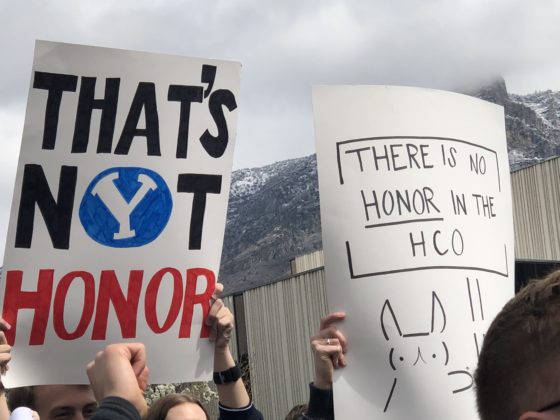

Hundreds of BYU students and alumni protested Honor Code Office procedures earlier today in a demonstration at the Cougar Quad on the BYU campus.

Protestors chanted “Students made it, we can change it,” sang Primary songs and listened to students and alumni speak about their negative experiences with the Honor Code Office. Materials were also available for students to write letters to the office.

The protest coincided with GLSEN’s nationwide Day of Silence for LGBTQ students. Protestors took a moment of silence at 1 p.m. to honor LGBTQ students who have died.

The students conducted themselves in a peaceful, respectful manner. Speakers refrained from using expletives and the overall atmosphere was calm but energized. A number of onlookers (who were encouraged several times by the protestors to “come on down!”) and counter-protestors stood on a balcony overlooking the quad, occasionally chiming in.

“If you don’t like the Honor Code, go to a different school,” one individual shouted during the moment of silence.

The Restore Honor movement planned the demonstration in response to the alleged mistreatment of students by the Honor Code Office, as exposed by the Honor Code Stories Instagram page, which has more than 34,000 followers. Restore Honor, which was organized by freshman Grant Frazier, is calling for more accountability, protection, advocacy and empowerment in the Honor Code Office.

“Here at the university, we believe in the Atonement, and we want to show the Honor Code Office that,” Frazier said.

Restore Honor social media manager Evan Jones said he feels very strongly about improving BYU by updating the Honor Code policy.

“At this specific event today, I hope to garner excitement and to raise awareness for students here on campus,” Jones said.

According to Jones, the group’s short-term goal is to see policy change, and its long-term goal is a shift in culture.

“We hope for change. But we can’t just hope. We have to show up to these events. We have to sign our names on the letters. We need to keep advocating,” Jones said.

Sidney Draughon, the BYU alumna who created the Honor Code Stories Instagram account, flew to Utah from New York to attend the event.

“I love this campus, but there is a lack of love and a little bit of disconnect right now, and we’re just trying to pull that together,” Draughon said.

Draughon said she had experiences with the Honor Code Office during her freshman and senior years at BYU. She said being repentant “wasn’t ever good enough” for the office.

“We just want more love on campus,” Draughon said. “We want people to feel like they can use the Atonement on campus, and they can find Christ on this campus, and that everyone feels like they are welcome and included here.”

Several students, alumni and supporters spoke to the protestors following the moment of silence. They discussed their experiences with the Honor Code Office, the fear they felt of being punished and lent support to those struggling at the university.

Former BYU football player Derik Stevenson, who was suspended from the university in 1997 for firing a gun into the air during a fight, spoke about suffering from pain pill addiction as a student athlete. He said at 23 years old, he felt terrified to talk to anybody about his struggle.

“So at 23 years old, being ashamed that I realized that I was an addict, decided to just stay silent. That shame and that guilt that is bred in our culture, just built up in me,” he said.

Stevenson said the fear he felt ultimately led to suffering from his addiction for a decade, and cost him his marriage and custody of his children. He said he wished he had felt more comfortable reaching out for help, rather than fearing punishment from the Honor Code Office.

“I feel like the worry of the punishment the Honor Code would hand down kept me from being honest,” he said. “It was spiritually damaging to me, to not feel like I was in a place where I could be honest.”

Stevenson said he has since started speaking out and questioning why BYU students feel afraid to be honest about their mistakes. “Honesty is key for anybody that wants to spiritually get better,” he said.

Stevenson said he had spoken to BYU football team and coaches, who sent their love and support to the protestors.

Ron Weaver III, a black BYU student, said he had been called into the Honor Code office for dying his hair blonde. While speaking to an honor code counselor, Weaver said the counselor told him the hair color “was unnatural” for him.

He said even after his mother encouraged him to “swallow his pride” and dye his hair black again. However, Weaver was later told by his counselor the way his hair grows was “unprofessional.” In response, Weaver left the office and received a call 30 minutes later that his hair had been approved.

“I walked out of the office and kept fighting the case. I didn’t sign my rights away at all,” he said, referring to the priest/parishioner release form students are encouraged — but not required — by the Honor Code Office to sign.

Weaver encouraged students to follow his example and fight their case respectfully. He said the office and how they treat students needs to change.

“You have the right to fight back but do it in the right manner. You can’t be angry or use malicious words,” he said. “You have to fight back as a respectful human and if you get disrespected you don’t have to stand there and take it.”

BYU alum Addison Jenkins said the language of the Honor Code previously changed in 2007 to better accommodate LGBTQ students at the university. He said at the time students could be disciplined simply for coming out as gay. After students advocated for change, the university changed the Honor Code within two weeks.

“We can change the Honor Code again,” Jenkins said. “It was started by students … We want it to be honorable. We want this to be an honorable school.”

According to Restore Honor’s Twitter account, the university sanctioned the protest.

BIG UPDATE: here is our official flyer with everything you need to know about our peaceful, BYU-sanctioned demonstration this Friday!! pic.twitter.com/lTpUaUH4ge

— Restore Honor BYU (@restorehonorbyu) April 11, 2019

A change.org petition calling for the Honor Code to be updated is also sitting at over 22,000 signatures. The petition asks that the Honor Code is updated to be in-line with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ modern standards.

“As a church that has Christ at the center of it, its school should be loving and accepting of those that meet its rigorous academic qualifications while understanding that not everyone has the same moral, health and grooming standards,” the petition reads.

The petition also advocated for self-reporting standards based on Church teachings regarding criminal activity, premarital sex, substance use or cheating.

The protest has received extensive media attention, including from national publications such as the Associated Press and Newsweek.

University spokeswoman Carri Jenkins emailed a statement in response to the demonstration this morning.

“Our goal has been and will continue to be to help our students succeed at BYU,” Jenkins said. “The students we have met with are committed to the Honor Code and ongoing dialogue, which we believe will lead to a better understanding of how the Honor Code Office can best serve our students.”