Alice Paul is pictured in the 1920s. Paul wrote the proposal for the Equal Rights Amendment. (Photo courtesy of nps.gov)

In 1923, Alice Paul, a woman who had given her all to the suffragist movement and who was well-versed in the cause of promoting women’s rights, wrote a proposed amendment to the Constitution.

This amendment would allow her dream of full equality for women, “ordinary equality,” as she called it, to come to fruition.

This amendment was called the Equal Rights Amendment, and it was designed to provide a way for women’s equality to be finalized in the governing document of the United States.

Although it was drafted and brought to Congress under Senator Charles Curtis in 1923, the Equal Rights Amendment is still not ratified in the U.S. Constitution and is not in effect. Both the national and statewide fight for the ERA has been a long one, resulting in a series of victories and losses for all groups involved.

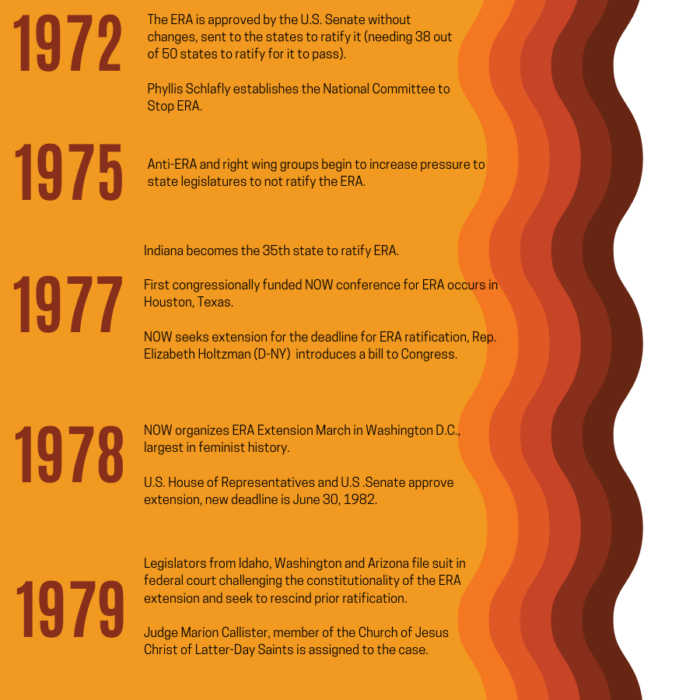

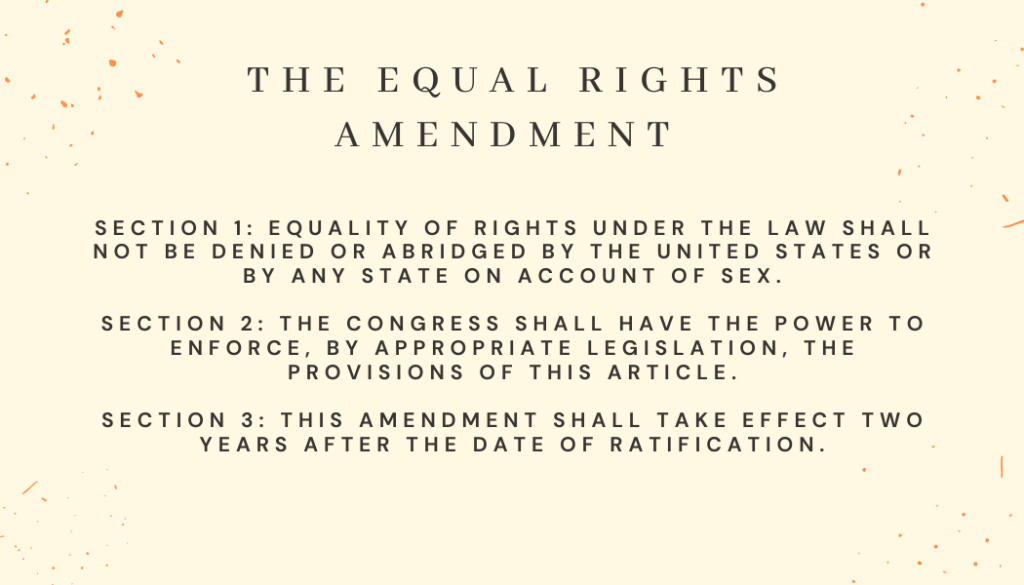

The Equal Rights Amendment contains three sections. The ERA was proposed in 1923 but still has not been added to the Constitution. (Made in Canva by Emma Keddington)

Today’s politicians and advocacy groups are still majorly involved in the battle of ratification, with the most recent update occurring when Sens. Mitt Romney (R-UT), Ron Johnson (R-WI) and Rob Portman (R-OH) wrote a letter to the national archivist, asking for his commitment to not certify the amendment into the Constitution.

Despite the pushback against the ERA, the fight still continues on, held together by people of all backgrounds fighting for women’s equality to gain a place in the Constitution.

Misinformation and the ERA

“I can’t believe we’re still having this argument, still trying to justify the need for women, human beings, to have equal rights,” BYU alumna, writer and activist Heather Sundahl said.

Sundahl’s earliest memories of the ERA come from when she was a little girl in the 1970s, surrounded by the intense anti-feminist rhetoric that defined that time period.

"Why wouldn't we want equal rights?" Heather Sundahl

“I can remember saying to my mom, why wouldn’t we want equal rights?” Sundahl said.

She was met with an answer commonly used to justify the opposition to the ERA: if this passes, that means women will have to go to war. It means there won’t be private bathrooms, abortion will be rampant and gay marriage will be legalized.

“Okay, well, we’ve already got gay marriage, unisex bathrooms. Women are in combat. Abortion rates have gone down. Now what’s our excuse for not passing the ERA?” Sundahl said, referring to what has transpired since she was given that answer in the ’70s.

Information and rhetoric such as this is still extremely common in the conversation surrounding the ERA.

When the National Organization for Women (NOW) took up the ERA as a renewed cause in the late 1960s, the group was met with intense opposition from right wing groups such as the Eagle Forum, Phyllis Schlafly’s STOP ERA and many large, conservative institutions, including The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Rhetoric was tirelessly reiterated that the Equal Rights Amendment would tear away at the fabric of society, ruin the family unit, destroy gender roles and strip women of their claimed “privileges.”

These efforts gained so much traction that NOW’s efforts to ratify the ERA were pushed down and the power that NOW once held in Congress was diminished.

While the ERA battle is not covered in the media as much anymore, the intense rhetoric of the ’70s and ’80s still holds its place in the conversation surrounding the ERA, according to Joanna Smith, a Utah-based ERA activist with strong historical ties to the movement.

“I’ve sat in on meetings with legislators who had no idea really what it was about or were packed full of misinformation from 50 years ago,” she said.

Smith recalled the efforts to spread information that she said was not even slightly aligned with what the ERA actually contained.

“First of all, the ERA is only 27 words. It’s really short, pretty clear and self-explanatory — there is nothing opaque about it,” she said.

Smith said pamphlets created by anti-ERA organizations and institutions said if the ERA was passed, women would be subject to all types of problems, including being called into the military and deployed.

An example of an Anti-ERA pamphlet shows the fears of opposing groups. People who opposed the ERA were afraid the amendment would force women to serve in the military if it was passed, among other concerns. (Photo courtesy of the National Archives)

“Keep in mind, this was a generation who was very aware of World War II and Vietnam,” Smith said.

These pamphlets would also state how if the ERA passed, “people would be allowed to change genders anytime they wanted and there would be no difference between men and women,” Smith said. “Another one was that they would penalize you for being a stay-at-home mom.”

These were valid fears, Smith acknowledged, especially for the time. However, they were not based in fact, she said.

The reality of the ERA

According to a research article by Jennifer Weiss-Wolf from the Brennan Center for Change, if the ERA is passed it will simply “enforce gender equity through legislation and, more generally, (create) a social framework that acknowledges systemic biases.”

Smith said that because the U.S. still doesn’t have the basic enforcement of gender equality in its Constitution, supplemental bills have been put in place allowing women to be protected under the law. Bills such as the Violence Against Women Act and the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act would not be needed if sex discrimination was directly addressed in the Constitution.

“Historically, the arguments in the 1970s and ’80s (against the ERA) have come true already,” said Altana West, operating director at the Alice Paul Institute, an organization dedicated to the life and works of the founding ERA creator. “It’s not a light switch, like as soon as the ERA is in the Constitution it’s going to change everything.”

West said in reality once the ERA is passed it will merely allow people who feel discriminated against based on sex — or any gender minority — to have a better standing in court.

Among these solidified impacts the ERA could make in the courts, there are also other more symbolic impacts the ERA could promote, according to Kelly Whited Jones, head of the Utah chapter of the ERA Coalition.

“More so than even the tangible impacts in the courts, (the ERA) will provide symbolic and intangible heightening of respect for women,” she said.

Not only would the passage of the ERA address the issues of sex discrimination, it would be a symbolic declaration “enshrined in the most profound document” of our country, Whited Jones said.

“(The ERA) has a life to it, a longevity to it,” Whited Jones said. With the amendment’s passage, she said the “level of respect in general would rise for women and inspire even more laws that will support women in safety issues, sexual assault and domestic violence.”

The weight of constitutional protection would provide a country where women can feel safe and respected, she said.

“We are so close, we can taste it,” Whited Jones said, noting the progress made with the ERA. “We really are on a trajectory in history where we are moving toward (its passage).”

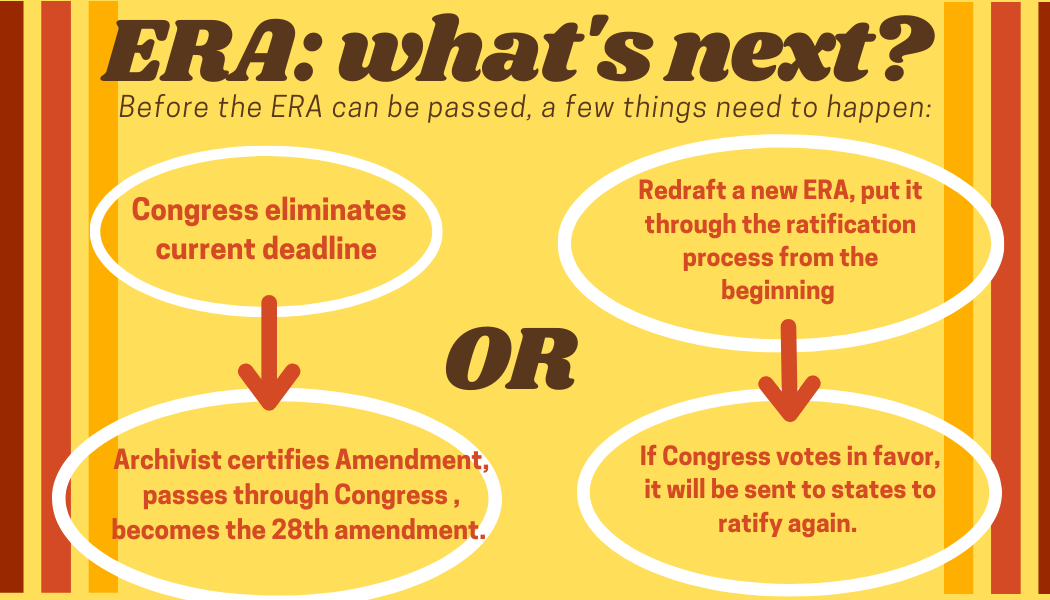

Most recently, Virginia became the 38th state to ratify the ERA on Jan. 27, 2020. The 2-year waiting period stipulated in the proposed amendment passed in January 2022, making the next focus removing the time limit previously put on the ERA by Congress. This is an issue major leaders in the ERA movement are working to change.

There are a few options for how this can work, according to West. One is to have the time limit completely removed, something many ERA activists argue is constitutionally probable especially considering the precedents of previous amendments.

A graphic explains the next steps in the ERA ratification process. Before the ERA can be passed, the deadline in place must be eliminated or a new ERA must be drafted. (Made in Canva by Emma Keddington)

West gave the example of the 27th Amendment, which was originally proposed in 1789 and ratified in 1992, an amendment that evidently had no time limit.

The other option would be to start over by re-proposing the ERA to Congress and sending it back to the states to get it ratified. This was an option supported by the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, an early proponent of the ERA.

The ERA and Utah

Just as important as the national conversation around the ERA is the part Utah has played both in the fight for and against the Equal Rights Amendment.

According to Whited Jones, there is an equality clause in the political section of Utah’s constitution that uses very similar language to the ERA and has been in place since 1896.

Despite this basis of equality, Utah and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints played a large part in the push against the ERA in the 1970s.

The attacking rhetoric of the ERA evoked the Church to publicly come out against the ERA along with sponsoring efforts to lobby against it.

According to Smith, whose mother-in-law, Elva Barnes, was heavily involved in the ERA fight during this time, the Church would call people to go out in pairs to persuade people to vote against it. Members of the Church who were part of the pro-ERA movement were often released from callings or censured by Church leaders.

The culmination of the Church’s fight against the ERA came in 1977, when a NOW-organized ERA convention took place in Salt Lake City. The Church called people to be present to vote against it, thereby fueling the fire against the amendment in Utah.

Smith recalled the experience of her mother-in-law, who felt her months of work were “shattered” by the Church’s anti-ERA actions.

While the Church still has not come out in support of the ERA, the rhetoric surrounding it has lessened in intensity since the ’70s, allowing more dialogue to be shared across parties and ideologies in its congregations.

Most recently, a 2021 bipartisan bill was proposed by Sen. Kathleen Riebe (D-Salt Lake City) and Reps. Karen Kwan (D-Murray) and Kirk Cullimore (R-Sandy) resolving to ratify the ERA in Utah.

Whited Jones, who has worked closely with legislators to promote similar bills, emphasized the direction Utah is going with the ERA is positive.

There are also groups and individuals within the Church who believe strongly in the ERA, such as the Mormons for ERA.

Anissa Rasheta, a leading figure in this group, is working to dispel myths about the ERA that are common in Church communities.

“I speak a lot with Church leaders and state representatives that are members of the Church and try to figure out ways to communicate without it feeling like a battle,” Rasheta said. “I’ve been able to have great conversations.”

The reality of this amendment is that there will always be debate, but the leaders of the movement are hopeful for its eventual passage.

Smith said despite the “long, arduous process” of ERA ratification, she still holds onto hope.

“I believe I’ll see the day for the ERA to be passed in Utah and nationwide,” she said.

Rasheta similarly discussed how proud she is to “carry the torch” for many women who have come before her as she helps carry the ERA toward the finish line of ratification.

Hope for the future

Much of this hope for the future will come from a young generation of women taking up the cause advocated for by so many women before them for almost a century.

“The next generation is just amazing,” Sundahl said. “I’ve studied feminism and diversity for 30 years, and (the younger generation) is still teaching me and helping me see things in different ways.”

A young girl holds an “ERA YES” sign in front of the Utah State Capitol. (Photo illustration by Emma Keddington)

The ERA campaign does not just belong to older generations of women, but it is something advocates emphasize younger women should become invested in and educated on.

“If young people are passionate about the ERA they should learn about the history, and they should educate everyone around them without any lines of ambiguity,” Smith said. “Young people who are interested: Reach out to people that have done it before, that are advocating, because they’re tired. They’re paying an emotional price, but they have so much knowledge.”

"Young people who are interested: Reach out to people that have done it before, that are advocating, because they're tired. They're paying an emotional price, but they have so much knowledge." Joanna Smith

Chloe Vickers, a BYU student studying nursing, remembers when she first learned about the amendment in her Global Women’s Studies class. She said she was thrilled to learn about ERA history.

“I find the history of it fascinating, including the differing perspectives of having women think that it’s going to take away their rights and then having women that think it’s going to empower them,” she said.

She said when she first heard about it, she didn’t realize it was not yet ratified, coming to that conclusion only after researching it specifically.

She also learned about it through entertainment such as the recently created television show “Mrs. America,” which details the experiences of women involved in the ERA conversation in the 1970s and ’80s.

“It hasn’t really been talked about — our generation doesn’t know a lot about it because it hasn’t been in the media as much,” she said.

Vickers agrees it is important to talk to younger generations of women about what the ERA actually entails.

Sundahl emphasized how important it is to remember the ERA will not take away the rights of men but rather add to the rights of women, pushing society to embrace critical thinking.

“It’s important to take things and look at them by pulling back from your emotional response — just take a pause and really look at things,” she said.

Overall, advocates say there is hope for the future as the ERA continues to be discussed and advocated for. Those active in the fight for its ratification are confident their work will pay off and that gender equality will soon be permanently situated in the U.S. Constitution.

“Your voice is the future. What we’re working for and building is an equal future for all of us,” Whited Jones said. “Women were left out on purpose. We can correct that. We can’t rest until we right that wrong.”