April 27, 2017

Choking back tears, Mari Tsosie picked up a box, placed it on her hip, took the handle of her suitcase and stared at her now empty BYU dorm room. It was the winter of 1991 and Tsosie had just finished packing her entire life into a suitcase and several small boxes. For almost as long as she could remember, Tsosie pictured her time at a university with hope and opportunity, only this moment ended much earlier and different than she first planned.

Being the first in her family to attend college, she was now the first to drop out.

It was very difficult on my self-esteem to just keep fighting because what they considered to be their ‘base level’ was all new to me in every aspect. Mari Tsosie

“I quit school because I just felt that I couldn’t do it and [believed] the false idea that I wasn’t intelligent,” Tsosie said. “It was very difficult on my self-esteem to just keep fighting because what they considered to be their ‘base level’ was all new to me in every aspect.”

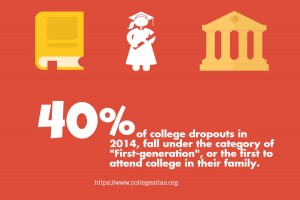

College statistics show students with no other family experience in higher education take a longer time to graduate. (Created by Jessica Banuelos)

A 2011 study from the Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA indicated only 27 percent of first-generation students earn a degree after four years and only 50 percent of them after 6 years, compared to continuing-generation students who graduate at a rate of 42 percent in four years and 64 percent in six years.

No one pursues higher education with the intention of dropping out. For students like Tsosie, first-generation minority college students have an increased chance of dropping out due to challenges such as financial struggles, intellectual difficulties and lack of social support.

Those who overcome these obstacles and find success through increased financial resources and familial support are able to graduate their college or university and open doors that would have otherwise remained closed to them.

##################

As a young girl growing up in southern Texas, Tsosie experienced extreme poverty while living under the roof of an abusive father and a mother who could not read or write in English. Growing up on frequent food stamps, second-hand clothes from the local dump and live-in mice and roaches, Tsosie observed the difference between the treatment of her family and other families within her community.

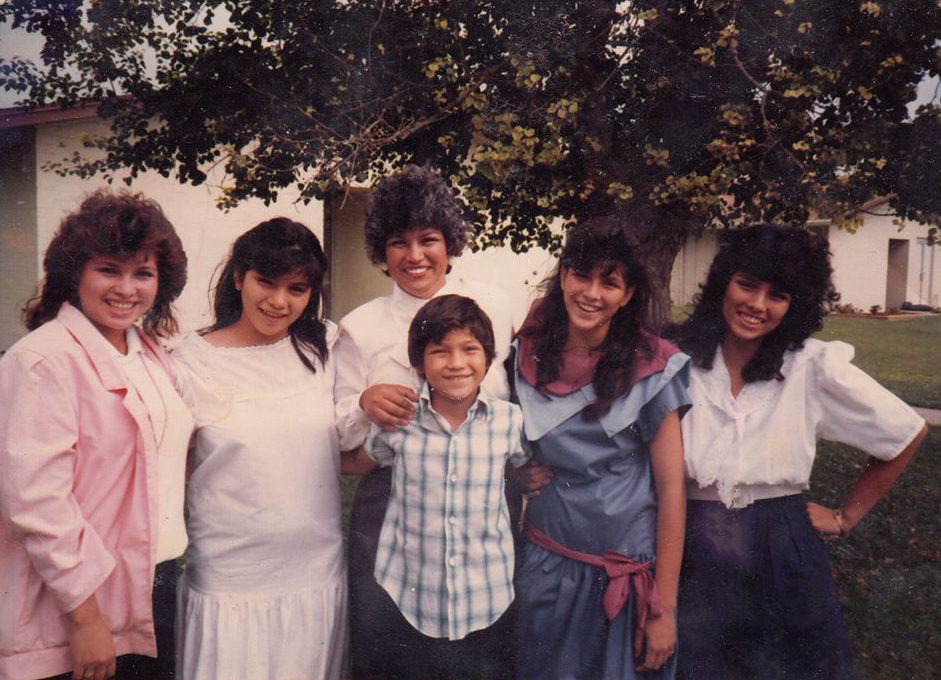

As a young girl, Mari Tsosie (far right) realized that education would be her way out of extreme poverty. Tsosie grew up in southern Texas. (Photo courtesy of the Tsosie family)

“I didn’t like it,” Tsosie said. “I saw the ones that were treated acceptably [and they] had education. I came to an understanding of, ‘Well, I just can’t gain knowledge, I have to be at the top so I can understand.’”

It was at that moment, Tsosie vowed to use her educational pursuits as a way to escape, break the generational cycle of poverty and liberate herself from a life she did not want to live.

Most first-generation minority students who are the first in their family to attend college are often not encouraged by family to pursue higher learning. That is their cross to bear as the first in a line of successors to change the family norm and way of living.

Unlike some of their family members, these daring students see education as a way for a better life. They are the pioneers of their families. They are the possibility of a new future.

###################

Although Tsosie managed to graduate high school at the top of her class, she quickly learned she wasn’t as prepared as she thought upon arriving to Brigham Young University in 1989. Although scholarships helped her get to the school, the rigors and demands were unanticipated and Tsosie lost every single scholarship she earned.

“I was always playing catch up,” Tsosie said. “I was always behind. Even though I had come out with A’s, the level of preparation these students had at BYU was much higher…. I struggled from the very beginning academically.”

To continue her education, Tsosie got a job that managed to only cover her rent. Her one-dollar daily food budget allowed her to choose between a 75 cent pack of ramen or a dollar burrito.

“I didn’t have parental support,” Tsosie said. “My family had never been to college. They didn’t understand the difficulties involved. They didn’t understand that scholarships actually run out and that college is not free.”

Many first-generation college students find themselves in similar situations and have no source of financial income other than part-time jobs. According to a study by the American Association of University Professors, working 10-15 hours per week on campus are optimal for a student’s academic success and retention. Students who do not work, work more than 15 hours or work off-campus are not as successful academically and have a lower retention rate.

The Multicultural Student Service Office at BYU assigns advisors to students who are the first in their family to attend college and come from low-income households like Gabriela Teniza.

20 year-old Gaby Teniza is a junior from Colton, California. She is the oldest in her family with Mexican immigrant parents. She wanted to attend college and inspire her younger siblings to do the same. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Banuelos)

Having to personally pay for her expenses, Teniza has struggled during her time at BYU as she juggles school responsibilities and also affording ongoing treatment for a brain tumor.

“My parents did what they could. They don’t get paid that much. They were always confident that it was going to be ok, but there wasn’t any money to prove that. I think the only thing that got me here was that I got a Multicultural Student scholarship.”

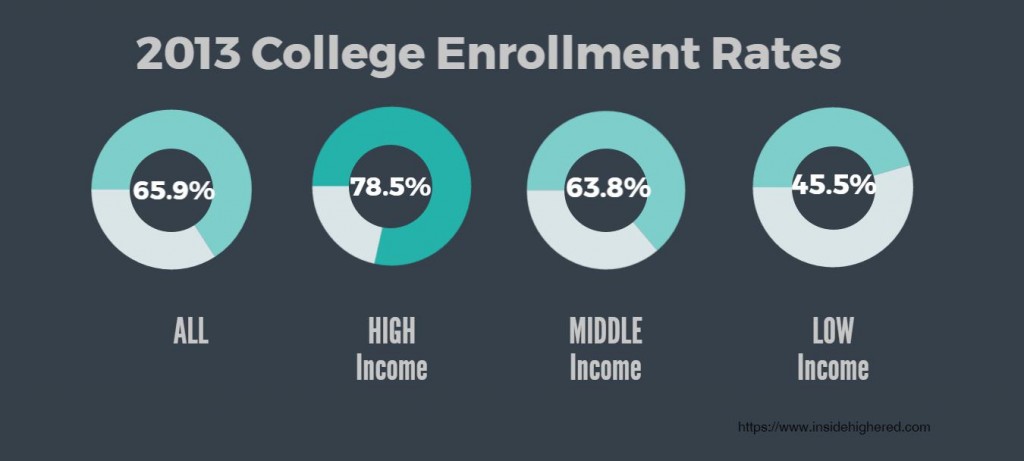

Researchers Mandy Martin Lohfink and Michael B. Paulsen discovered that first-generation college students with higher incomes were more likely to persist and push through their academic endeavors than their same peers of a lower-income. Written in their 2005 article found in the Journal of College Student Development, Lohfink and Paulsen inferred that lower-income first-generation students were disadvantaged by their parent’s lack of experience and also economic characteristics.

Since 2008, the lower class showed the highest decrease in enrollments in year 2013. (Created by Jessica Banuelos)

According to College Board, the national average cost for a public four-year in-state college cost was $9,417 in the 2015-16 school year. For private nonprofit four-year schools, the average tuition was $32,334. Out of the 22.8 million students who attended school that year, only 33 percent of them received pell grants. The maximum pell grant given was $5,775 and the average amount given was $3,724. This leaves a majority of the tuition cost unmet for students in need, especially the first-generation minority students.

The problem for first-generation minority students is that culturally any debt, even in the necessary pursuit of furthering education, is seen as a road block that completely stops the students from progressing. They would rather receive grants, scholarships or work during their college years than get into debt. Continuing-generation students are not as negatively impacted with debt and grant aid is unrelated in the choice to continue their education pursuits.

While all students may try to get in as little debt as possible, the first-generation minority students aversion to loans can be attributed to their culture, upbringing and need for self-sufficiency.

Lohfink and Paulsen continued, “The findings of this study provide another reason for caution in the movement from need-based to merit-based state grant funding, and encouragement for continued and expanded funding of federal Pell grants.”

##################

Astrid Melendez, 19, from Houston, Texas is a sophomore and the third among her siblings to attend BYU. Her inspiration to attend college are her parents who are from El Salvador and Mexico and never had the chance to attend school past middle school. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Banuelos)

Within months of her decision to drop out of BYU, Tsosie called her mother in tears while expressing her worries. She didn’t know what to do and felt lost. Her mother responded the best way she knew how: “Just have faith and pray. Everything will work out.”

While grateful for the advice, Tsosie had seen roommates and colleagues receive food, money and other support whenever they needed to feel successful.

“That’s the most my parents could give me and that’s ok,” Tsosie said. “But that demonstrated the imbalance, the difficulty for students that don’t have parents who understand what is required to succeed in college.”

Often, first-generation college students lack mentoring and knowing where to ask for help. Sharon Tapahe, an advisor for Native American students at BYU, schedules monthly appointments with the students to guide them through their college experience.

Tapahe, a first-generation college graduate herself, said. “I try to teach them skills or refer them to campus resources that will help them. I also will share some of my personal experiences of my time in college.”

Not only can first-generation minority college students struggle intellectually in the classroom, but also they can feel alone in the process. While their immediate family may not be able to relate to the new environment and demands, these students reach out to their peers, professors, advisors and trusted leaders.

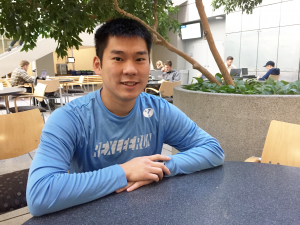

Kevin Ung, a business major at BYU from Virginia, was raised by his grandmother while his Chinese refugee parents worked out-of-state. His struggle to adapt to the college atmosphere was overcome by the support found through mentors and friends.

Kevin Ung, 23, from Falls Church, Virginia is a junior studying business and the son of Chinese refugees . Ung said his goal is to work for non profit organizations and give back to the community. (Photo courtesy of Megan Bahr)

“There were times throughout my first semester that I just got homesick or I felt that I couldn’t do things because I didn’t have anybody to guide me. I had to depend on friends or other sources like church leaders,” Ung said.

Over the past several decades, colleges and universities all over the nation have taken the initiative to retain students and assist them both academically and socially before their first semester in college.

BYU recruits minority students who are going into their senior year in high school to spend a week on campus preparing for the ACT test and applying to colleges. The program called SOAR, or Summer of Academic Refinement, attempts to help students who are first-generation and come from low-income backgrounds. In 2016, a third of the students would be the first of their family to go to college.

Jodian Grant, 22, from Sicklerville New Jersey is a junior studying Communication Disorders. Her parents are first-generation immigrants from Jamaica. Grant said she was motivated to excel in her studies by her parents and wants to “give back” to her immediate family and those in Jamaica. (Photo courtesy of Jessica Banuelos)

Volunteers and faculty members who work with high school juniors and seniors have seen great transformation in future first-generation college students as they become familiar with college.

BYU senior Sadie Nielsen works as a volunteer for Teen’s Act which is a nonprofit organization based in Provo that’s dedicated to helping upperclassmen students academically. For the past five months, Nielsen has gone to Provo High School several times a week working with seniors who are now preparing to attend college classes this coming fall semester.

“They’re definitely a lot more excited now that they know. Even though some of them are staying close by like at UVU, they are excited to have independence and that they have made it this far,” Nielsen said.

##################

Tsosie remembered those tears and heartache in her dorm room on her last day at BYU as a 19 year-old. Years after dropping out, Tsosie decided to return to BYU in May 2003 to complete her bachelor’s, only this time she felt better prepared and knew how to overcome her stumbling blocks.

“To finish my undergraduate, I felt that I wasn’t given a fair shot,” Tsosie said. “I can’t blame the school or blame the system. I have no one to blame, just the unfortunate situation in life. Me not finishing, that wasn’t a true reflection of who I am. I just wasn’t given the proper tools. I went back to prove to myself that I wasn’t a failure.”

The Education Trust analyzed 255 colleges, from years 2003-2013, and discovered graduation rates for minority students, which were 6.3 percent, rose slightly more than white students at 5.7 percent.

While experiencing Round Two of her undergraduate endeavors, Tsosie understood what was required in order to succeed. She was a completely different person academically and in 2007, Tsosie became the first college graduate of her family.

Mari Tsosie Alvarado now owns her own law firm located in Utah. She is married and has 4 kids, 3 of which have graduated high school early. 2 have studied at BYU.

Today, Tsosie sits in her downtown office in Provo, with not only a BA on her wall but also a JD as well. She now works as an immigration, criminal law and family attorney. Meanwhile her kids have successfully navigated through their time at Brigham Young University — the same campus their mother struggled on years before.

Naataanii Tsosie, the eldest child of the Tsosie family, uses his mother’s determination as a source of inspiration.

“If I could put it in one phrase, I would say “no excuses”, so when there’s something that needs to be done, you just do it,” Naataanii said.

That’s the product of your success as a first-generation. They are our legacy. Mari Tsosie

Although for a moment, she felt defeated back when she was 19 years old at BYU, Tsosie proved to herself that she was a fighter. Her personal mantra, “Get through today, you can quit tomorrow,” has buoyed her throughout every challenge she has faced in life as a young child and all the way through adulthood as she now helps the Hispanic community in her law profession.

Thanks to her efforts and struggles, as a first generation minority college graduate, Tsosie paved the path of success to be smoother for future generations.

“My children are second generation,” Tsosie explained. “They know how, because we’ve walked the steps that were needed in order to succeed. That’s the product of your success as a first-generation. They are our legacy.”