People are often concerned to learn Terance McCray grew up in Oakland, California and are intrigued by the city’s infamy and stories of crime. In response, McCray can only shake his head and say, “It was beautiful where I lived.”

In his memory, it was all salty-aired day trips to Pier 39 in San Francisco and lining up to eat at Nation’s Giant Hamburgers. If he squinted, he could see both the Golden Gate and Bay Bridges at night when the whole Bay Area was lit up like Las Vegas.

He remembers the vibrant Black culture and dynamic activism scene, through which he discovered that his contribution to Black empowerment would be by “reppin’ the weapon against oppression.”

His “weapon”? Clothing.

The Black culture McCray spoke of was alive in 1970s Oakland with the reverberation of the Black Panther movement, which started in Oakland during the 1960s. Growing up, he attended marches and Rastafarian festivals, where he said he found his place.

At that time, people he passed on the streets wore apparel that represented Howard College, Morehouse College, Spelman College and other historically Black schools. He saw lots of African medallions and African leather hats because of the contemporary emphasis on racial pride.

In the 1990s, he started to see T-shirts saying, “It’s a Black Thing. You wouldn’t understand.” Today, Oaklanders wear shirts that say “Occupy Wall Street,” “Can’t Breathe” and “Hands Up Don’t Shoot.”

McCray traded Oakland for Ogden in the 1990s and brought this culture of wearing his beliefs along with him. He started the Been Solid Clothing Company in 2013, where he released his own designs.

McCray received news in 2014 that sent him on a flight back to the Bay Area — this time, for a funeral. His cousin Marlin McCray was shot and killed in his apartment complex by his best friend.

Terance McCray said it was after the passing of his cousin that he found inspiration for the slogan he would begin to integrate into designs for his clothing company: “Black Love Matters.”

If it sounds familiar, that’s because it is; McCray altered the slogan of the national movement Black Lives Matter to reflect his unique perspective on Black empowerment.

McCray said he wanted to create something more focused on helping within the Black community rather than outside issues.

“This is starting to become more about us,” McCray said. “I think we’ve focused long enough on what the racists and the people who are against us think. I think we’ve got to start taking care of us.”

McCray said while it does have a tone of the Black power movement, his clothing is inclusive and for everyone, regardless of political standing.

He chose clothing as his medium for enacting change because of its ability to immediately convey his message without the wearer having to say a single word. It’s for the people who want to be part of the movement but aren’t able to take action in more dangerous ways, McCray said. He thinks a show of support as seemingly small as wearing a t-shirt is just as valid a tool for change.

“My weapon against oppression is my clothing company, my statements, my perception,” McCray said. “When you wear this shirt you are helping me use my weapon against oppression.”

A matter of taste

According to Roy Gutterman, director of the Tully Center for Free Speech, what a person wears is undoubtably an expression of their identity and a form of speech because it inherently carries a sociological message. As such, it is protected by the First Amendment.

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

The First Amendment

“The first thing you see when you see somebody is what they’re wearing, and that’s so closely linked and closely tied to how we present ourselves that it has indisputable speech elements to it,” Gutterman said.

He said to express oneself through clothing is not only a legal right but a human right. Few articles of clothing expressing political statements have the potential to rise to a level of illegality. Unless it is proven that a piece of apparel is going to “incite imminent lawless action,” it is legal to wear — but Gutterman has never seen any slogan or symbol that has done so.

“Even if it has offensive slogans on it, I don’t see anything that can be legitimately prosecutable in any public setting,” Gutterman said. “Even if you disagree with the movement.”

This precedent was set in the 1971 case Cohen v. California. The controversy began when 19-year-old Paul Robert Cohen walked through the corridors of the Los Angeles County Courthouse wearing a leather jacket that said “F— the Draft.” He was arrested, charged with “maliciously and willfully disturbing the peace by offensive conduct” and sentenced to 30 days in jail.

Cohen challenged his conviction all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which reversed the conviction in a 5–4 vote, concluding that California’s decision “could not withstand First Amendment scrutiny.”

Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan delivered the opinion of the court containing the famed phrase “One man’s vulgarity is another man’s lyric.”

“One man’s vulgarity is another man’s lyric.”

Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan

The court’s opinion said government officials cannot make distinctions in this area because “The Constitution leaves matters of taste and style so largely to the individual.”

From “F— the Draft” to Black Love Matters and from Make America Great Again to 2017’s Women’s March Pussyhats, Americans have the right to wear their beliefs without fear of prosecution.

The risk of revolt

Protest is a critical function of a democracy, said Aidan McGarry, a professor of international politics at Loughborough University. A democratic society does not work without it; they are both parts of the same narrative. The two exist in a “strange symbiotic relationship” where many of those who engage in protest against the government are doing so to retain their rights and maintain the integrity of the democracy, he said.

As fashion and clothing are vehicles for expression of beliefs — including challenges to the government — what a person wears is an effective way accomplish these objectives.

“Every time we choose what to wear and wear a particular object into the world, that can be a form of protest and revolt,” Parsons School of Design dean of fashion Ben Barry said in a live online discussion hosted by PBS.

Tanisha Ford, fashion historian and author of “Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul,” was a participant in the discussion as well. She said the collective style of a movement is determined with intention. Pieces are worn as symbols to communicate not only to the government, but to members of the community who perceive and characterize them.

“I think of it as a statement of collective politics: who we are, what we say and also who we are trying to recruit into our movement,” Ford said. “Clothing speaks without having to say anything, right? It’s one of these elements in our society that is imbued with all these different meanings, depending on who you are and how you interpret it.”

Although wearing political clothing is technically legal, Barry said the act of protest in any form is accompanied by an element of danger and risk. Dressing in ways that dramatically challenge dominant norms may be met with varying reactions from stares to harassment to violence.

Ford said when people adorn themselves a certain way as a challenge to the dominant structure, they make the choice to include their own bodies in the risk that protest entails.

“It’s actually really scary for the people who are putting their bodies on the line in order to fight for justice for us all,” Ford said.

The imagery that creates power

At the heart of a successful movement is visibility, McGarry said. A movement must capture the attention and support of not only the affected group, but those surrounding the group. For example, the success of Black Lives Matter is partly attributed to the fact that it has been bolstered by non-African Americans around the world.

According to McGarry, one of the first things a movement should want to do is attract attention to itself. Every movement has visual signifiers that become historic iconography engraved into the minds of generations. He said this can be done through a variety of outwardly expressive dimensions: song, dance, graffiti or clothes.

“The way our minds are trained, we are often attracted to the visual, the spectacle,” McGarry said. “It gets to the heart of the matter in a way that speaks to us directly.”

This is one of the reasons McCray cited as to why he chose to create clothing that immediately allows the viewer to understand his position. He noted that the first thing people do when they see others is look at what they have on; if a person is wearing something that makes a statement, it draws attention.

“Whether they agree or disagree, they can’t unsee it,” McCray said.

Barry said mainstream media tends to produce the more dramatic visual content of a protest, and this is enhanced when movements are visibly coordinated in dress. Activists have used this as a strategy historically and today to capture media attention and draw awareness to their cause.

“Coordinated fashion creates a significant visual impact,” Barry said. “That’s the imagery that creates power.”

McGarry confirms this point in his book, “The Aesthetics of Global Protest,” published in 2019 by Amsterdam University Press. The books says within the last decade, protest movements have responded to the technology of the day by using social media in combination with the aesthetics of protest. The convergence of the two promote “visual thinking” about representation and social change, effectively communicating key ideas and demands.

Ford said when thousands of women came to the 2017 Women’s March wearing pink “pussy hats” — hats knitted in the shape of cat ears — they knew that drone technology would be used that day. Wearing a brightly colored garment on the head would be captured by the drones flying over, creating an arresting visual that would lend itself to being shared by media outlets and social media.

From those visuals, the pussy hat movement received international attention and has become a symbol of political resistance and women’s rights.

If they’re wearing a uniform, McGarry said, it’s about unity — it’s about a resistance group trying to show numbers or strength. It’s a device to convince power holders that the group is significant and cannot be ignored.

Solidarity from home

Along with the visual impact, a coordinated uniform or style promotes a feeling of solidarity, community and connection amongst protesters, Barry said.

“It certainly allows someone to feel that they’re a part of something much bigger than themselves,” Barry said. “They’re part of that interdependent whole that is protesting against something in particular.”

Wearing pieces that symbolize a certain set of beliefs allows people who aren’t able to be present for physical protests to play a part by wearing or making pieces from home.

McCray said this was one of the main reasons he sells “Black Love Matters” clothing. Not everyone is inclined to travel to rallies, carry a sign or put themselves at risk by engaging in protest. Buying and wearing clothes in support still acts as an expression of what a person’s ideals are and still raises awareness to anyone who sees them.

Suffragette White

The suffragettes of the early 20th century used the color white to forge a political identity for themselves, according to a publication by CR Fashionbook magazine.

“I wore all-white today to honor the women who paved the path before me, and for all the women yet to come. From the suffragettes to Shirley Chisholm, I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for the mothers of the movement.”

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, @AOC on Twitter

The article said the leaders of the movement chose white because of its traditional use to represent femininity and purity, so it was more palatable and respectable in the eyes of the dominant power — their male counterparts. At the same time, they subverted any ideas of white representing submissive femininity by wearing it while rallying for the vote.

The 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote in America in 1920, but trailblazing women in politics continue to wear white as a nod to those who came before them. Landmark examples include Shirley Chisholm as she became the first Black woman in Congress, Hillary Clinton in her last debate during the 2016 democratic nomination for president and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as she became the youngest woman elected to Congress.

Zoot Suits

Zoot suits were worn by young Latinos and other minority men during the Chicano movement in the 1940s. According to the History Channel, the suits were flamboyant, loose-fitting, heavily padded at the shoulders and accentuated the movements of the wearer.

In 1943, U.S. servicemen hunted zoot suit wearers, beat them and burned their suits in the streets.

“Nothing about the zoot suits were explicitly Mexican, but boldy demanding to be seen was an affront to the American identity,” Angela O’Shaughnessy said in her article “Zoot suits: a fashion movement that sparked Mexican American resistance.”

Sunday Best

In the struggle for racial justice during the 1950s and ’60s, Black people challenged the power structure by wearing their best, most elegant attire while participating in marches, sit-ins and other acts of protest, wrote Ford in a journal article titled “SNCC Women, Denim, and the Politics of Dress.”

She said in the article that they used respectability as a political tool; if Black people were to be taken seriously, they would have to dress as nicely as possible. Wearing their Sunday best acted also as a direct challenge to Jim Crow-era portrayals of Blackness and made the statement that they were worthy of dignity and respect.

The Black Panther Party

The Black Power movement of the 1960s and ’70s rejected the idea that Black people should garner respect by becoming more acceptable to white people.

In a quote given for a Refinery29 article, Taniqua Russ, host of the Black Fashion History podcast said the Black Panther uniform of berets, sunglasses, afros, turtlenecks and leather outerwear “embrace African fashion as the symbol of pride and rejection of European standards of beauty.”

The image they radiated was bold and radical to the point of being empowering. Their iconically militant style told white America they were immovable.

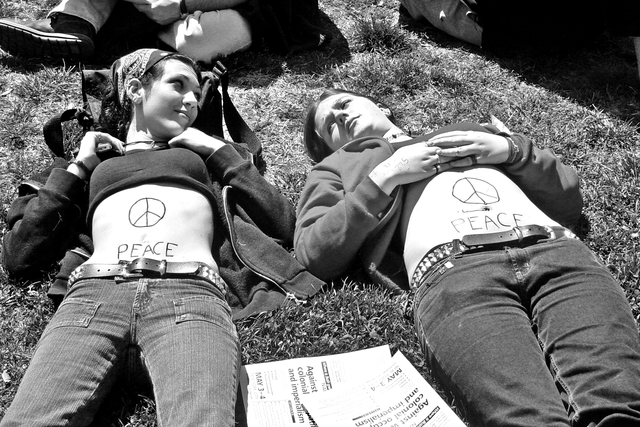

The Peace Symbol

The peace sign was adopted by anti-Vietnam war protesters in the 1960s, said Rachel Raudenbush in a research article published by the Journal of Culture and Retail Image in 2010. The symbol appeared on vans, banners, clothing, jewelry and armbands, becoming the visual icon of the anti-war movement.

The controversy of the 1969 landmark Supreme Court case, Tinker v. Des Moines, started when high school students Mary Beth Tinker and Christian Eckhardt planned to wear Black armbands with peace signs to school in protest of the war. School administration created a policy saying any student wearing an armband would be asked to remove it.

The students sued the school district for violating their First Amendment rights. The case ended up in the Supreme Court, cementing students’ right to free expression and speech.

Slogan Apparel

Michaela Angela Davis, an image activist, said in a quote for Women’s Wear Daily magazine that T-shirts, hoodies, hats and other articles of clothing with political slogans on them have become “defining apparel” of modern movements like Black Lives Matter.

“The culture is very aware of images and media, and this is a movement of social media,” Davis said. “So, if you’re in a crowd and you have any sort of message T-shirts, you’re communicating very quickly, very efficiently, what your position is.”

Donald Trump’s Make America Great Again campaign is another example of a political group that has taken advantage of a catchy slogan. Gutterman cited the iconic red hat that spurred the movement as a testament to how effective clothing is at influencing political structure.

The Pussyhat Project

Women arrived at the 2017 Women’s March in Washington D.C. donning bright pink “pussy hats.” The hats were knitted to have cat-like ears, a play on the phrase “pussy cat” and on Donald Trump’s infamous “Grab em’ by the pussy” quote from 2005.

The Pussyhat project website says the goal was to make a bold and powerful statement of solidarity and allow people who could not participate themselves to visibly demonstrate their support for women’s rights.

Slogan Masks

According to Susan Devaney in a Vogue U.K. article, while masks were designed to help stop the spread of the COVID-19 virus, people have adopted them with the same functionality as other slogan apparel. Masks have become a safety necessity in public spaces for activists protesting in the midst of the pandemic.