Gender discrimination can influence how motivated women are to pursue careers in STEM, BYU family life professor Adam Rogers told students during the Global Women’s Studies Colloquium on Nov. 20.

Rogers said while women earn 60% of bachelor’s degrees, men outnumber women in most science, technology, engineering and mathematics degrees and jobs, including jobs in engineering, medicine and university faculty.

“As a society we have a very vested interest though in giving girls and women equal opportunities to pursue and thrive in STEM careers, and this is important for narrowing the gender pay gap, enhancing women’s economic security, ensuring diverse and talented workforces, and also preventing biases and blind spots in the products and services that these fields produce,” he said.

Rogers said the origins of the gap between men and women in STEM are complex. As a developmental psychologist his research focuses on the role of sexism and discrimination in women’s educational choices.

“Early life experiences with sexism undermine girls’ interests and motivations in STEM,” he said. “The gender gap in STEM is already well underway even in early childhood and adolescence.”

Rogers explained that by the time children reach the age of 6 or 7, they have already built gender schema, or mental libraries of information about what it means to be a specific gender. Like a color filter on a camera, these beliefs about what is and isn’t appropriate for a specific gender shade the way children perceive the world around them, Rogers said.

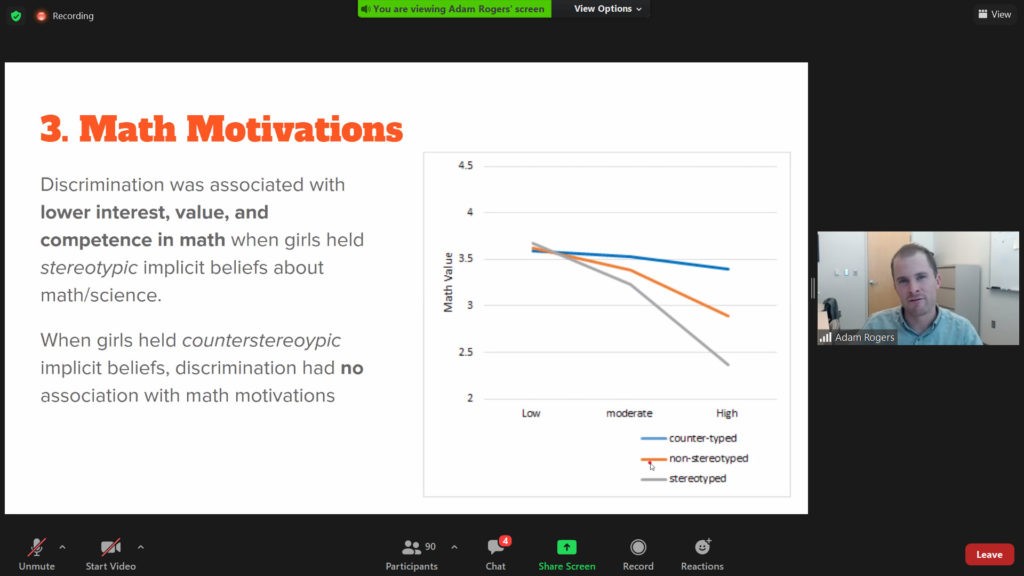

According to his recent research, titled Project AHEAD, Rogers found that girls who experienced gender discrimination in high school — which he defined as unwanted romantic attention, demeaning jokes and insults — were less likely to feel like they belonged at school. He also found that when faced with gender discrimination, high school girls with internalized stereotypes (such as boys are better at math) had a lower level of interest, value and competence in math than girls without those stereotypes.

Rogers said there are two general responses in society to try to alleviate harmful stereotypes that keep girls from pursuing STEM careers: One is to repudiate the notion that girls don’t belong in STEM, and the other is to “pinkify” STEM — or rebrand engineering, math, physics, etc. to appeal to girls. Rogers cited the example of Lego Friends, which encourages spatial play in little girls by repackaging Lego in pink and purple, or the European Commission’s “Science: It’s a Girl Thing” campaign.

Rogers said these attempts to repackage STEM have been proven to ultimately decrease girls’ interest in fields of science, mathematics and technology and increase their draw to hyperfeminized products and stereotypes.

To combat gender stereotypes, Rogers recommended that teachers not reinforce the idea that gender is relevant to academic success because, according to Rogers, it isn’t. For example, he said teachers should refer to their students as “children” or “students” rather than highlighting gender by saying “boys and girls,” quoting a study that showed students referred to as “boys and girls” developed more gender stereotypes and aversion to interacting with members of the opposite gender.

He also said parents, especially parents of daughters, should raise their children with feminist ideals.

“Feminism is an empowering ideology for many girls and women because it provides girls with a framework for making sense of the sexism they will inevitably experience. In this way, feminism provides girls with a framework to help them identify harmful gender stereotypes, make sense of these stereotypes, and pursue viable alternative beliefs, attitudes and behaviors,” Rogers said.

He added that teenage girls who understood feminism were more able to identify discrimination and cope with it. “As a result they are not as negatively affected by the effects of stereotyping and discrimination compared to girls who do not have feminism as a resource.”

The Global Women’s Studies Colloquium is held twice a month and is “a forum for discussion, intellectual development and scholarly collaboration among students, faculty and others interested in participating in a community of Women’s Studies scholars.” The next lecture is titled, “Classroom Characteristics that Increase Female Participation and Performance in the Life Sciences,” and will be held Dec. 4 over Zoom.