BYU alumna Leila Tyltina’s family in 2014 was driven from their home in Makiivka, Ukraine by invading Russian soldiers. Eight years later she and her husband Alex Tyltin watched from their Wymount apartment in Provo as Russia advanced further into their home country.

This time, they went back to Ukraine.

Every morning they would scroll through the latest news updates, looking for places and faces they recognize. Alex said he looks on the Kyiv telegram channel every day to see if his childhood apartment building in Svyatoshyn, a northern suburb of Kyiv, is still standing.

“It makes it very emotionally difficult for us just to have this unknown,” he said.

The Tyltins have been in the states for 10 years, but they had family and friends in Ukraine when the conflict escalated. Leila’s parents were living in Irpin, a suburb of Kyiv that became a major battleground in the fight for the capital of Ukraine.

Leila’s parents got out before Russian troops decimated the city, but not everyone was so lucky. Leaving behind their jobs, school and their three children, the Tyltins booked a trip to the Ukrainian-Polish border to help refugees escape.

Personal connections to a faraway war

For the Tyltins, like many Ukrainians, the war didn’t start in February — it’s been going on since Russia invaded parts of eastern Ukraine in 2014. Seeing their family and friends flee Russia’s advances in 2014 played a major role in their decision to go help.

“We went there because we knew that there were a lot of people who were trying to just get to safety, just like our parents,” Leila said.

For the Tyltins, watching the conflict unfold on the news was personal. Referencing the end of days prophecies in scripture, Alex said everything happening in Ukraine was more than just “rumors of war” in faraway lands — it was real.

“We feel it,” he said.

Alex exchanges birthday messages on Facebook every year with a cousin in Ukraine. A few weeks ago he woke up to a very different kind of text from that cousin asking if he would chip in to help them buy bulletproof vests.

“That’s a very different narrative than ‘Hey Happy Birthday,'” he said. “It’s not some message that you want to get from your family members.”

As their friends, family and fellow Ukrainians were “going through hell,” the Tyltins realized they couldn’t stand still and booked plane tickets.

When Russia advanced its invasion on Feb. 24, volunteers came by the hundreds to help fleeing Ukrainians. The Tyltins planned to go a few weeks later to make sure the border would still have volunteers after the initial group left.

Arriving on March 18, the couple found that refugees came in waves. The first wave, Alex said, were people living close to the border who had resources to get out while it was relatively safe and the fighting hadn’t spread far. The people in the second wave had a much different story.

“The stories we heard from people,” Alex said, “almost everybody sounded something like this: ‘We were not going to leave until they started bombing our village.’”

Millions of people — including Leila’s parents — fled their homes because of Russia’s attacks. High rises that once housed upwards of a thousand people have been leveled by Russian missiles, leaving survivors with nowhere to go.

“That’s not what brothers do to each other.”

Leila Tyltina

Leila said although it was good many people have been able to get out, it doesn’t change the fact their cities have been destroyed and their lives and identities targeted.

“For the longest time I thought that we are like similar countries and similar nations,” she said. “I don’t dare to say brother nations anymore, because you know that’s not what brothers do to each other.”

Leaving the men behind to fight, groups of women, children and the elderly arrived at the border with harrowing stories and grocery bags filled with few possessions — and without their husbands and fathers.

Getting to work

When the Tyltins arrived in Ukraine, there was plenty of work that needed to be done.

Near the western border of Ukraine, people were getting stuck for days at refugee centers while they waited for a spot on a bus. The Tyltins planned to help drive refugees across the border in a rented nine-passenger van.

They said they quickly recognized most people needed much more than a ride. After arriving in a new country, many Ukrainian refugees were finding that crossing the border was only the beginning.

“So they feel now ‘we are safe,’” Alex said of the refugees, “‘but we have nowhere to go.’”

Instead of following their original plan of shuttling people across the border all day, Alex and Leila focused on meeting each group’s unique needs.

For one family, it was a good night’s rest and a shower in a Warsaw hotel. Another needed help communicating with a host family. Some needed spring clothes to replace their heavy winter gear, and others just needed a listening ear.

Suitcases at the temple

One experience stood out from the rest. At one refugee center, the Tyltins found a family of six that had waited four days for a bus that was always coming tomorrow. Thanks to the Tyltins, the family finally had a ride to Germany.

As they loaded their van, the Tyltins noticed this family, like many others, didn’t have a suitcase to put their things in and were using shopping bags.

Leila contacted a former missionary living in Germany and asked if members of the Church had any suitcases to donate. They would be driving back to Ukraine through Germany the next day, and could pick up any donations along the way.

In six hours when the Tyltins arrived at the Freiberg Germany Temple they found a pile of suitcases from members waiting for them to take back to the border.

Criticism of the global response

Leila said she “vividly” remembers the global reaction when Putin annexed Crimea in 2014: concern and solidarity, but no active support.

This time around, she said she was afraid the countries that could help would have the same reaction.

The discussion around foreign aid to Ukraine has been complicated as countries navigate treaties, NATO membership and threats from Russia. Since Ukraine is not a member of NATO, the U.S. and other countries have sent weapons and humanitarian aid to Ukraine, but no troops.

With frustration in her voice as she spoke of Ukraine’s struggles on the world stage, Leila cited a little-known promise made to her country: the Budapest Memorandum.

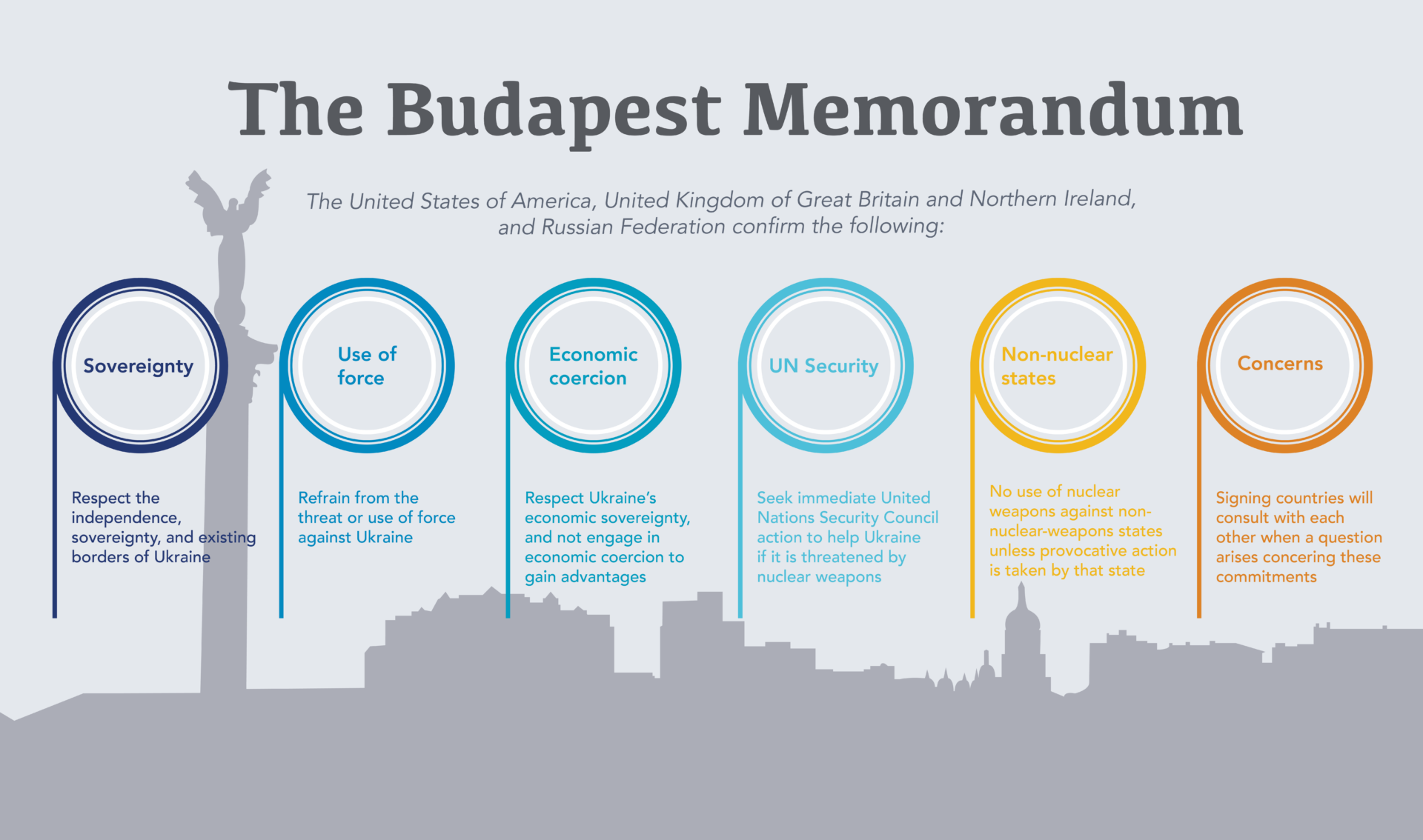

In 1994, the United States, United Kingdom and Russian Federation signed the Budapest Memorandum. These three countries offered six assurances to Ukraine in exchange for giving up the large nuclear arsenal stationed there at the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Unlike a treaty, the memorandum is not legally binding. It’s a political agreement with a promise, but not a contract with a clear way to enforce it. The security guarantees Ukraine was promised in the memorandum relied heavily on the signatories taking their commitments seriously.

Leila said the countries involved have sent a clear message about those promises: it’s just a piece of paper.

“You’re going to wait and watch our children being killed and our women being raped, just because these are not your women, and these are not your children?”

Leila Tyltina

“We’re not good enough for you to protect us?” she asked in response to the lack of help. “You’re going to wait and watch our children being killed and our women being raped, just because these are not your women, and these are not your children?”

Going forward

After returning to Provo on April 6, the Tyltins are still looking for ways to help and they are encouraging others to do the same. “There is definitely more to be done,” Alex said.

Depending on how the situation develops, they’re hoping to go back later in the year.

For those looking to do something locally, they suggest sending money to trusted organizations and people purchasing supplies and food. They mentioned opportunities to sponsor refugees as they resettle, allowing them to stay in countries like Poland and Lithuania where the language won’t be as much of a barrier.

To connect with the Tyltins about ways to help, contact Alex through his email: .