New research by the Utah Women and Leadership Project focuses on how the COVID-19 pandemic affected women in Utah with a special emphasis on caregiver experiences.

Utah Women and Leadership Project Director Susan Madsen led the research. She said the organization’s mission is “to strengthen the impact of Utah girls and women.”

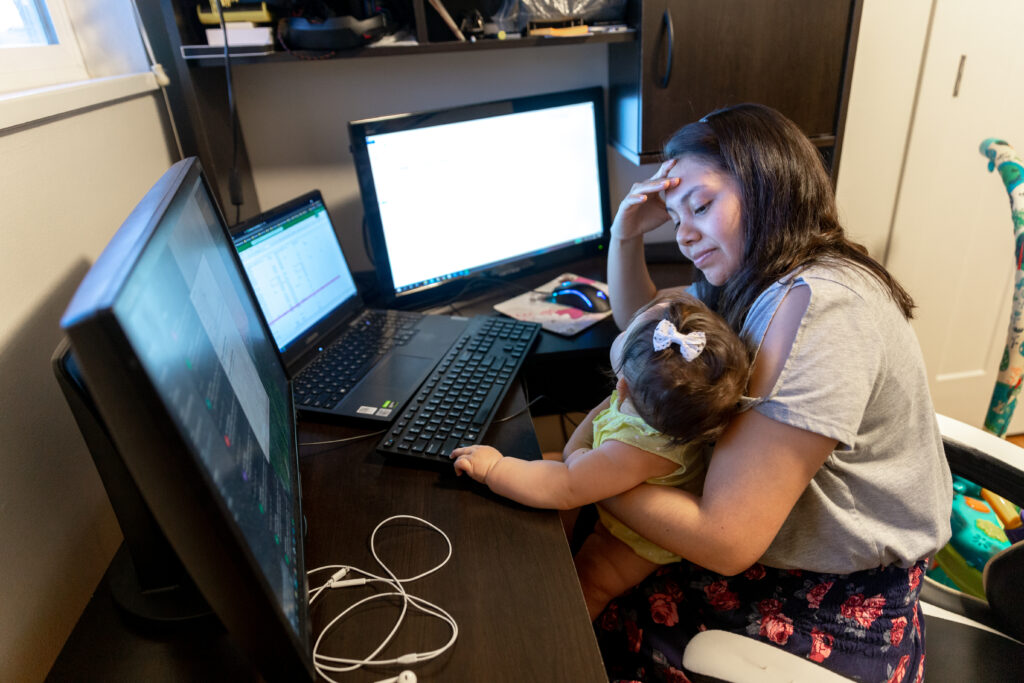

Madsen led her research team in surveying a sample size of 3500 women across Utah. Their research has been compiled into six different reports. The first report featured working women facing unsustainable labor loads while managing both their home and work responsibilities.

The second and third reports accounted working mothers feeling guilt as both parents and employees and describe the lack of support on both fronts, but especially from their spouses as responsibilities at home increased.

The fourth report discussed parents facing childcare hurdles at a desperate time including having difficulty finding care, not feeling safe utilizing care or no longer being able to afford care.

The fifth report highlighted the child care industry’s plummet in enrollment, increased safety protocols and costs, and a progressively unstable workforce. Child care workers described the grief felt for not being recognized as “essential” when childcare centers weren’t forced to close like schools.

Working respondents facing the stressful reality of caring for their own children along with caring for older, at-risk adults such as their own parents was the focus of the sixth and final report. Older respondents described stepping in to care for their grandchildren.

Women of all different incomes, geographical areas, races and ages were surveyed. Madsen said there were consistent themes found throughout the research of women’s “struggle to juggle.”

Women who primarily have a caretaker role reported difficulty managing both home and work responsibilities. This conflict led to working more hours and catching up on tasks late into the night to make up for lost time spent caretaking and helping children with homeschool, Madsen said.

The research showed many surveyed participants began caring for older, at-risk adults such as their own parents, while older participants described stepping in to care for grandchildren. Some respondents were caretakers of both young children and their parents, further creating stress and imbalance.

Madsen said it was striking to her that 24% of women with partners said their spouses or partners were supportive. Seventy-six percent reported their spouses were not supporting or helping them in handling childcare or employment issues.

She also said she was deeply saddened by 10% of their sample size reporting they were experiencing or were deeply afraid of domestic violence in the home.

The home was not the only place where women struggled to find balance or assistance. Madsen said maybe half the women in their sample size reported their organizations and employers were not helpful, understanding or supportive of them as they tried to juggle all their new responsibilities.

“The other half did share amazing stories of bosses and companies who helped, talked with and encouraged them. We need to see more of that,” she said.

Human resources senior Megan Weaver worked from home throughout the pandemic. “I think one of the positives of the pandemic was that employers saw working from home could be done. Before, companies were more against it,” she said.

Many people thrive from working at home or can create a better work-life balance if they don’t have to go into the office every day of the week, she added.

Utah Women and Leadership Project Associate Director Marin Christensen was the lead researcher and author of the qualitative COVID-19 briefs for the project. She said the team’s findings on mothers feeling extreme guilt were what surprised her the most.

“We found there was just so much pressure to meet expectations from family and employers,” Christensen said. “Women felt guilty about possibly not being there for their children if they were working even more and then feeling guilty for not being good employees if they were needed more than ever at home.”

As someone who doesn’t have kids, Christensen said these were not feelings she could understand from her own pandemic experience but that it was extremely eye-opening to learn what women were going through.

Madsen truly believes women are doing the best they can to be on top of all the different roles they play.

The project’s research reports the girls and women surveyed continuously felt they were letting people down and felt guilt at quite a serious level.

“The stories they told us were heartbreaking, I had tears reading them. These good women have repeatedly found themselves in no-win situations, especially single mothers,” Madsen said.

Christensen hopes the research helps women not feel alone and know there are others who understand what they are going through.

“I don’t think the system supports working moms and women enough; they are entitled to more support. I would encourage them to come to the (Utah Women and Leadership Project) to get engaged alongside us,” Christensen said.

The Utah Women and Leadership Project website is available for those who would like to learn more about the group’s research, events and resources.