April 27, 2017

Sixty-seven-year-old Richard Macdonald had a taxing sleeping pattern, waking up every one or two hours throughout the night. He’s no insomniac – his condition is much more common and affects approximately 200,000 Americans. He’s the parent of a diabetic child.

“I used to get up in the middle of the night every couple of hours and do a blood test with her asleep,” Macdonald said, who would finger-prick his 8-year-old daughter in order to measure her glucose levels. “I got down to where I could do it without waking her up.”

Nights are the scariest moments for Macdonald – if his daughter’s glucose levels fall too low, she could fall into a coma and die in her sleep. However, because the company that manufactures her glucose-monitoring sensor also released an app that allows Macdonald to track his daughter’s glucose levels constantly, he no longer needs to travel to her room every two hours.

“I have my clock and I have my iPhone plugged into the top of the clock — it’s on all night — I just open one eye, look at it where I can see the time and her blood sugar number,” Macdonald said. “No more getting out of bed, no more traipsing into her room.”

''High blood sugar doesn’t have an immediate effect, but it has a long-term effect. Heart disease, going blind, neuropathy in the feet and needing to have feet amputated, all of those things can happen.'' Richard Macdonald

Yes, there’s an app for that.

Macdonald’s app, produced by Dexcom, is one of many healthcare-oriented mobile apps in a recent trend towards making medical information available on phones. Mobile medical apps allow for medical information and services to transcend the doctor’s office, thereby giving users a constant reference for tracking and improving personal health. As apps have begun to flood the medical market, health experts and government agencies struggle to regulate these products to ensure that apps do not compromise patients’ health.

Dexcom’s app technology was first cleared for approval by the FDA in January 2015. The entire system consists of a sensor that penetrates just under the skin and continuously monitors glucose levels in the tissue, which then transmits to a monitoring device worn on the person. That device additionally connects to the person’s phone, who can then designate as many as five other people that can track the glucose levels in real-time through Dexcom’s app developed for the iPhone.

Dexcom’s Share technology is a unique blend of mobile apps paired with devices that allow people to track glucose levels constantly, erasing parents’ fears of the unknown during a child’s play time in between the finger pricks and blood tests. Other apps are usually stand-alone products that don’t rely on additional devices or hardware, and quite often they are free.

From Dexcom, Inc.

Such apps range from ideas like personalized information of a user’s menstruation cycle, to therapeutic exercises for lazy eye, to immediate connection with a doctor via text.

Although these apps have only existed for the past few years – in tandem with the advent of smart phones – similar program-based medical references have existed for computers, palm pilots and some mobile browsers for over a decade.

Epocrates produced its first mobile “app” for PDAs in 1999, and has been a staple drug reference for physicians ever since, allowing doctors to determine proper doses and side-effects for any drug. Such medical reference apps have become a necessity for medical students as well.

Denver Brown, 30, a student in BYU’s nurse practitioner program, uses Epocrates as well as several other apps to refer to proper medical treatment for patients while in clinical settings.

“It’s 100 percent necessary to provide thorough, long-term assessment when I’m not familiar with something,” Brown said. “I use these apps in a clinical setting every day, and I’ll never stop using them.”

History of medicine and phone apps

Balancing medical app benefits with safety

Healthcare apps have become more patient- and user-friendly with the popularity of smart phones, allowing people to find medical information and self-administer proper healthcare without having to consult a doctor. This recent change in doctor-patient communication raises issues as to the safety of apps that could potentially deter patients from seeking healthcare from their physicians.

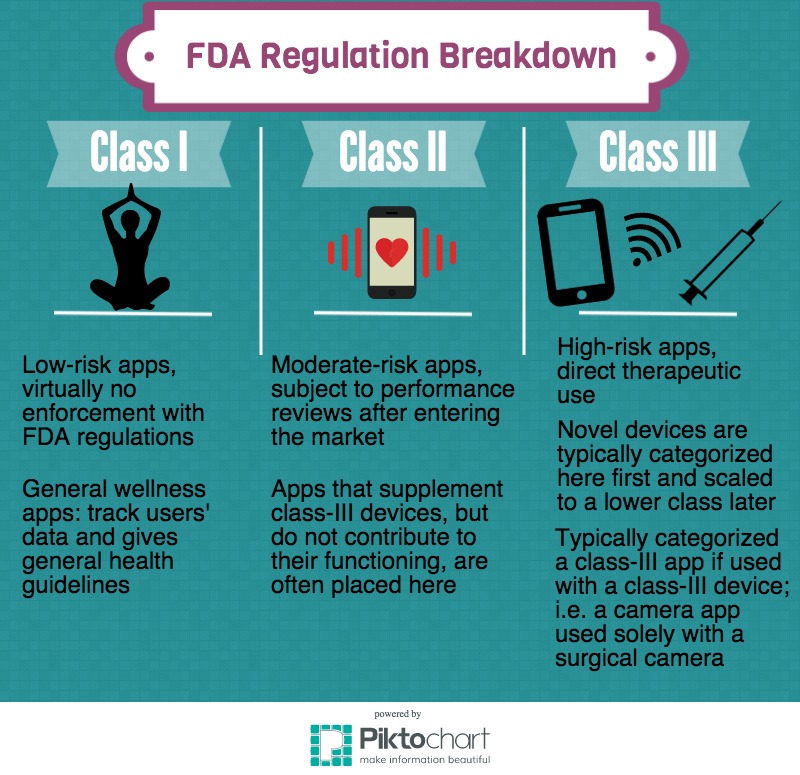

The FDA issued new rules in January that define three classes of mobile medical apps and devices and the regulations imposed upon those apps. High- and intermediate-risk apps require approval by the FDA before entering the market, and some surveillance thereafter. Although some regulations exist for low-risk apps, the FDA announced it would not seek to enforce compliance with those regulations for each mobile medical app.

Digital Health Associate Director Bakul Patel from FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health said that the new guidance on these regulations helped eliminate double-oversight with other regulatory bodies and encourage innovative health technologies.“We want to promote patient engagement, at the same time protect patient safety,” Patel said in a webinar. “We are very cognizant of the fact that technologies will evolve, will become smaller, better, cheaper.”

Some apps directly intend for patients to receive their healthcare for cheap. San Francisco-based app First Opinion was premised on the notion that the majority of visits to a doctor’s office are unnecessary and costly. Its goal is to help its users understand when such visits are necessary or not.

What else do these apps offer?

Utah native and BYU graduate McKay Thomas started First Opinion in 2014 shortly after he and his wife had their second child. Currently only available on iPhones, First Opinion allows users to text a network of doctors 24/7 on health concerns, even take and send pictures of things like rashes or skin lesions. A doctor responds on average within 5 minutes and, after some follow-up questions, gives the person advice as to what may cause the problem.

''We are very cognizant of the fact that technologies will evolve, will become smaller, better, cheaper.'' Bakul Patel

“First Opinion is really targeted to be the first place you turn when you have a question, that isn’t necessarily serious enough for you to rush off to urgent care, or schedule a doctor visit that’s going to cost a copay and at least half a day off of work,” Thomas said.

First Opinion is restricted to its namesake – only giving a doctor’s first opinion rather than an official diagnosis or a prescription. Such actions would require the company to comply with more FDA regulations to ensure that patients receive appropriate healthcare.

In order to ensure that First Opinion users get the right healthcare needs, the company has a selective hiring process for its doctors – only 1% of applicants receive employment.

Additionally, the majority of doctors in First Opinion’s network are of Indian heritage. When asked about the reason for this, Thomas said in an email that the company “decided to explore a more global view that would allow us to address the actual needs we were seeing from our users and at the same time make it more affordable, and in most cases free.”

Despite the wide array of medical apps available in the US and other major markets, not all healthcare services can fit in one’s pocket. German healthcare company Caterna admits that its software program treating children with amblyopia – also known as lazy eye – would be inefficient as a phone or phablet app.

Caterna uses simple games and a series of patterns on the screen to train and therapeutically improve a child’s weak eye.

“Because the child has to move and focus the eye, it really only works on a computer with a large enough screen,” said Markus Müschenich, a mentor and investor in the company. Instead of creating a therapeutic app, Caterna created an app that allows parents and doctors to monitor a child’s progress.

Medical apps face problems in different markets

German healthcare companies manufacture products and apps at an increasing rate. Other German-based healthcare apps include Clue, a mobile journal for tracking menstruation cycles, and Klara, an app similar to First Opinion in that it allows users to send pictures of irritated areas of skin to a doctor for a professional opinion.

However, most apps that have price tags or other devices attached have difficulty becoming available in multiple markets. Caterna, for example, is prescribed by doctors in Germany and allows for patients to be reimbursed through health insurance. In other countries, patients have incompatible insurance and are forced to pay out-of-pocket for the program.

Likewise, Dexcom users in the U.S. typically pay only 20 percent for the glucose monitoring kit and the insurance company pays the rest. Although Dexcom is available in 35 other countries, non-U.S. patients also have to pay for the $800 device on their own.

''This is testing the limits of what’s possible — it’s the bleeding edge, and it’s our job to be a good player. There are so many more things that we can do.'' McKay Thomas

“It is a slow and long process of doing trials in those countries in order to get reimbursements inside those countries,” said Jorge Valdez, chief technical officer of Dexcom. “So that really limits our sales, even though the regulatory system outside the US is simpler than it is here in the US.”

Despite the difficulties achieving global availability, medical app developers are optimistic about the future of mobile medicine.

“This is testing the limits of what’s possible — it’s the bleeding edge,” said Thomas. “And it’s our job to be a good player. There are so many more things that we can do.”