See also “Fake news, propaganda spreads quickly on social media“

Although it can be challenging to defeat hackers and deceptive social media tactics, it’s still possible, according to BYU and UVU experts.

Prior to the 2016 presidential election, Russian government-backed hackers stole information from Democratic National Committee computers, according to CNN. The hackers proceeded to use this information to manipulate public opinion regarding Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.

However, J. Reuben Clark Law school professor Eric Jensen said cyber defenses are always improving, and the FBI often tracks potential cyber attacks on government organizations and businesses.

“The FBI will often find out something’s going on and will contact the company and suggest they look at their security systems,” he said.

The government can also extradite foreign hackers for punishment and use any data on the hack to prosecute them as criminals. “Once we get them in the U.S., the penalties can be quite severe, like decades in prison,” Jensen said.

In the event that a nation proves to be uncooperative in the extradition process, the U.S. can indict the hackers and register them with Interpol, Jensen said. If the hackers left their home country, they could be arrested in another nation.

Jensen also noted organizations work together to help prevent breaches and hacks.

“In the financial sector, institutions will often talk to each other. If one bank gets attacked, that bank will pass information to all the other banks so they can avoid the same type of attack,” Jensen said. “The same thing is true of electronic power grids and friendly states.”

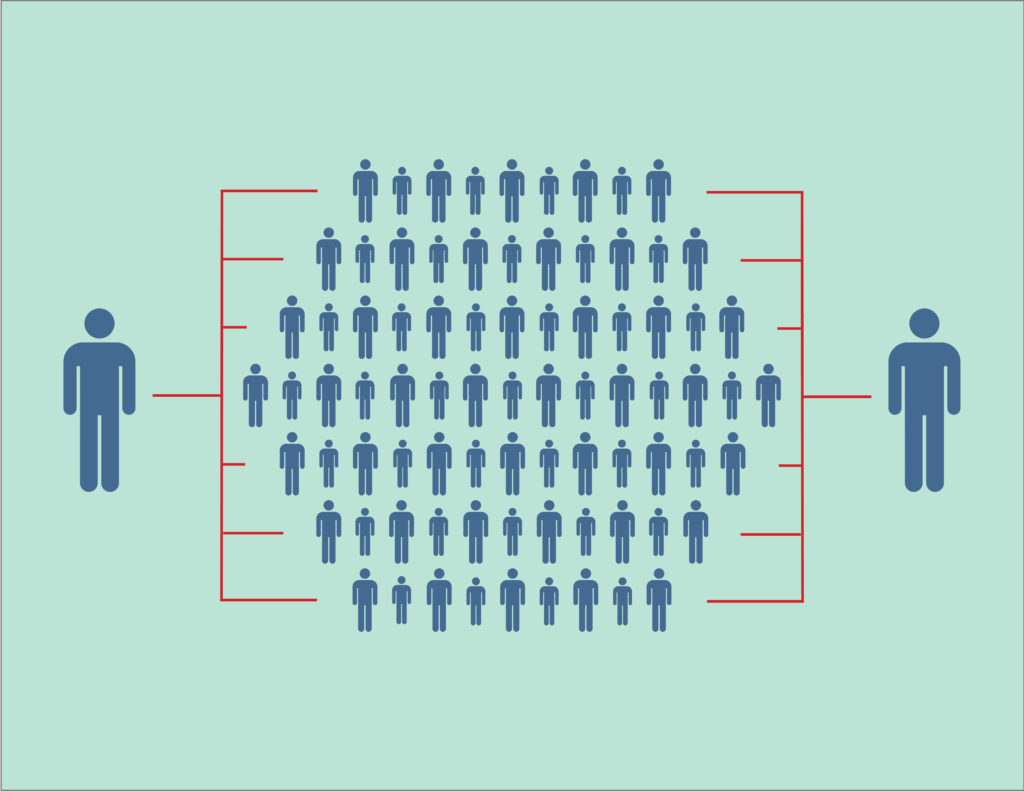

On social media, BYU YDigital Managing Director Adam Durfee said users are better suited to combatting fake news and misleading information. Facebook often has to sort through thousands of posts a minute, while platform users can more easily flag troubling posts on an individual basis.

“The ultimate responsibility for online literacy comes from users. Facebook polices about 293,000 posts a minute,” he said. “The responsibility doesn’t lie with the platform to police posts. The amount of posts users see is far less than 293,000 in 60 seconds.”

Election law attorney Audrey Perry Martin also said social media companies were “caught asleep at the wheel” during the election, which has led organizations to beef up their efforts to prevent misinformation that could influence voting in the future.

“They know if they don’t adequately self-regulate, Congress will do it for them. Facebook was taken to task by Congress,” she said.

Martin also said Facebook has specifically set up a “War Room” to monitor election activity on their site and they’ve introduced higher standards for political campaign registration. Martin noted hearsay that smaller campaigns have had trouble signing up for accounts and running ads.

Martin also said Facebook has set up archives for election and political ads with information that “discloses who paid for them and the demographics of those who saw the ads.”

J. Reuben Clark Law School associate professor Stephanie Bair also said disassociative behavior leading to cyberbullying and online trolling is a “relatively new phenomenon.” In order to fight this trend, Bair recommends social media users start with themselves and their own social media use.

“One thing each individual can do right now is take a close look at their own online behavior. Are they proud of their online interactions?” she said. “Would they feel comfortable saying the same things if the recipient was standing in front of them with others watching?”

Bair also said it’s important that people “think about the effects their words are having on others,” despite it being easy to say hurtful things to others from the safety of a computer or phone.

Durfee and UVU assistant professor and Chair of Communications David Morin both agree that social media users should develop online and media literacy to help fight misinformation and propaganda. Durfee recommended journalists and social media users both investigate sources to determine their validity.

Morin said political tension between the right and left has also led to social media echo chambers, which cause users to see and hear information suited to their beliefs regardless of the truth.

“We have to take a concerted effort to be a literate citizen. Follow people and organizations from the right, left and middle that are already established in terms of their credibility,” he said.

Morin also said social media users have “a wide variety of toolkits” to verify information, including Google searches and fact-checking websites. The biggest roadblock, however, is whether or not they want to make the effort.

“Verification is hard, it’s difficult. Most people don’t have the time. But today in the 21st century, it’s necessary,” he said.