expectation for them to serve and that is not what was intended,” Goodman said.

Some women at BYU who chose to not serve missions feel like return missionaries look down on them.

“At BYU, there is a tendency to ask people if they served a mission, but if they say no, a lot of people will say things like, ‘Oh, that’s OK,’ or, ‘Hey, that’s great too,’” Dallin Christensen, a BYU sophomore who served a mission in Tahiti, said. “Girls know that it’s OK. That’s why they didn’t do it. It’s a choice for them.”

The BYU dating scene adds additional pressure, as some young men choose to date only returned missionaries, according to Morgan.

Morgan said she feels “the idea that guys only want to date girls who have served missions — something that has been said to me and my roommates on many, many occasions — is wrong.”

According to Christensen, sometimes “return missionary” is added to the list of qualities a young man wants in a future spouse.

“That infuriates me because, in order to date him, a girl has to do something that the Lord has declared optional, so there is this underlying pressure for girls to serve in order to appear more attractive or mature,” Christensen said. “I’m not a girl, but I imagine that it can be intimidating or annoying when she’s with return missionaries because of the stigma that we’ve created.”

Christensen said he believes that serving a mission doesn’t necessarily make someone more qualified or mature.

“There are people that really changed on a mission, and there are those who wasted time on a mission,” he said. “Just because a girl doesn’t serve a mission doesn’t mean that she is less mature or isn’t having experiences that are helping her to grow and change.”

Morgan said she believes missions are “wonderful” and teach valuable lessons, but they are not required for women.

“If a girl wants to serve — great! If she doesn’t — that’s also great! It is absolutely wrong for guys to base girls’ spirituality and attractiveness on whether they have served a mission or not,” she said.

Even without the atmosphere prevalent at BYU, the pressure for women to serve missions still exists Church-wide, although differently.

Church member Abigail Whiting, a sophomore from Tucson studying English education at the University of Wyoming, said she did face pressure to serve a mission, but not from her peers.

“I feel like it was less of a community pressure and more of a personal pressure,” Whiting said. “I had always wanted to serve a mission, but the people around me actually seemed like looking for marriage was more of a priority.”

Ultimately, she chose to get married rather than serve a mission and said she faces feelings of inferiority as a result.

“This may be something completely internalized,” she said. “I don’t think outside influences actually think I’m a lesser person because I didn’t serve.”

Joe Alldredge, a bishop in the Provo Young Single Adult 3rd Stake, also said he thinks the pressure is more self-inflicted.

“Pressure seems to be more self-imposed when (young women) are in a Sunday School class or Relief Society and they keep hearing RMs say, ‘On my mission …’” Alldredge said.

Still, Whiting said she thinks return missionary women are seen as more mature and experienced in spiritual matters. In her experience, women in singles wards were “snatched up and married off” quickly after their return.

“Some of my beliefs around serving a mission turned towards thinking that it would be one of those things that made me more appealing to people in my dating pool and the local leaders in the Church,” she said.

Joseph Furniss from Murray, Utah did not serve a mission. In his first year as a biology/pre-med major at Utah Valley University, he spoke from a broader perspective. “For many of us, I think we have this idea that a mission, because it is such a unique experience and an important theme in the scriptures, is the only way in which anyone can have any meaningful growth as a person both spiritually and mentally.”

He said he believes Church culture emphasizes the idea that right after high school, a woman can now marry or serve a mission.

“Even though a mission is not considered mandatory for them after graduating, the first questions that they are asked at a family get-together is, ‘Are you dating anyone?’ or, ‘Are you planning to go on a mission?’” he said.

The pressure to serve does not apply only to women. Furniss prepared to serve a mission but was respectfully excused by the Church, and he said it has been hard to navigate the mission-centered culture of the Church as one who hasn’t served a mission.

“Almost every lesson in Young Men’s is either starts with or ends with, ‘On your missions, this will be really important for you to know,’ or something similar,” he said. “I think for me, especially, I was in the mindset that if a young man didn’t serve a mission there was something the matter with him.”

Even though many negative consequences accompany the pressure placed on young members of the Church to serve missions, the pressure can also be positive, Morgan said.

This pressure led Morgan to attend an informational meeting about performance missions in Nauvoo, and she considers her summer as a Young Performing Missionary playing the trombone the best summer of her life.

“In dating situations, returned missionaries need to stop basing girls on whether or not they served a mission,” Morgan said. “But in other situations, it can spark a real journey for each girl to go through, to decide whether or not she truly wants to go serve a mission.”

Alisa Buchanan, a junior and French major from Frisco, Texas, was another who said the pressure was a blessing. Buchanan served in the France Paris Mission from 2016-17 and attributes the pressure with accelerating her decision to serve — a decision she said was one of the best decisions she has ever made.

“I think that the word pressure denotes a negative pressure, but for me, the pressure was very positive,” Buchanan said. “I am well aware that a positive experience with the cultural pressure at BYU is not the norm.”

In a 2016 Face to Face event with young single adults, Elder Jeffrey R. Holland said he remembered that, at the time of the age change, President Monson “was adamant that we were not going to create a second-class citizenship for young women who did not serve a mission.”

Elder Holland said, “If a young man doesn’t go, that does not preclude him from our association and admiration and his priesthood service and his loyalty and love of the Lord in the future in the Church. That ought to be true for young men as well as young women, but adamantly for young women.”

According to Elder Holland, in lowering the age requirement, President Monson did not intend for all young women to serve full-time missions. Elder Holland said that when the age change was announced, the percentage of missionaries who were female “went from something like 8 or 10 or 12% to 30 or 35%” and he acknowledged the increase has had a positive impact on the growth of the Church.

“But we do not want anyone feeling inadequate or left out or undignified or tarnished because she did not choose to serve a mission,” Elder Holland said.

Furniss said he thinks Church members often jump to conclusions in regard to members who do not serve.

“I think it’s important to remember that there isn’t an LDS mold. The Atonement wasn’t made for a collective ‘we,’ but for each individual of the whole,” he said. “This is how we need to think of each of our brothers and sisters, as well as ourselves.”