See also “Utah works to improve indigent public defense“

Correction, 7/25/18: A graphic in this story has been corrected to show the caseload number previously marked as representative of Utah County is actually a statewide figure.

Across the nation, public defense systems are struggling in a tangle of extreme workloads, insufficient funding and unreasonable trial wait times. For Louisiana, Missouri and New York, enough is enough. Public defense advocates are suing their states for more funding, and many public defenders are refusing to take on new cases.

According to guideline six in the American Bar Association’s “Eight Guidelines of Public Defense Related To Excessive Workloads,” public defenders may file motions asking a court to stop the assignment of new cases or withdraw from current cases when workloads are excessive and other adequate alternatives are unavailable.

Indigent public defense in Louisiana has been especially deplorable, and 15 of the state’s 42 defender districts have been forced to take action, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

The U.S. Department of Justice says Louisiana is the only state that pays for its indigent defense system primarily through speeding tickets and other locally generated revenue instead of guaranteeing funds through the budgeting process. As a result, Louisiana has the highest incarceration rate in the country and a public defense system on the brink of collapse.

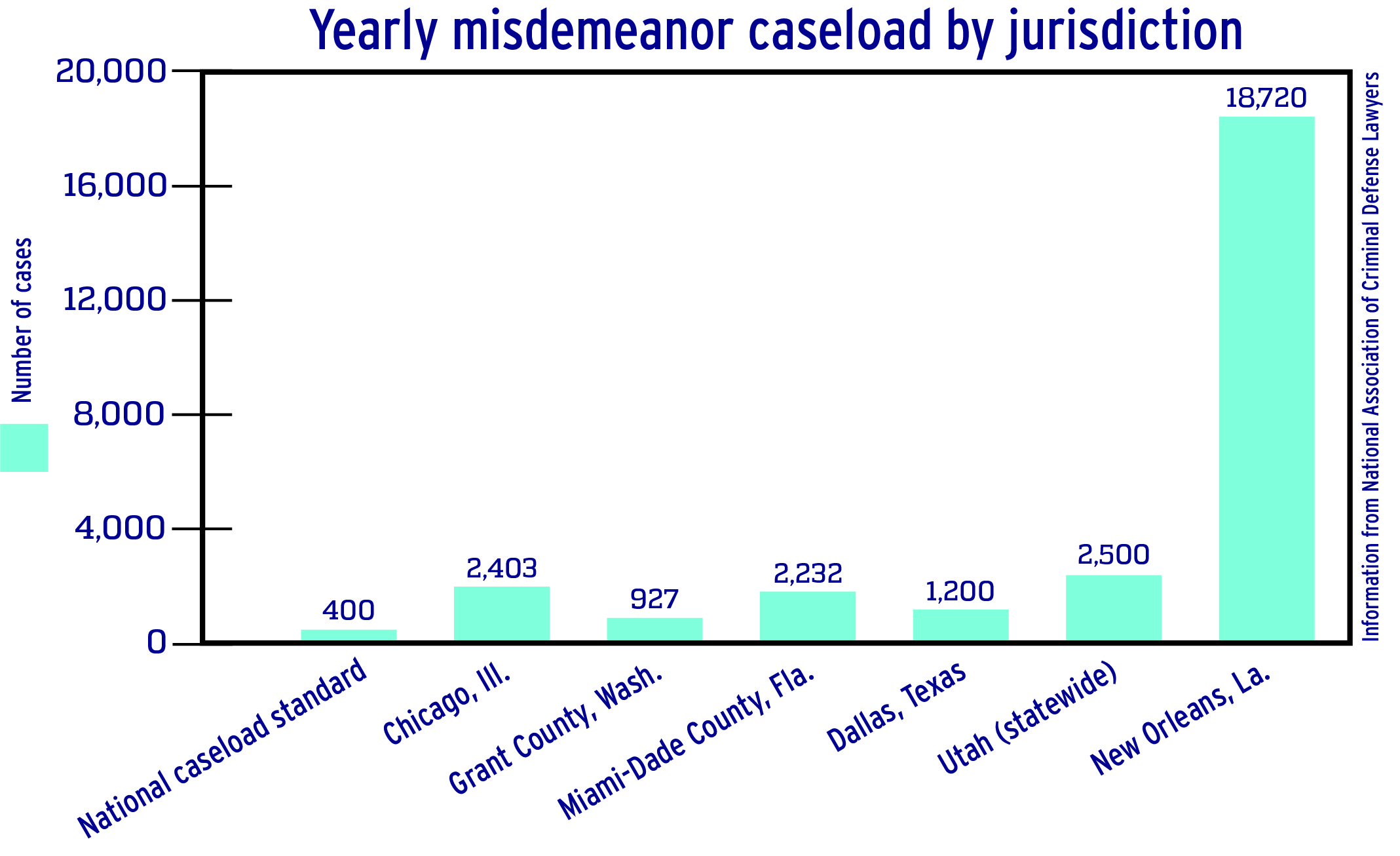

The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers claims that, in New Orleans, part-time defenders are handling the equivalent of almost 19,000 cases per year per attorney, which limits them to seven minutes per case.

Kris Tina Carlston, who received her J.D. from the J. Reuben Clark Law School and now directs BYU’s Pre Professional Advisement Center, does not believe seven minutes is enough time to go through all the repercussions of what happens if a client takes a plea deal or pleads guilty.

“One of the saddest things is when people are told to plead guilty to get out of it, and then they fail to recognize they no longer qualify for things like food assistance programs,” Carlston said.

According to The Guardian, the 16th Judicial District in Louisiana convicts and sentences up to 50 indigent defendants at once for major felonies that carry up to decades in prison. Subsequently, the single public defender who represents them all struggles to present any of the facts and arguments in their separate cases.

The American Civil Liberties Union and the ACLU of Louisiana filed a class-action lawsuit against the New Orleans Public Defender Office and the Louisiana Public Defender Board for failing to abide by defendants’ Sixth Amendment right to legal representation.

Missouri’s 370 public defenders handle more than 80,000 criminal cases a year for indigent clients — an average of 216 cases per attorney, KCUR reported.

In a study of the Missouri Public Defender System and attorney workload standards, the American Bar Association concluded that the state should have nearly twice as many lawyers to meet the standards set for the minimal time needed to adequately represent clients.

In 2017, the American Civil Liberties Union announced it was filing a class-action lawsuit against the state of Missouri over the unconstitutional system of public defense with the ACLU of Missouri, the Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center at St. Louis and Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe.

“We’ve been jumping up and down trying to call attention to this matter for the last two years, telling the state, ‘this is coming, this is coming,’ although we didn’t know precisely when it would come,” Michael Barrett, the director of the Missouri State Public Defender Office, told The Atlantic. “It was inevitable, just given all the studies that have been done regarding our caseload and the limited number of lawyers the state gives us.”

New York’s Chief Public Defender William Leahy told Stateline the public defense system has been a national failure.

In a statewide study in 2006, New York’s county-funded public defense system was found to be “severely dysfunctional”; however, New York may actually be a success story.

According to The New York Times, a seven-year-long class-action lawsuit was brought by the New York Civil Liberties Union and the law firm Schulte Roth & Zabel. New York settled the lawsuit and began funding a statewide public defense system that will be fully-phased in by 2023 at a projected annual cost of $250 million.

“What is portrayed in the movies and television isn’t what’s really happening,” Carlston said. “People are not being treated equally, their voices are being silenced and perhaps suing will encourage news outlets to publicize the issue more and hopefully result in increased funding.”