Shaun Roundy plunged a 9-foot aluminum probe into the churned snow searching for submerged backcountry skiers as he stood shoulder to shoulder with fellow rescue personnel. Flanking him, other search and rescuers did the same.

Another team scanned for clues below Roundy’s search line — a glove, a mitten, a ski pole — anything that might indicate a person buried nearby. A different group scanned the slopes for signs indicating whether another avalanche could cascade onto the rescue team.

Roundy repeatedly plunged the probe deep into the snow, aware that with each passing minute odds of rescue decreased monumentally. Nearby, other responders clutched shovels and waited.

The preceding is standard each time the Utah County Sheriff Search and Rescue team receives an avalanche call, which generally happens one or two times a year, according to Roundy. Other teams, particularly those in Salt Lake County, tend to respond to more avalanche calls.

Sometimes the search and rescue team has to return on a different day to recover the body, but the team generally only leaves after the victim’s odds of survival decrease to almost nothing, Roundy said.

Other times, if conditions are too dangerous, the search and rescue team won’t make it to the avalanche site until much later.

“Avalanches are particularly tricky,” Roundy said. “The number one rule is never put your own life at risk because then you just become another victim. When there is one avalanche, there is likely to be more.”

After one 2009 avalanche, the team wasn’t able to recover the victims’ bodies until several months later in March, he recounted.

Roundy said most avalanches are triggered by novices who don’t know what they are doing in the backcountry.

The majority of avalanche victims were engaging in backcountry activities before being submerged. Once buried chances of survival are relatively low, but researchers have developed new technology to aid rescue personnel like Roundy in recovery as well as help backcountry skiers locate submerged party members.

Backcountry adventurers venture into sparsely traveled parts of the wilderness for outdoor recreation, typically via snowmobiles, skis or snowshoes. Utah — with its toted powder and large, frosted peaks — is famous for its backcountry.

Outdoor lifestyle company Osprey wrote that Utah is one of the top eight U.S. destinations for backcountry skiing. News site CBS DC called Utah the best backcountry skiing destination.

According to Roundy, backcountry activities can be dangerous, unruly and sometimes unpredictable.

Avalanches are voracious. Once triggered, they cascade down mountainsides, tear up vegetation — even large trees — and sweep up anyone or anything in their path.

People triggered a total of 146 avalanches during the Utah 2017-18 winter season. Of the 146 incidents, 39 people were injured and 16 buried. Zero were killed — an anomaly, according to KSL. Until 2017, an average of four people died yearly.

“About ten years ago or so there was a pretty big need for avalanche education,” Roundy said. “Since then (the Utah Avalanche Center) has done such a good job of getting the word out and educating people about which areas to avoid, what equipment to bring and what to look for.”

According to Roundy, the Utah Avalanche Center’s efforts combined with favorable weather conditions have led to fewer recent avalanche-related deaths.

Roundy said search and rescue team members participate in avalanche training annually. However, every four years, they are tested by other search and rescue teams.

During training, instructors reiterate that search and rescuers will most likely use what they learn to rescue somebody in their own party and not necessarily somebody else’s, he recalled. When a person calls in about an avalanche, it takes a significant amount of time to deploy the search and rescue team up the canyon. There is a good chance that by the time responders arrive anyone buried will already have died.

“After 15 to 30 minutes, your chances of being alive and not suffocating are cut in half,” Roundy said.

Roundy said responding to avalanches is complicated.

“On one hand, its urgent,” he explained. “On the other hand, in the back of your head you might be thinking it’s probably going to be too late by the time I get there.”

Roundy said he never lets those thoughts deter him.

Backcountry skier Doug Farrer lost his friend from a backcountry avalanche in 2011.

26-year-old Garrett Smith was magnetic and gregarious, according to Farrer. He was an accomplished backcountry skier and owned an outdoor photography business where he did high angle video and photography.

“It was just such a loss,” Farrer said. “It was like having your favorite star in the sky go out that you can never, you know, see ever again.”

The Salt Lake Tribune reported that Smith was backcountry skiing in the Sanpete County area with his wife and several friends before he died from avalanche induced trauma.

Farrer said the group of skiers paused on the mountain to dig a snow pit intended to help them assess avalanche danger. As Smith and the other two men determined the snow was unstable and decided not to ski the area, a slab of snow gave way beneath the snowcat perched higher on the ridge. The three were swept down the mountain.

According to the Tribune, one of the skiers dug out another who was partially buried. Together, the two managed to pull out Smith, who was not breathing. The skiers administered CPR, but Smith died en route to the hospital.

After Smith’s death, Farrer said his confidence almost disappeared. Before the incident, he always felt like judging avalanche conditions was within his control.

“They did all the right things and they still got hit by an avalanche,” Farrer said. “His passing gave me a lot more respect for the outdoors and made me realize I need to be more serious about (the backcountry).”

Farrer stopped going into the backcountry alone and bought wireless transmitters and other backcountry gear. He started paying closer attention to daily avalanche forecasts given by the Utah Avalanche Center and became almost painfully aware of even the most minute chance of danger.

In wake of his friends passing, Farrer said one thing that he wants to convey to other backcountry skiers is to practice doing drills and repeating safety practices until they are second nature.

Farrer said avalanche courses are expensive, but necessary.

“You can’t prepare enough,” Farrer said. “At least by doing that you’ve taken the right precautions and done everything you can.”

According to Farrer and backcountry skier Trent Duncan, technological developments in the past decade have made the sport far safer.

Avalanche beacons, or wireless transmitters, are one of three critical pieces of equipment that individuals venturing into avalanche terrain should carry and know how to use, according to Duncan. The others are a shovel and a probe.

Beacons are worn under the clothing and transmit a signal that, when picked up by another beacon, can be used to approximate the location of a buried skier. A probe, like the one often used by rescue personnel like Roundy, is then used to pinpoint the buried person before digging can begin. Without this gear, there is a nearly zero chance of finding someone buried in an avalanche.

Skier airbags can also help keep someone alive if the person manages to deploy it before being completely submerged in an avalanche.

Duncan said he tries not to be out when the snow is reactive, which he believes is the best way to avoid triggering an avalanche. Before venturing into the backcountry, he always checks avalanche forecasts and local weather reports. Duncan said he also spends time researching how and why people died in the areas he plans to go.

In addition to daily updates about localized avalanche conditions and issuing avalanche warnings, the Utah Avalanche Center provides training, courses and resources so people who enter the backcountry can increase their odds of returning safely.

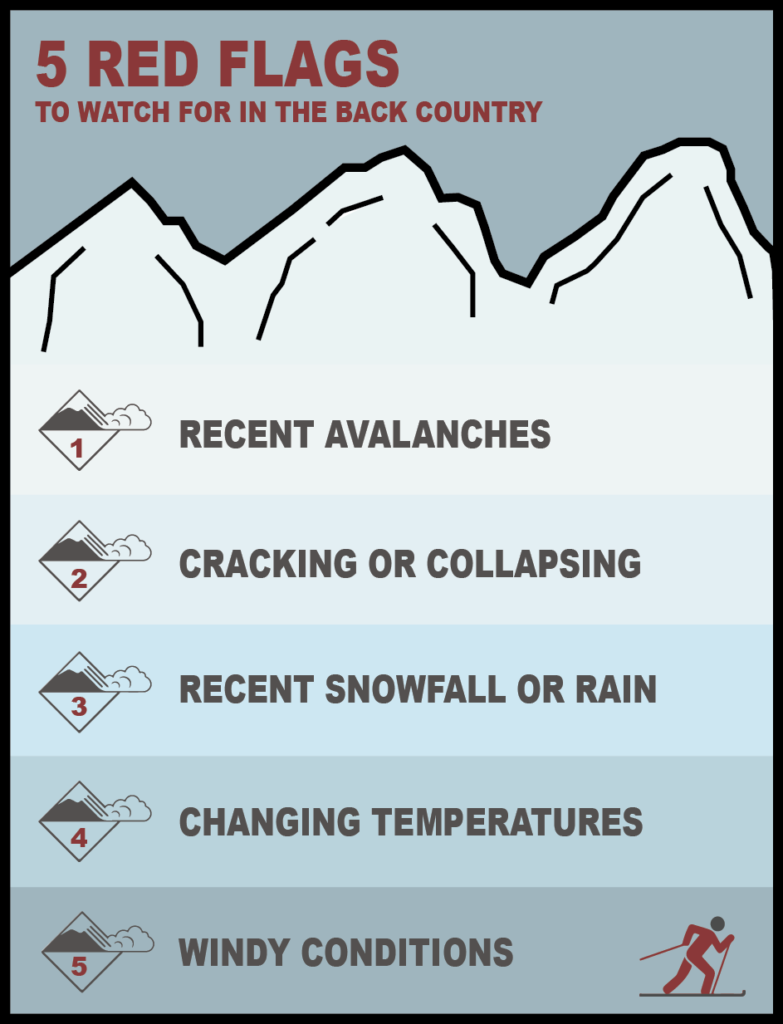

According to the Utah Avalanche Center, many people who enter the backcountry aren’t aware of the signs they should be looking for. The center in part exists to educate the masses about avalanches. Its online “Know Before You Go” program describes five red flags backcountry skiers should watch for.

The program advises anyone in the backcountry to look first for recent avalanches, and second, be aware that cracking and collapsing signify weak snowpack. Third, avalanches are often triggered when additional weight is added to an already stressed snow pack — which is why people are encouraged to be extra careful during recent snowfall or rain. Fourth, the program teaches viewers that wind can move more snow than a snowstorm. Snow drifts sculpted by wind sometimes indicate dangerous conditions. Finally, the program emphasizes changing temperatures can also lead to dangerous avalanche conditions.

Like Duncan, skier Josh Udall carefully analyzes potential dangers before embarking on any backcountry expedition.

The steeper the slope, the more likely the avalanche, Udall said. Snow slides naturally off extreme angles, and after adding the weight of a skier, the slab is even more likely to break. The danger zone lies between 30 and 45 degree angles, which Udall said is unfortunate as steeper slopes are intriguing and more exhilarating.

Part of the draw of backcountry activity is the thrill, knowing somewhere in the back of your mind how dangerous hurtling down the mountain can be, he explained.

It’s different for skiers like Farrer and search and rescue personal like Roundy because they’ve been personally touched by death. They’ve seen first hand how the backcountry’s striking beauty can turn deadly within seconds, Udall said.

For most backcountry adventurers, avalanches are a distant force. Distant, until they are not — and people don’t typically get a second chance to reevaluate their avalanche awareness once caught in one.

“The smartest people in the world are the ones that can control that appetite of skiing something really steep, yet turn around when things are too dangerous,” Udall said. “Sometimes their lives depend on it.”