Editor’s note: This story pairs with “Anti-Semitism incidents resurge in the US” and “BYU students of other faiths learn tolerance through marginalization.”

I grew up as one of the only Jewish kids in a small and conservative suburb of San Antonio, Texas. At times, it was a hard and scary experience, but I am also grateful for all I went through because it helped me become a better person. However, life wasn’t the easiest.

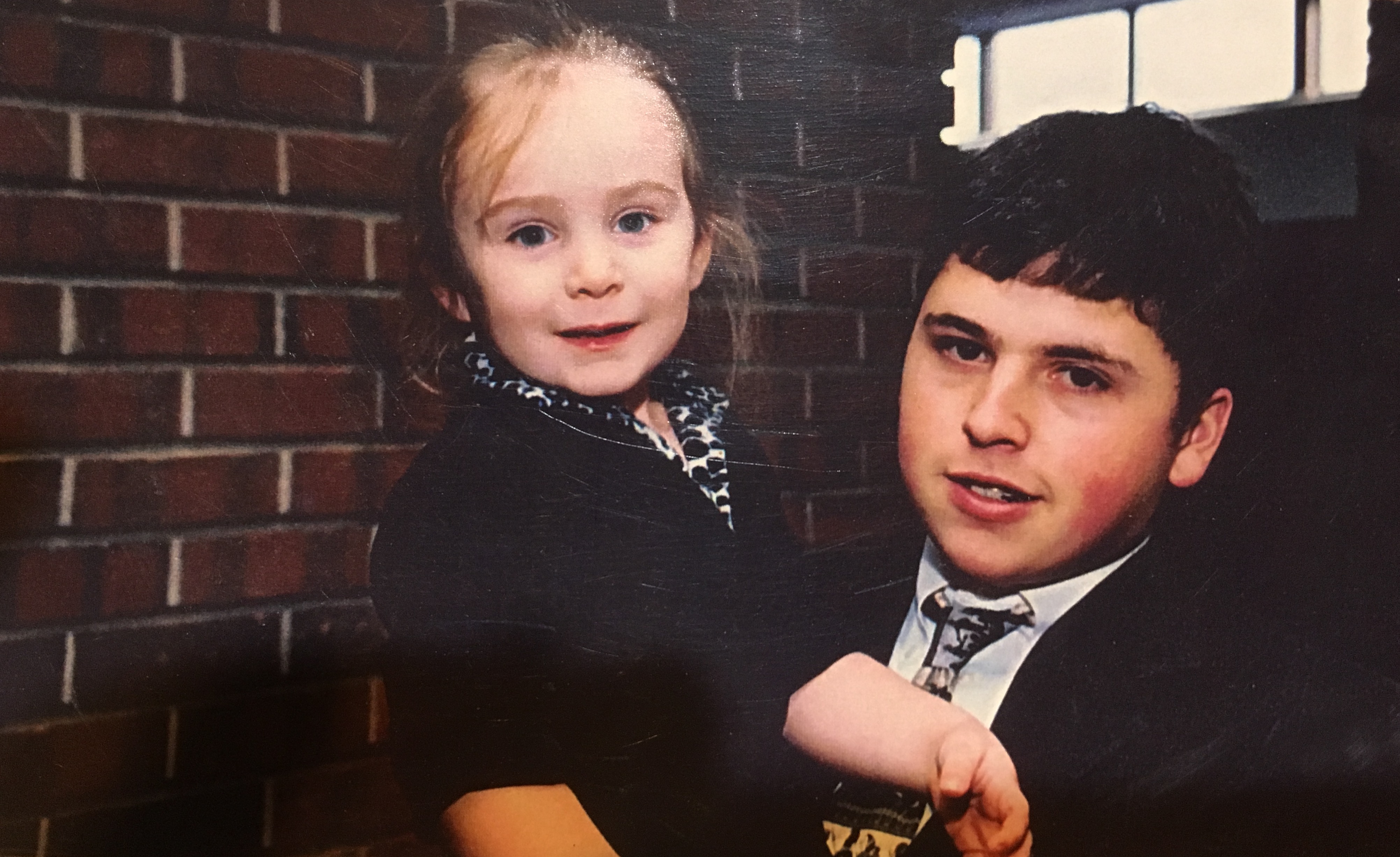

I remember bringing matzah to elementary school during Passover and getting weird looks from all my classmates. I remember being told I killed Jesus when I was in the first grade. I remember when my sister’s classmates told her to “go back to Auschwitz” and to “get in the oven.”

I also remember the mini Shabbat services we had when I went to school at the Jewish Community Center growing up and the small group of Jewish kids I went to school with — the special bond we had.

I remember having friends over for Hanukkah and Passover dinners and getting to expose them to my culture.

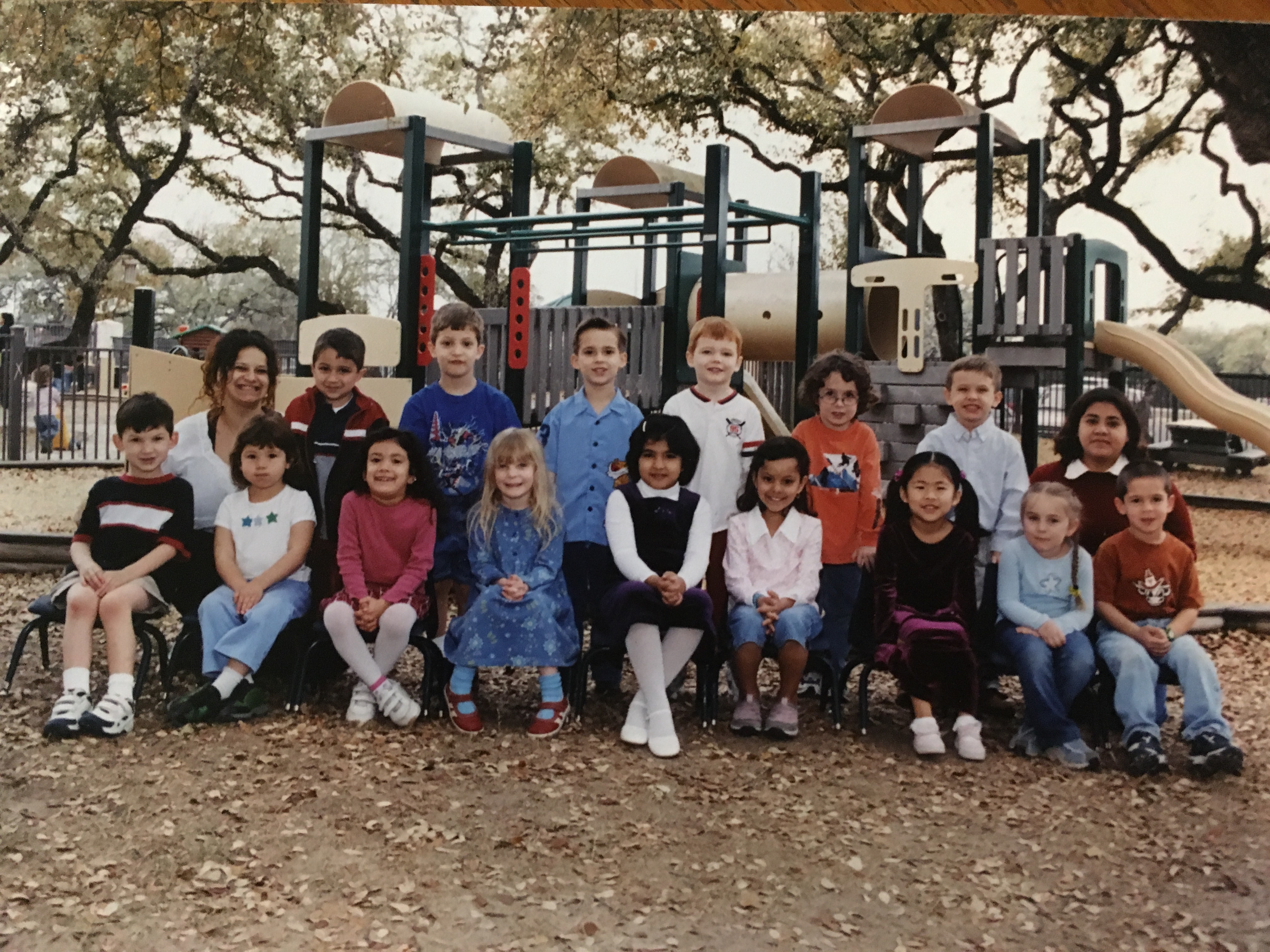

Throughout elementary school, I never fully realized how my religion could be such an issue.

Even when classmates said anti-Semitic things, it never fully registered in my mind it was bad. I was just used to it.

My mom used to come to my classes around Hanukkah — which is normally around the same time as Christmas — every year and teach about Jewish history. We would light a menorah and play with dreidels and eat chocolate coins called Hanukkah gelt.

I always thought it was just something fun my mom decided to do and never realized it was to protect me and my Jewish classmates by educating our peers.

By the time I was in middle and high school, I was numb to any anti-Semitic jokes or comments. I thought it was just a normal thing everyone dealt with.

Some of my classmates denied being Jewish to escape ridicule, and I still never fully understood because I knew I was OK, and I could get away with just ignoring it.

It wasn’t until coming to BYU and being one of six Jewish students on a campus with 33,000 students that I felt like an outsider.

During new student orientation, I remember a girl seeing the Star of David I was wearing around my neck and asking me if there were a lot of Jews in America. I explained to her that there were, especially because of World War II. She said she didn’t know that much about history.

Questions about my necklace came constantly throughout my first semester at BYU. Eventually, I stopped wearing it so I could feel normal.

I was a shy, lonely 17-year-old, and I just wanted to be normal. So, I started to investigate The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

I felt out of place because I felt like a bad person for not being more religious and not knowing more about my religion, so I sought that through a different religion.

I quickly realized that, while I love the members of the Church, it wasn’t for me.

Unfortunately, once you start to investigate, it’s hard to turn around and say you’re not interested.

I still get missionary calls and emails from friends asking me how I’m doing with the Church.

It’s OK.

I’ve learned so much at BYU — and especially through being a minority at BYU — and it has enabled me to help so many others.

I have also learned to be more tolerant.

Anti-Semitism is still an issue in the United States, and it’s very present at BYU. Not through people being intentionally offensive, but through a general ignorance when it comes to what is and is not OK to ask.

I’ve had friends tease me about being terrible with handling money because, stereotypically, Jewish people are supposed to be good at handling money. I have friends who have been asked if their parents are bankers. I’ve been scrutinized for wearing my Star of David during dance performances. And I’ve had friends who have been asked if they realize our religion is incomplete.

Being Jewish has always been uncomfortable, but for me, it’s especially scary after recent events.

During summer 2018, the cemetery where my grandparents are buried was vandalized with swastikas and anti-Semitic slurs.

This was the first blatantly anti-Semitic incident I had been aware of occurring for a while, and the number of instances have only increased since.

The shooting in Pittsburgh on Oct. 27 is what finally made me realize I am not safe.

A shooting could happen at any synagogue across the United States — including the synagogue I attend in Salt Lake City and any of the synagogues my family attends.

Growing up Jewish was scary. Being Jewish is scary. And it will continue to be scary.

What helps is to have people around us who support and protect us.