Emma, not her real name, was 14 when her years of physical and emotional torment began.

They were three athletic, enthusiastic and popular 15- and 16-year-old boys in a small Idaho high school. She was a shy, under-confident 14-year-old girl who had skipped a grade that year and didn’t have many friends.

The boys were in gym class to fulfill a general education requirement. She was in gym class to get out of a drama class that required her to view materials that went against her values as a member of the LDS Church.

The boys were known for pulling up girls’ shirts and groping them below their waists.

Emma would’ve done anything to help someone else, she recalled a church leader saying about her. And according to Emma, that’s exactly why the boys targeted her.

One morning, about a week into winter semester, Emma was sent into the supply room to retrieve class materials. There they were — those three popular boys — waiting, she thought, to help her carry things back to class.

“So I went over to a cabinet, and then I heard, ‘Don’t move,'” Emma, now a 20-year-old junior at Brigham Young University, recalled. “And then I turn(ed) around, and they (had) a knife to my throat. … They said, ‘We’re going to do this to you. And you’re not going to tell a soul, or we’re going to kill you and kill your sister.'”

They told her to strip and lie down. More in fear for her sister’s life than her own — one of the boys was in her LDS ward and knew where her family lived — she did as they said.

They sexually assaulted her every other school day for the next four months.

“I was so confused,” Emma said. “This was my Young Women leader’s son and his friends. Why were they doing this?”

The abuse finally stopped when Emma’s father walked in on her crying one day. Though she didn’t fully disclose to her parents at that time — she only said some boys at school had pulled her shirt up — the investigation that followed yielded complaints from enough students that girls were no longer sent to the supply room, and boys and girls were separated in gym class.

By keeping her sexual “harassment” complaint generic, Emma’s attackers were never able to trace it back to her, which she felt kept her sister safe while stopping the regular abuse. The school contacted police about a number of groping complaints against the boys, but they only ever received a warning. Emma said at least one of her attackers would later serve a full-time LDS mission.

Emma would spend the next four and a half years keeping the painful and difficult emotions of those repeated sexual assaults to herself, all while continuing to have classes with, attend school activities with and eventually graduate with her rapists. She would experience anxiety, depression and even suicidal thoughts. She would not fully disclose her experience until her freshman year of college, and she would later require surgery for damage done during the repeated assaults.

Emma also said she struggled with how attendance at her own church made her feel unclean. “We (victims) are viewed as liars and people who are impure and dirty and needing to repent even though we did nothing wrong,” she said.

A muddle of metaphors

The problem, according to marriage and family studies professor Jason Carroll, is not in the church itself, but in how people are misunderstanding and applying its doctrines.

“I think there’s a recognition of the realities of sexual assault,” Carroll said. “That doesn’t mean we don’t have some unintended lack of awareness or ways that we don’t address problems perfectly or correctly.”

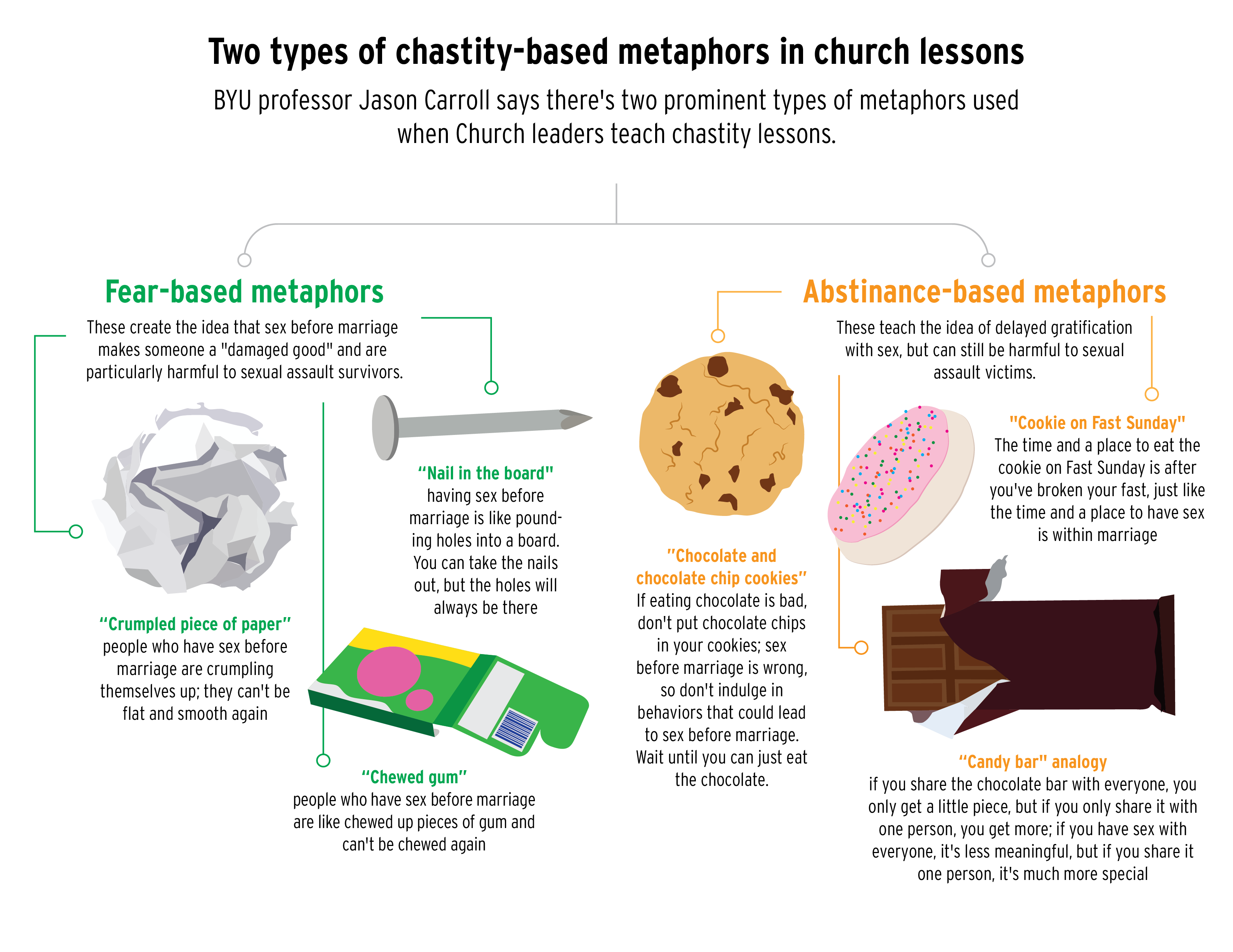

Carroll said he’s fascinated by how many young people have told him how leaders taught them through metaphors or object lessons about avoiding pre-marital sex. He explained two kinds of metaphors: the first are “fear-based” metaphors, such as the “bubble gum analogy,” which compares people who have sex before marriage to chewed pieces of gum.

These messages are particularly devastating to sexual assault survivors, Carroll said, because they create a “damaged goods” message and don’t provide resources or hope to help victims know they can recover.

The other kind of metaphors, he said, are abstinence-based metaphors. These teach a delayed gratification pattern, such as not eating chocolate chip cookies on Fast Sunday. While they’re less damaging than fear-based metaphors, Carroll said one of the biggest problems they create is the idea that chastity is behavioral.

However, “(Chastity) is fundamentally something that no one can take from you,” he said.

Despite increasing awareness of the harm these metaphors cause, Carroll said church leaders continue to use them because they haven’t yet learned how to talk directly about sexuality.

The best metaphor, Carroll said, is no metaphor. He added that if church leaders and members addressed chastity in healthier ways, there would be a better platform to help abuse and assault survivors.

Lack of resources?

Anna, not her real name, still can’t stand the scent of eucalyptus.

The 21-year-old BYU senior was orally raped by a man she met through a friend two summers ago. She now associates the scent of eucalyptus, which came from a body lotion, with her assault.

“There are still little things where it’s really traumatic,” Anna said.

The healing process would be easier if there were more resources within the church for sexual assault victims, with an emphasis on the healing power of the Atonement, according to Anna.

“I think that that’s a very big thing we could change: … changing the way we talk about sex so that it doesn’t feel so damaging when somebody takes that from you forcibly, and then providing resources,” she said.

Emma said there’s a lack of resources for those teaching chastity lessons.

“I felt completely horrible and dirty and wretched and used (after chastity lessons),” Emma said. “And it’s just because people don’t know how to teach them.”

A search on lds.org showed that the church has published several talks and other articles since 2016 addressing the realities of sexual assault, as well as how to best support survivors. One was the Gospel Topics entry for abuse, which compiled scriptures, talks and other sources listing what church leaders have said about abuse. In addition, a 2017 Ensign article titled “A Bridge to Hope and Healing,” written by LDS Family Services employee Nanon Talley, explored how victims can be understood and helped.

There is also a 2001 Ensign article titled “Healing the Spiritual Wounds of Sexual Abuse” and an April 1992 General Conference talk by Elder Richard G. Scott titled “Healing the Tragic Scars of Abuse.” Elder Scott gave another General Conference talk in April 2008 titled “To Heal the Shattering Consequences of Abuse.”

The most prominent resource appears to be the Ministering Resources link, which is available through the LDS Family Services website. It contains training for church leaders on issues such as abuse, addiction and mental health. The resources on this website are available only to ward and stake council members.

In addition, the chastity lessons for young men and young women found on lds.org are largely the same lesson outline including videos, talks for references and questions for discussion.

Healing through awareness

The biggest thing that will change how people think about sexual assault, Jaylene Mangum said, is talking about it.

Mangum is the former Rape Crisis Coordinator at the Center for Women and Children in Crisis in Orem. Her job responsibilities included leading a team of volunteers that responded to victims after they had been assaulted and teaching a once-a-week class for sexual assault victims.

In her experience, people of all demographics buy into preconceptions about sexual assault victims.

“‘What were you wearing? How were you acting? Why were you there?’ When you ask them those questions, it automatically puts the blame on the victims when they already blame themselves so much,” she said.

Those preconceptions provide a false sense of security, according to Mangum. For example, some people believe rape only happens if a person is walking down a dark alley alone at night, so they feel safe knowing they can choose to avoid that situation. However, Mangum said the vast majority of victims are assaulted by someone they know.

The reality of this can be seen in BYU’s recent campus climate survey on sexual assault. In all, 12,739 BYU students responded to a survey asking if they had experienced unwanted sexual contact in the previous 12 months while they were enrolled at and attending BYU. One result of the survey showed that, of the 475 students who provided information on 730 incidents of unwanted sexual contact, the perpetrator was a former or current dating partner or spouse in 52 percent of the incidents. In 12 percent of the incidents, the perpetrator was a current or former friend or roommate. Only six percent of incidents involved a stranger as the perpetrator.

Another issue the report highlighted is how under-reported sexual assaults remain. Of the 730 incidents reported in the survey, only three percent of the incidents were reported to local police and only one percent was reported to BYU police. While a small percentage of respondents said they reported to people like bishops or a counselor, 64 percent of the cases were categorized as “None of the above” when asked who they reported the assault to.

In Emma’s case, she fully disclosed her story to her family in December 2015 — about four and a half years after the regular assaults stopped. They initially doubted her story, and she sought counseling for anxiety and post traumatic stress disorder.

Emma did not take any kind of action against her attackers until BYU’s Fall 2017 semester, when she worked with the school’s Title IX Office and with detectives in her Idaho hometown to open a civil case against the three boys who assaulted her in high school. It’s not a criminal case — Emma said there’s not enough evidence for that — and it’s not a lawsuit, but it means Emma is notified if any of her attackers are coming to campus, such as if they buy tickets to an event. It also means if more information ever comes out, she can move forward with a potential lawsuit. Emma said the case is currently closed, and she intends to keep it that way — though she could re-open it at any time.

Emma also worked with her student ward bishop and her home ward bishop in October 2017 to add flags to the boys’ church records.

“The flag is used solely by bishops and can only be seen by current bishops to mark a person’s records so that a future bishop can have information needed to keep their ward safe and functioning,” Emma said. “In the case of these boys, their records were flagged that they have a serious sexual sin that they have not repented of or come forward with, in the hopes that a future bishop would be able to keep his ward safe by not, hopefully, extending callings to do with the youth, children or women.”

Emma said neither bishop had called a sexual abuse hotline upon her disclosure because police had already been involved and the civil case was already closed. With Emma’s permission, her student ward bishop also followed up with BYU police about her case.

Though Emma recognizes she may receive criticism for not taking action against her abusers sooner, she said taking action is not always as simple as it seems, and she encourages people to refrain from judging victims for what may be perceived as a lack of action. Both she and Anna said victims should remember it’s not their fault they’ve been abused.

“No matter what you were doing or how you reacted, a lack of consent is fundamentally sexual assault,” Anna said.

Mangum said she is a firm believer in healing.

Resources in the Provo area for sexual assault victims include:

Center for Women and Children in Crisis — Sexual Assault Crisis and Information Hotline: 801-356-2511

Utah Domestic Violence Link Line — Open 24/7, seven days a week, 1-800-897-LINK (5465)

Rape & Sexual Assault Crisis Line — Open 24/7, seven days a week, 1-888-421-1100