MaryEllen Johnson’s life looks a bit like a superhero trying to mask a secret identity. The 63-year-old is the mother of two adult daughters and lives with her husband in her native Salt Lake. Johnson is an avid gardener and an active member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Everyone seems to know her as a friendly human-rights supporter who is willing to talk about anything.

But once a week, Johnson takes on another identity as she sits down to chat with a dozen strangers about their deepest sorrows and struggles. She’s not a therapist, and she’s never studied psychology, yet she walks these people through every kind of struggle, one-on-one, from abuse to anxiety to gender identity. Every time, her goal is to help people feel a little less alone and find better ways to take care of themselves.

Johnson will never see these people in person — or if she does, she will not recognize them — nor may she even know their real identities. Yet these people trust her with fears they may never have told another soul.

Most people don’t know this side of Johnson’s life, the same way Clark Kent leads a typical life reporting for The Daily Planet when he’s not saving the world as Superman. If there is one exception to Johnson’s superhero identity, though, it is that Johnson wants everyone to know about the resources they can turn to for help.

Johnson studied education at the University of Utah and went into marketing and writing before settling down to raise her daughters. Once they were grown, Johnson decided she had to get back into the world “to start doing some good things.”

Given her diverse interests and enthusiasm for life, Johnson tends to “jump around” and “ramble into many different fields,” she said. One such endeavor she found herself pursuing was working for the Crisis Text Line.

Crisis Text Line was launched in August 2013 as the first text-based resource for struggling young adults. The company reported they were receiving texts from almost every area code in the United States just four months after their launch. There was clearly a gap to fill in resources for those in crisis.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, started in 2005 with 109 call centers. The resource began as a place to give comfort to those who were struggling with suicidal ideation and other crises, providing communication and connection at times when people need it most.

Just because crisis texting is on the rise doesn’t mean hotlines aren’t still effective: The Suicide Prevention Lifeline has served more than 2 million people since its start.

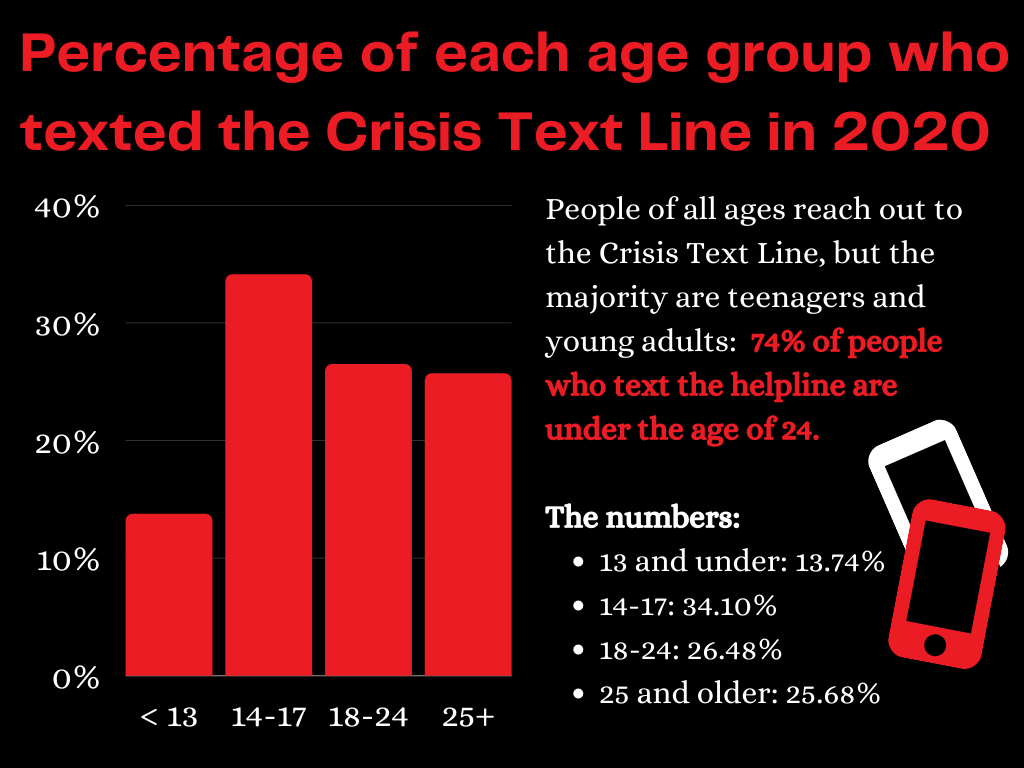

The need for a texting service, then, may be largely generational. People of all ages reach out to the Crisis Text Line, but the majority are teenagers and young adults: 74% of people who text the helpline are under the age of 24.

Enlarge

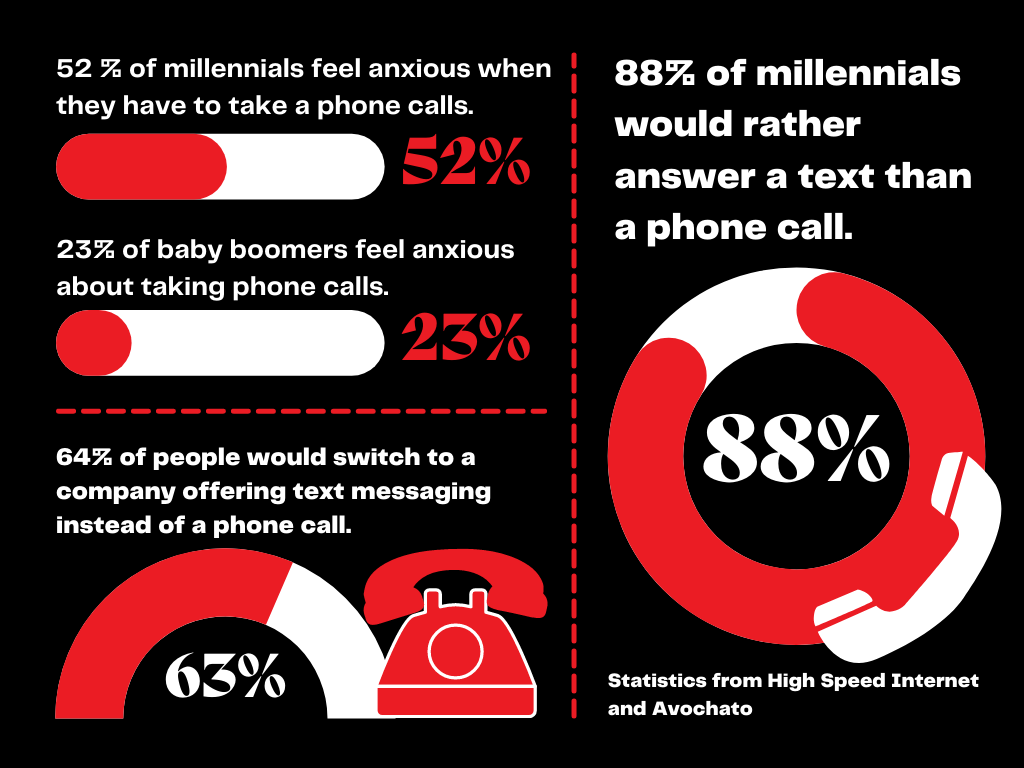

A report from High Speed Internet found that 88% of millennials choose texting over calls and 52% of them feel anxious when taking a phone call. This is in sharp contrast to the 77% of baby boomers who do not feel anxious when on the phone.

This isn’t just for people in crisis, either: Software company Avochato said 63% of survey respondents would switch to a company offering text messaging instead of calling and 75% prefer being texted to being called if their rideshare service has arrived to pick them up.

Enlarge

Crisis Text Line in particular is a place for a text-savvy, phone call-anxious generation to turn to where they can be completely vulnerable and gain hope and connection.

Still, there are benefits to calling in a crisis that might not be received when people text instead.

Calling vs. texting

Johnson is largely supportive of texting, as it is the primary way people communicate nowadays. People can get right to the point when they text without having to endure small talk. Texters also have their Crisis Text Line conversation to look back on later when they are no longer in crisis: Johnson encourages people to look back later to see how far they’ve come and how strong they are.

Matt Kleinman is a student at Brigham Young University who has volunteered at Crisis Text Line since May 2019. Unlike Johnson, Kleinman has more mixed feelings about whether it is more effective to call or text. Still, he recognizes the importance of having both resources to fill a wide range of needs.

Kleinman said calls are preferable in some instances because it’s usually easier to understand a situation quickly, convey empathy and help someone talk through a problem over the phone because there’s no waiting period the same way there is between text messages.

He also pointed out that having to “carefully craft the message” of a text with grammar and a slowed-down conversation can make it harder to be authentic.

“You can’t always say exactly what you would say if you were just talking to them,” Kleinman said.

On the other hand, he pointed out many people who experience anxiety struggle to have even a “normal” everyday phone call, let alone call a highly stigmatized hotline for help.

Texting is more anonymous and helps decrease the fear paralysis that keeps people from asking for help. Texting is also easier for teens who are in the same room as their parents or college students with no privacy because they have roommates, Kleinman said.

Statistics from Crisis Text Line show 37% of the people who reach out to the helpline have never asked for support before. Moreover, 68% of texters say they share a part of themselves with their crisis counselor they’ve never told another person.

“It’s a lot easier for many people to just send a text to a number,” Kleinman said. “If you are in a crisis moment where you’re just not safe, it might be really hard to break that barrier to make the phone call, so the text can be an easier step to getting help.”

Sexual assault victims

One such issue where stigma and fear are barriers that keep many from getting help is sexual assault. Texting is one way abuse victims gain access to life-saving help.

Lori Jenkins is the sexual assault services director at The Refuge, a resource center serving victims of rape and domestic abuse in Utah since 1985. Jenkins said The Refuge’s resources are first reached by phone, but callers then have the option to text instead if that will make them more comfortable.

This attention to communication preferences is just one part of the care The Refuge provides. Her group also sends volunteers to sit with victims at hospitals and help them get checked in to get the help and resources they need.

Jenkins called The Refuge “the pinpoint” for where people can go to get more help. Some free resources available at the center include trauma-based individual and group therapy. The Refuge also offers weekly classes on overcoming PTSD, self-blame and healing from domestic abuse and sexual assault.

All that can start with a text.

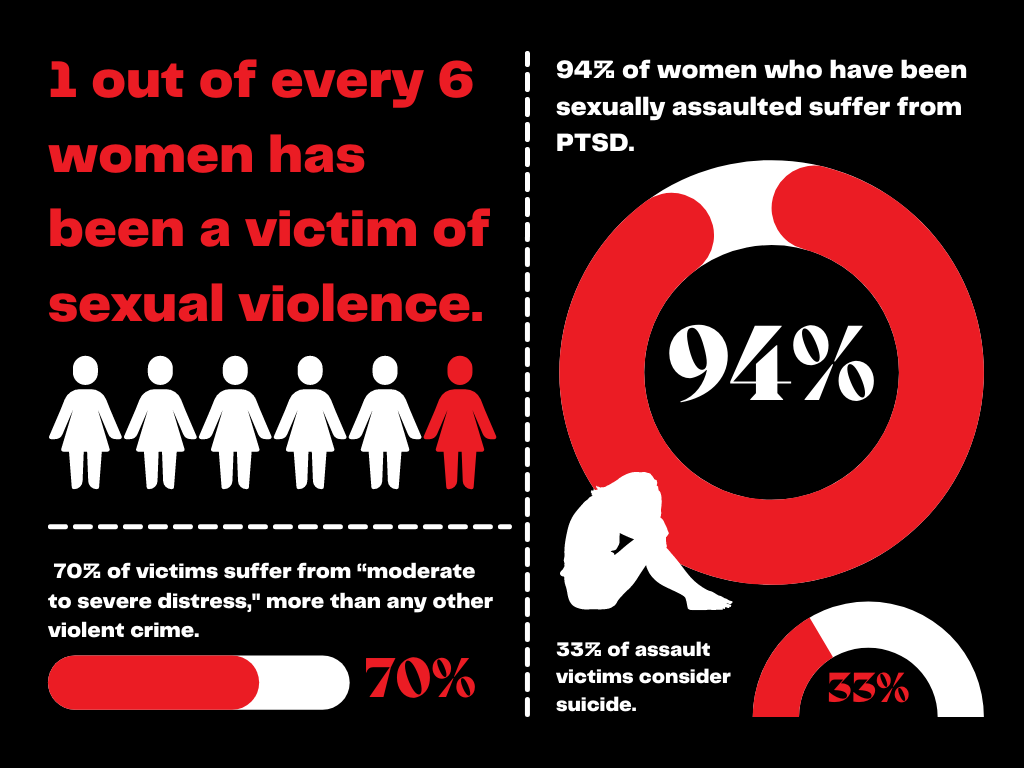

The Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network reports 1 out of every 6 women has been a victim of sexual violence.

Victims of such abuse are more likely to suffer from depressive and suicidal thoughts: 94% of raped women experience PTSD, 33% contemplate suicide and 70% suffer from “moderate to severe distress,” which is a higher amount than any other crime, the foundation said.

Enlarge

Jenkins said she wishes more people knew about the resources available to them when they are struggling with the aftermath of tragic events.

“The saddest thing next to this abuse happening in the first place is when people don’t know about these resources to get on the road to recovery and healing,” Jenkins said.

She stressed the value of fully anonymous calls and texts to give victims information and comfort.

Local resources

John Draper, who leads the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, said trends show increases in the number of people who reach out to crisis services when the hotlines receive more attention, not when rates of suicidality are higher. Awareness of resources is one of the most important parts of getting help when someone is struggling.

“More people become increasingly aware of what we do, and if they become aware, they call,” Draper told PBS in Dec. 2020. “I don’t know if it tracks directly so much with suicidality and an increase in suicidality as it does with market penetration and awareness.”

Jenkins advised people who are struggling to reach out to local centers rather than national foundations when possible. She said even though national lines can still help people find hope, they lack a lot of the personalization of local helplines that can connect people with resources near them.

“I would just encourage people to reach out and become more aware,” Jenkins said.

Utah County, for example, has free legal consultations along with all of the classes and aid at The Refuge, making it more effective for victims to reach out to those local centers instead of extending nationally. Free medical forensic exams are available for victims of abuse and assault.

Local helplines also have decreased wait times, like the 24-hour crisis line available at Wasatch Mental Health.

Johnson wants everyone to be aware of text crisis lines as a resource. “Hotlines save lives,” she emphasized. “Crisis Text Line 24/7, 741-741. So text in!”

Johnson said she’s had every kind of conversation imaginable working on the crisis line. Just when she thinks she’s seen it all, she’s asked to help someone confront a whole new kind of issue.

Some topics she’s discussed with texters include anxiety attacks, members of the LGBT community struggling with coming out to friends or family, breakups, suicidal thoughts and self-harm.

“I had to open my mind,” Johnson said. “I can talk about anything with anyone now.”

Johnson sees mental illness as “the plague of today” and said if people can’t listen to each other and talk about difficult issues, “we’re in big trouble.”

A large part of her passion for working with crisis lines is helping to reduce the stigma around seeking support when people are struggling.

COVID-19’s impact on hotlines’ evolution

Kleinman agreed the crisis line works for any kind of stress, saying he has dealt with every topic from a failed math test to suicidal ideation. He has seen it grow since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic as more people have been alone and struggling with mental health. The Disaster Distress Helpline saw an 891% increase in calls from March 2019 to March 2020.

While he still witnesses a stigma around hotlines, Kleinman sees great benefits to the privacy of using a text line.

“The goal is to help whoever’s texting in to — the phrase we say is — ‘Move from a hot moment to a cool calm,’” Matt said. “We just want to help them be able to find some relief from whatever’s intense in their life right then.”

Johnson said she has seen the Crisis Text Line evolve dramatically in the many years she has volunteered with the organization.

One newer resource is that the Crisis Text Line now automatically sends out a text offering a webpage full of resources when crisis lines are especially busy and wait times grow long.

These include hotlines for abuse, grounding techniques for anxiety, anger management guides and bullying resources. The page also shares help for grief, eating disorders, conflict resolution and even pandemic-related stress.

These stats are from the Crisis Text Line. (Made in Canva by Gabrielle Shiozawa)

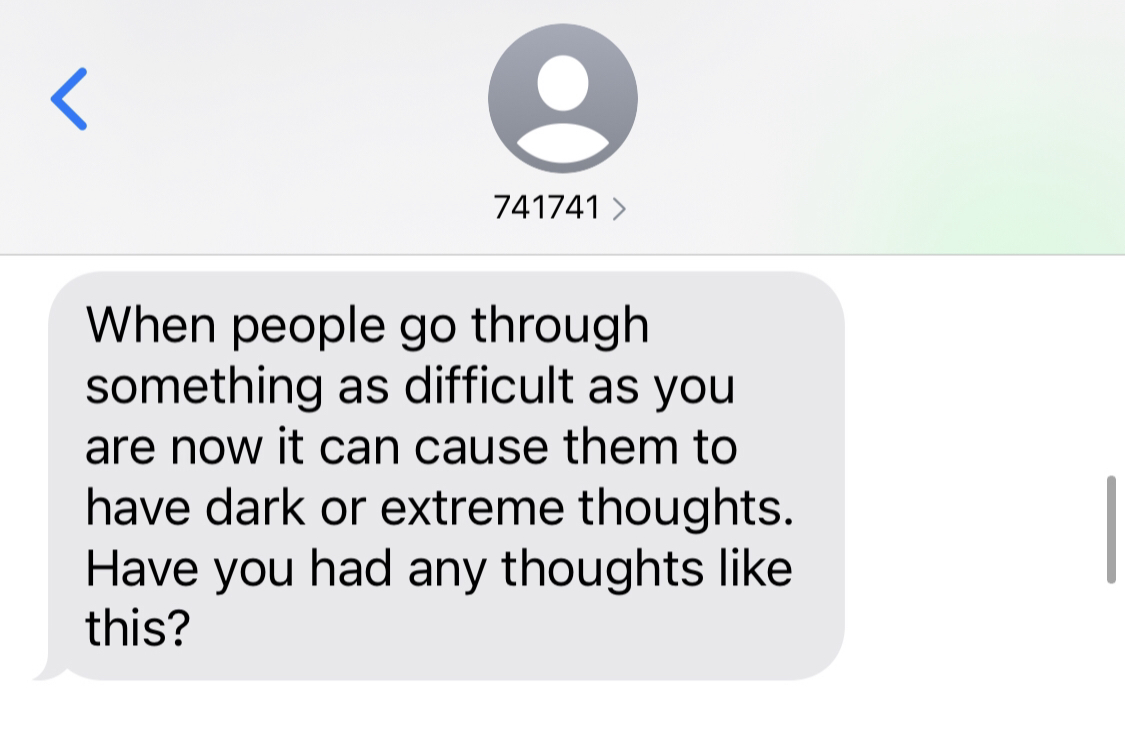

Another big difference is hotlines now ask about suicidal ideation and suicidal intention at the beginning of the conversation rather than waiting for the texter to bring it up.

Some texters will say they haven’t thought about suicide that day but they have struggled with those thoughts recently, giving the volunteers a better idea of what risk level they’re working with.

More than that, though, it gives people the feeling of relief knowing they can talk about anything with their assigned volunteer.

“Wow, that just clears the air,” Johnson said of those conversations. “It’s okay to have thoughts of suicide and to acknowledge it. I think it gives a lot of power to a lot of people to not be judged by that.”

Enlarge

Crisis lines don’t solve problems: They just help people find an equilibrium and the strength to keep moving. Sometimes all a person needs when they’re alone and struggling is to have someone who will listen to them without judgment, Johnson said.

“A lot of times that’s all they need because then they can really unburden themselves,” Johnson said. “They realize that what they’re talking about is real, and it gives power to that pain. Sometimes that’s just enough.”

Volunteers

Increasing mental health concerns means an increased need for volunteers to staff these services. An August 2020 survey conducted by The Harris Poll in connection with suicide prevention groups found 93% of people said they feel suicide is preventable at least sometimes, and 78% of those same people said they would be interested in learning how to play a role in helping someone who may be suicidal.

Still, many people are hesitant to sign up based on a lack of spare time or a lack of psychological background. The same Harris survey showed a strong stigma remaining around the discussion of mental health topics, as people tend to believe they will say the “wrong” thing to someone who was struggling. Of this group, 30% of people said they fear they would make those in crisis feel worse, 24% worried talking about it would increase the likelihood of taking action, and 22% thought they would not know what to say or do.

However, people who do volunteer, like Johnson and Kleinman, see benefits they never could have imagined.

“Sometimes — this might sound odd — after my shift, I feel really great,” Johnson said. “You can tell when you’ve reached out and you’ve really connected with a person.”

Volunteer numbers increased dramatically at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic as more people were stuck at home and seeking ways to serve. More than 15,000 people applied to be counselors at the Crisis Text Line from March to April 2020.

Jenkins defined the three different kinds of people she sees volunteering at The Refuge and elsewhere.

First, there are general community “do-gooders” like Johnson.

There are also people who experienced abuse or had a loved one who did: Jenkins said these people either want to “pay it forward” to help others or had poor experiences and want to try to make someone else’s recovery go better.

The third group includes college students looking for internships or volunteer hours.

The latter group describes Kleinman, who originally got involved with Crisis Text Line to fulfill volunteer hours for his applications to medical school. He started out volunteering at the Provo Marathon and related events but decided he wanted to pursue something with “more substance to it.”

Recently Kleinman’s career path changed to nonprofit work, but his experiences with the text line created a passion he said will follow him for life.

“I have just loved crisis counseling,” Kleinman said. “My plan is basically to do it forever because I just really love it.”

Still, some crisis counseling shifts can take a heavy toll. The Text Crisis Line assigns each volunteer a supervisor who monitors conversations and checks in with them to see how they’re holding up. Johnson said volunteers can also choose to skip conversations and send them to a different volunteer if the content is triggering.

“Say I have a really tough conversation and I’m not near my shift’s end time, I can just say, ‘Hey, I gotta go, this is tough,’ and I’ll just go and do something to decompress,” Johnson said. At times like these, she usually works in her garden or goes for a walk. “It’s important to take care of yourself after shifts. Some shifts aren’t that stressful, but it’s important to pay attention to that.”

So Clark Kent puts his glasses back on and goes back to normalcy, and Johnson and other crisis volunteers go about their everyday lives. But hiding just beneath the surface is an urgency that compels them to help others and let them know just how many resources there are to help them keep moving forward.

“You’re never really alone,” Johnson said. “You know, we all just need to do our part. I think that’s a lot of it because you never know when you’re going to be on the opposite end. You just never know.”

Enlarge