Grace Lund was finishing her last semester at the University of Utah when she was let go from her retail job. It was March 2020, and by June 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic took work from over 20 million Americans.

“I didn’t have another choice,” Lund said. “I applied for unemployment immediately.”

Lund stayed on unemployment benefits while receiving a $600 stimulus along with her unemployment check each week. “I was making significantly more on unemployment,” Lund said. At her retail job, Lund’s hourly wage was a few dollars above Utah’s $7.25 minimum.

Filling out the unemployment forms was a simple process, so Lund did not have a difficult time receiving her unemployment benefits. She does not believe surviving off unemployment benefits is a sustainable lifestyle though and she is now working again.

Unlike Lund, many Americans have still not re-entered the labor market. Employment rates in the U.S have not recovered since the pandemic disrupted the economy.

Utah’s unemployment

The Department of Labor reports that unemployment rates reached a high of 14.8% in April 2020. The unemployment rate the previous April was only 3.7%. The unemployment rate in the U.S. still sits a few percentage points above average.

“Like most places around the country, there is a labor shortage in the Utah labor market. There are probably lots of reasons for that. COVID-19 is behind lots of those reasons,” BYU labor economics professor Brigham Frandsen said.

Frandsen shared a few reasons for the poor unemployment rates brought on by the pandemic. Some parents, Frandsen explained, left the workforce to stay at home with children whose school was moved online during the pandemic.

Another possibility Frandsen suggested is some Americans might still feel hesitant about going back to work. Those who are nervous about getting infected have access to generous unemployment insurance and stimulus checks. These government benefits can help Americans make financial ends meet for an extended period, allowing them to stay out of the labor market.

In Utah, residents seeking unemployment insurance can receive 94.9% of their average weekly wage plus a $300 supplement. The average weekly benefit on unemployment insurance for a Utahn is $419. Utah has allocated $24,657,589 to unemployment insurance for 2022. This does not include the additional funds states receive from the federal government each quarter.

“If wages aren’t high enough, especially compared to outside options like stimulus, then that could be a reason why [workers] won’t join the labor force,” Frandsen said.

A minimum wage worker in Utah will earn $7.25 per hour, which adds up to $290 for a 40-hour work week. If an employee works for 52 weeks a year at 40 hours a week, they will earn $15,080 that year. However, it is unrealistic a worker will earn that much in a year on minimum wage because it requires no time off taken.

“What a labor shortage ultimately comes down to is what employers are offering isn’t enough to get [workers] to give up their outside options,” Frandsen said.

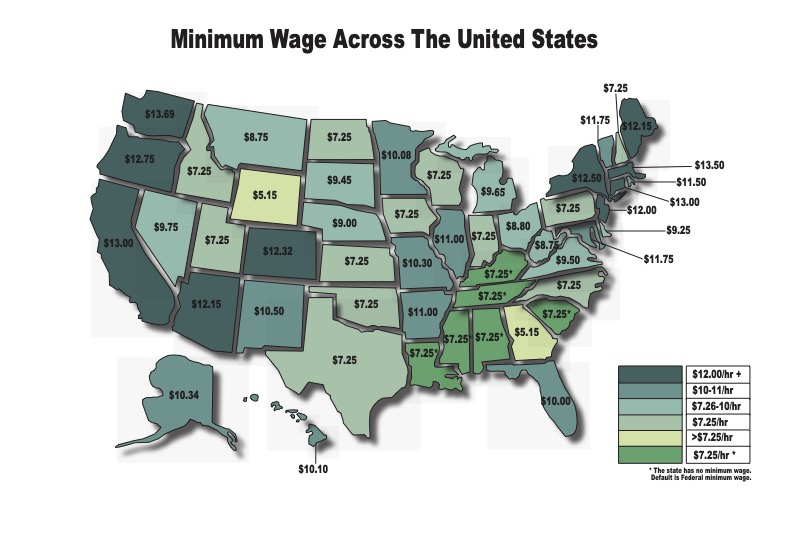

Minimum wage rates across the country

The federal minimum wage was last increased in 2009 from $6.55 to $7.25 to account for inflation. There are 29 states with minimum wages higher than the federal. Just 10 of those states pay a minimum wage of at least $12.

The Utah state minimum wage is $7.25, the same rate as the federal minimum wage. The average hourly pay rate for Utahns is much higher than the state minimum at $24.73 per hour.

In early 2021, Utah legislators proposed two bills to amend minimum wage laws in the state.

HB361 planned to increase minimum wage based on Utah counties and enact an annual inflation adjustment. The other bill, HB284, proposed to gradually raise the state minimum wage from $7.25 to $15 per hour by 2026. Neither bill passed the full legislature.

The amendments to the state minimum wage proposed in HB284 closely resemble the minimum wage ordinance passed in the city of Seattle in 2014. That year, Seattle began gradually increasing the minimum wage starting from $9.47 per hour. In 2021, the minimum wage in Seattle reached $16.69 per hour — more than double the minimum wage offered to Utahns. This makes the minimum wage in Seattle one of the highest in the country.

The Seattle minimum wage ordinance was closely researched in a study from 2014-2016 by a group of professors and students at the University of Washington. Among the group of six researchers were former student Emma van Inwegen and emeritus professor Robert Plotnick.

“Minimum Wage Increases, Wages, and Low-wage Employment: Evidence From Seattle,” was a paper they published that offered rare in-depth insight about the impact on workers when minimum wage is raised.

“The predominant result … was that for people who were making below the new minimum wage, so the effected workers, their hourly wages went up about 15% and that was slightly offset by the fact that their hours went down by about 3-5%,” van Inwegen said.

Plotnick and van Inwegen both explained those hurt most by the minimum wage increase were those looking for jobs who were not previously in the labor market. The researchers found most businesses chose to leave positions unfilled rather than lay off employees or cut hours.

“We [saw] a fairly substantial impact on what we would call new entrances to the labor market. They are people looking for jobs that would have been there but no longer were,” Plotnick said.

Both researchers described how increasing the minimum wage — especially by a low percent — does not produce any catastrophic impacts on workers or businesses. They also write that there are probably better ways to help lift workers out of poverty than raising the minimum wage.

By the end of the study, Plotnick developed a new outlook on minimum wage increases. “I stopped being such a big fan of it,” Plotnick said. “The research shows there’s small effects on employment, there’s some small gains on earnings, but it’s not going to transform people’s lives in terms of poverty. It’s not going to ruin companies, so at the end of the day it was almost kind of a wash.”

Americans on minimum wage

In the U.S., 1% of workers over the age of 25 earn at or below the minimum wage. By comparison, 5.1% of employed U.S. teenagers, ages 16 to 19, earn at or below the minimum wage.

“When you look at who earns the minimum, sure some of them are parents or older folks, but a lot minimum wage workers are teenagers at their first job,” Plotnick said.

Hannah Bridge, a 17-year-old Salt Lake City resident, was paid minimum wage this summer working at a shaved ice stand. Bridge’s tasks included taking orders, making the shaved ice and handing out orders to customers.

“It was a really easy job,” Bridge said. “But if it had been harder and more busy the pay wouldn’t have been worth it.”

Bridge worked a second job over the summer because she did not feel she was making enough on minimum wage.

“I wouldn’t work another minimum wage job,” Bridge said. “The pay is so low and things are more expensive than what you are getting paid.”

Like most U.S. teenagers making a low wage at their first job, Bridge was not the principal earner in her household and only earned money for personal purchases.

“Most minimum wage workers are teenagers or young people, not the principal earners for households,” Frandsen said. “So they’re the people that will be most affected and whether or not they are under the poverty line since they are not the primary breadwinners for their family will not be hugely effected.”

The bigger challenge for families is whether one or both primary breadwinners have the skills to earn more than the legal minimum.

Wages for skilled labor

“I’m pretty picky with the people I hire,” said Lex Maynez, a BYU student who owns and operates Sad Boi Thrift in Provo.

Maynez pays more than Utah’s minimum wage rate because he is looking for employees with a specific set of skills.

“I pay depending on performance,” Maynez said. “I am definitely willing to pay more if [an employee] can find stuff I can sell at the store. It requires a certain eye.”

The approach Maynez takes in hiring employees parallels the data found in the Seattle study. When business budgets took a hit by the minimum wage increase and they needed to cut back on employees, they let go of workers with the least skills.

“Less experienced workers bore the brunt of the impact, which kind of makes sense theoretically,” Plotnick said. “If you are going to get rid of someone, you will get rid of someone less experienced with your operation.”

Outlook for wages in Utah

Minimum wage has not been adjusted for inflation in over a decade. The value of $7.25 has decreased by over $2 in the past 12 years. In today’s economy, $9.29 will buy as much as $7.25 did in 2009—the last time the federal minimum wage was increased.

In 2009 you could buy an iTunes song for 99 cents — they now cost $1.29. Even Dollar Tree decided to raise its prices in late 2021. After 35 years, the iconic $1 deal was raised to $1.25.

In nine states, including Colorado and Montana, minimum wage is adjusted annually based on cost-of-living index in order to keep up with inflation and preserve purchasing power.

“I think it would be great if [minimum wage] kept up with inflation,” van Inwegen said. “If the minimum wage kept up in terms of what you can buy with a dollar, then the minimum wage should be much higher now.”

There is a long list of reasons why the minimum wage hasn’t increased nationwide.

“It’s all politics,” Plotnick said. “If [increasing minimum wage] is not all that successful in terms of raising people at the bottom, maybe there are some other policies we can pursue that would be a better use of our political capital.”

If Utah wants to help pull people out of poverty, there could be more effective strategies than raising the minimum wage, Plotnick and Frandsen both suggested. Some of these possibilities are expanding the Earnings Income tax credit, providing subsidies for education and/or providing better childcare services to working parents.