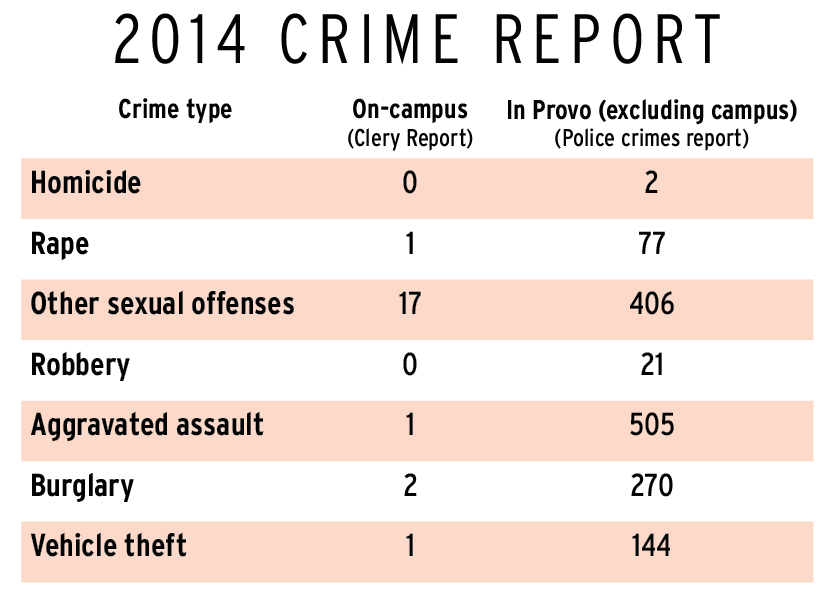

BYU reports an exceptionally low number of campus crimes every year, in a federally mandated campus safety report, and was most recently ranked the safest campus in the U.S. by Business Insider.

But the picture is incomplete because BYU and many other universities only report crimes committed on campus and at on-campus housing sites. Crimes involving students off campus or in off-campus student housing are not included.

The federal Clery Act, named after Jeanne Clery, who was raped and murdered in her college dorm at Lehigh University in 1986, mandates the annual report, overseen by the U.S. Department of Education.

The act requires colleges to report murder, manslaughter, sex offenses, robbery, assault, burglary, vehicle theft, larceny and arson committed in locations schools control.

Crimes included in this annual report are a combination of offenses reported to each college police department and other on-campus services, such as counseling and women’s services. Anything that goes unreported also goes unrecorded.

Cleary-reportable “index” crimes include murder, non-negligent manslaughter, forcible rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny (theft) and motor vehicle theft.

According to the national Crime in Utah Report, more than 2,900 forcible sex offenses were reported in 2013. Their most recent 2014 report indicates almost 88,000 index crimes were reported, which was a 5 percent decrease. However, rape increased by almost eight percent. Utah isn’t the only state to see such an increase.

BYU’s most recent security report lists 21 forcible sex offenses between 2013 and 2014, including one rape.

The Department of Education’s Handbook for Campus Safety and Security Reporting defines reporting requirements and says colleges must include crimes that occur “on campus, public property within or immediately adjacent to the campus, and in or on non-campus buildings or property that your institution owns or controls.”

Third-party contracted housing can be considered a “non-campus” location the school controls, if its owners have a written agreement with an institution to provide student housing, according to the handbook.

The Daily Universe sent a copy of a BYU student housing contract to the U.S. Department of Education and asked whether contract language gives BYU “control” over off-campus housing.

“The contract that you attached to your email appears to establish a written agreement between BYU and a third party to provide student housing, thereby giving BYU control of the space specified in the agreement,” states the response from the Department of Education help desk.

However, BYU and many other schools interpret Clery reporting language differently.

“In determining whether to include crime statistics from certain properties in an annual security report, schools maintain some discretion, and two important considerations are ownership of property and control of the physical space,” said BYU attorney Sarah Campbell.

Campbell said “control” was not defined in the law, and one must analyze BYU’s “extent of control, reservation of space and right of access.”

(Hover and click on the box in the left-hand-corner to see the key)

BYU’s contract with off-campus housing stipulates that only students attending UVU, BYU and other vocational colleges can live at contracted apartment complexes. If non-students attend an LDS institute class, they do not have to attend one of the specified schools to live in contracted housing. Other language in the Off-Campus Housing Handbook further muddies the water on whether BYU “controls” contracted off-campus housing.

“I think it is relatively uncommon that colleges own or control housing units that are not located on campus-owned property,” said Frank LoMonte, executive director of the Student Press Law Center. “Normally, if housing is not physically located on the campus, it’s an entirely private apartment building and thus beyond the reach of Clery.”

LoMonte said he wasn’t aware of any problems with “under-counting” crimes at off-campus housing. Yet student news stories from campuses around the country are regularly publishing stories about issues regarding compliance, or lack there of, with the Clery Act.

Emma Fried, a student reporter at Lehigh where the Clery story began, wrote about the varying interpretation for the Clery Act, specifically discussing its off-campus housing.

“By not including all students living off-campus in their crime reports, Lehigh is portraying only a small portion of the crimes in an area where a large percentage of students live,” Fried said.

Provo Police public information officer Nisha Henderson said numerous BYU students are involved in its police reports in some way. She could not estimate how much the Clery report would change if it included off-campus crimes, only that numbers of reported index crimes would rise if BYU included off-campus housing.

“BYU doesn’t control (off-campus housing).” University Police Lt. Aaron Rhoades said. “All they do is (say) ‘You abide by these rules or we won’t let our students live there.'”

The definition of control is not the only disconnect between the Clery report and a complete picture of crimes committed against the campus community.

Rhoades said Provo Police are not required to track and record the specific crimes statistics required by Clery. This would make it difficult for University Police to obtain the data they would need to include off-campus contracted housing in Clery. To accommodate BYU’s need for specific crime statistics, Provo police would have to change the way they track crime altogether.

Including off-campus housing crime reports would require Provo to keep separate data about the specific crimes that took place at both on- and off-campus housing. This is not a normal thing for city police to do, as generally their data is tracked city wide.

Under-reporting is also an issue, especially with sex crimes.

“We know things are happening on campus, but (students) are not coming forth,” said University Police Sgt. Elle Martin, who is responsible for crime prevention efforts at BYU. “It’s heartbreaking, and I want that to change so bad.”

Lauren Barnes, a BYU assistant clinical professor and marriage and family therapist, said under-reporting is evident in the annual safety report. She said other therapists have helped students report forcible sex offenses, but some students don’t feel comfortable reporting the crime to higher authority. “They’re usually pretty hesitant because they think they’ll get in trouble with the Honor Code Office,” Barnes said.

Barnes referred to BYU’s culture as an “interesting phenomenon,” which might relate directly to how people treat sex offenses on campus.

“I don’t know if it’s actually safer compared to other schools, but I think BYU’s culture might make it more difficult for people to be honest,” Barnes said. “I’ve even seen people claim rape when it was a consensual act, because they’re scared they might get kicked out of school.”