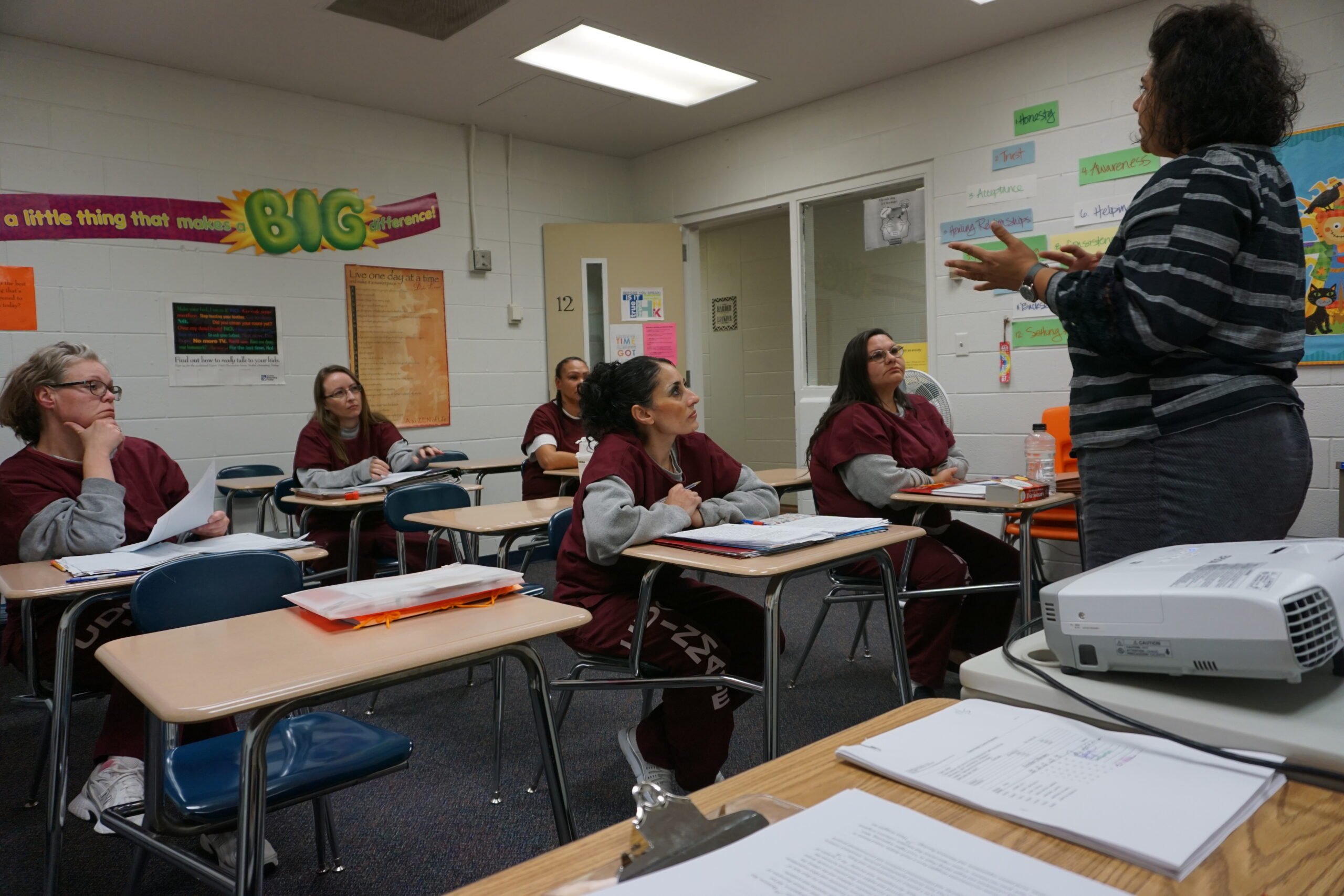

BYU students and professors are volunteering to teach in prisons as part of the University of Utah’s Prison Education Program.

The Prison Education Program seeks to bring social transformation and educational equity to Utah prisoners. This goal is accomplished through advocacy, research and by providing on-site college curriculum to prisoners. The program provides college classes for credit to two groups of students incarcerated in the Utah State Prison in Draper.

“I’ve had a long-standing interest in, I guess alarm, about how badly we do incarceration in the United States,” BYU history professor Matthew Mason said. After seeing other colleges provide educational programs to incarcerated individuals, Mason found Utah Prison Education Program and started teaching inmates.

Utah Prison Education Program was started by a group of 10 undergraduate honors students and professor Erin Castro at the University of Utah. Castro, the program director, came to Utah from the University of Illinois, which has a very strong prison education program. When she noticed the lack of a similar program in Utah, she saw an opportunity and decided to take advantage of it. With the help of her honors class, Utah Prison Education Program eventually came into existence.

Since partnering with BYU, Castro has been delighted and humbled to see the results of efforts from BYU professors and students.

“I am just in awe of the kind of work that they do with our students and the courses that they teach,” Castro said.

Castro also expressed her hope for the program’s future and BYU’s role in its growth. “I am so thrilled that we have this partnership and I would love to see it grow and see BYU continue to support this partnership,” Castro said.

For volunteers, the program provides an actionable way to combat the U.S. incarceration system. Incarceration rates in the United States are the highest in the world at 639 per 100,000 individuals. The next countries to follow are El Salvador and Turkmenistan at 566 and 552, respectively. These numbers represent an “alarming state of affairs,” Mason said.

Since volunteering, Mason has had the opportunity to teach history to inmates. In fall 2021, he taught the BYU course HIST 220, which covers U.S. history through 1877. Generous donors paid for the students in the class to receive university credit through BYU, the first time this was able to be done, he said.

“Once you get rolling, it’s just a class and it’s one of the most fun classes I’ve ever taught,” Mason said. He tries to go to the prison to teach his students once a week. “I have to under-prepare the amount of material because I know they’re just going to have all kinds of great questions and comments and so forth that are going to help fill the time.”

Mason and other volunteers have also encountered challenges along the way, especially since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. History professor Christopher Hodson described a state of “being at the mercy of the Utah Department of Corrections, which often is not especially well set-up to handle higher education in prison.”

Teaching is made difficult by the complete lack of internet access, Hodson said. Professors and TAs have to pass multiple security checkpoints to get to their students. Textbooks have to be approved before being brought into the facilities. In fall 2021, classes were canceled for a couple weeks because of a COVID-19 outbreak within the prison.

Hodson also described a time when he and his TA were trapped inside the prison for a couple of hours before his students had even arrived because someone within the prison had an episode that brought out the facility’s SWAT team.

One day, Hodson told his students he was meeting with the donor who was funding their tuition for the semester. He asked the students what they would like him to tell the donor.

“That discussion with those incarcerated students totally made it worth my time because it revealed a lot about their motivations,” Hodson said. “They just want a shot, a shot at not just getting a degree so you can get a job, but to actually become a more complete person.”

Hodson went on to explain how many of these people were “essentially funneled into the carceral system” from a young age.

“These are people who are well aware that they have committed crimes for which they are being punished and they get that they are taking responsibility for what they have done,” Hodson said. “At the same time, it is often the case that for most of us at places like BYU, we’ve never experienced anything remotely like what these guys experienced as young people.”

Julia Hecht, a senior studying Spanish teaching, applied to be a TA for the program this last fall semester after reading lawyer Bryan Stevenson’s book “Just Mercy” and learning about the high rates of recidivism in the U.S. Hecht said the criminal justice system seems purely punitive and not rehabilitative.

“I think that offering education in prisons gives people the opportunity to learn and change, and it also gives people a chance to progress and I think everyone deserves that no matter where they are,” she said.

Hecht had the opportunity to speak to an alumna of the program who expressed her gratitude for the volunteers and the program.

“She said that the fact that people were willing to come in and volunteer their time to educate her made her feel like there was still hope and that she could still make a change and make a difference in her life,” Hecht said.

Social science student Katie Rolfson was also a TA during fall 2021. On one of her first days, she had a memorable experience with one of the students. The student shook her hand as she was leaving and said, “I just can’t tell you how relieving it is to have a place where we can have intellectual conversations. We just don’t get that here.”

Rolfson reminds herself of this encounter as she prepares discussion questions and material for the students, knowing what these students really want is an opportunity to simply talk and discuss topics on a higher level.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story did not correctly say it was the University of Utah’s Prison Education Program and it has since been corrected and updated.