Editor’s note: Immigration has been a political boondoggle for at least two decades in the United States. Congress has yet to come up with a system that will successfully address the complexities, and President Donald Trump has taken some decisions into his own hands.

See also “LDS Church’s stance on immigration”

Last in a series.

TUCSON — A church with a unique mission is just another part of downtown Tucson at first glance.

Music and laughter float to the church from nearby restaurants; people stroll through the warm early-evening air. In Tucson, as in many places, Friday night hums with weekend energy.

In some ways, however, the church is worlds away from its carefree surroundings.

This church is home to the Inn Project, where immigrants with children come for food, rest and other relief after being processed by ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) and approved to pursue asylum.

The Rev. Dr. Dottie Escobedo-Frank, who chairs the Inn Project board, said the project is named for the Bible story where there was no room for Mary and Joseph at the inn. It began in December 2016 when ICE asked local Methodist churches for help getting children out of detention centers that Escobedo-Frank said are referred to by immigrants as “helado,” Spanish for “the freezer.”

It’s an unusual arrangement — Methodist churches helping immigrants by working directly with ICE, an organization Escobedo-Frank said they otherwise disagree with — but one that, as of July 2017, has provided 5,000 meals, registered 250 volunteers, logged over 4,500 volunteer hours at a $100,000 value and reunited over 1,000 immigrants with family members all over the U.S., according to the Desert Southwest Conference website. (A conference is a regional area in the Methodist church that may cover part of a state up to parts of several states, according to the United Methodist Church website.) As of December 2017, they have served 2,267 individuals and 678 families.

Another similar facility in Tucson is Casa Alitas, run through Catholic Community Services, and Escobedo-Frank said similar operations run in Texas through other denominations.

Children first

Since children are the Inn Project’s primary concern, Escobedo-Frank said their housing criteria is single parents or one parent with children under 18. The children are often traveling with one parent, with the other parent meeting them in the U.S. later.

Escobedo-Frank said these are asylum-seeking immigrants who turn themselves over to ICE after “journeys that are just incredibly long and difficult” and can last anywhere from three days to three weeks. Having been processed and granted the opportunity to seek asylum by ICE, and with future court hearing dates set, they are technically documented immigrants.

For the children’s safety and to maintain good relations with ICE, Escobedo-Frank said they’re careful not to house anyone who doesn’t come directly from ICE.

Wearing ankle monitors, families meeting the criteria are transported by ICE from the detention center to the Inn Project, where they can eat, shower, get new clothes, rest and play. They don’t often stay more than a day, however, as it’s from the Inn Project that they make arrangements to meet family elsewhere in the United States or otherwise move on.

Escobedo-Frank said the Inn Project does not know what happens to immigrants after they leave their facilities.

She also said previously, ICE officials would just drop immigrants off at bus stations where they would “camp out” for 24 hours. In addition, the Desert Southwest Conference website states that when ICE initially asked for help in 2016, their officials expressed “the desire not to place parents with children in detention centers or merely drop them off at bus stations and Walmart parking lots to fend for themselves,” as immigrants sometimes became stuck for days.

Taking care of each other

Daily Universe reporters visited the Inn Project in March, interacting with immigrants and volunteers.

The Inn Project is tucked away in the church’s basement. An inconspicuous set of stairs on the far-left side of the sprawling, stucco complex leads down to a standard-sized door, which opens into a retrofitted living area that Escobedo-Frank said can house a maximum of 50, though fitting that many is difficult.

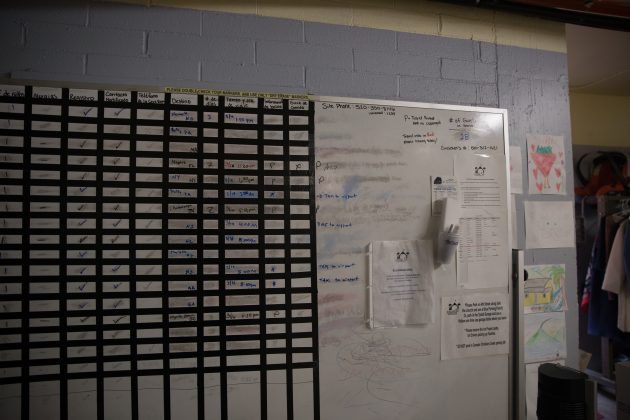

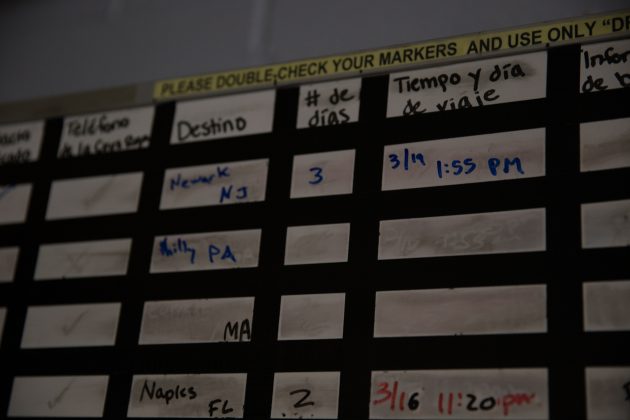

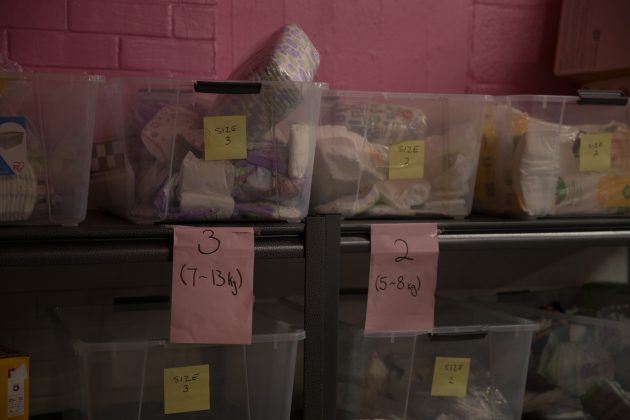

There were 38 immigrants from Brazil or Guatemala during the Daily Universe’s visit. South American and U.S. maps near the door help immigrants show Inn Project volunteers where they came from and where they’re going. A carefully organized whiteboard shows various details about each immigrant, such as their names, destinations and travel days and times. Racks of clothing sit near the door, where immigrants can choose new clothing, particularly cold-weather clothes they’ve never needed before.

Escobedo-Frank said many people think the Inn Project receives mostly Mexican immigrants, but that’s the second largest group, with the most immigrants coming from Central America, particularly Guatemala.

She said many immigrants go to the east coast, though immigrants go all over the U.S. The immigrants Daily Universe reporters met were largely headed for southeast cities.

On one side of the room is a wide kitchen, with a doorway leading to showers and bathrooms beyond the kitchen. The main floor is covered by multicolored cots and blankets. Immigrants of all ages lounged or talked quietly, sometimes sending shy glances and smiles at the reporters.

Escobedo-Frank said immigrants often hold each other’s babies so parents can sleep, and they help with cooking and cleaning. “They take care of each other a lot,” she said.

Past the cots, a doorway on the main room’s opposite side leads into a well-furnished playroom. Children laughed and ran through the ample toys, or smiled at cartoons playing in Spanish on a wide-screen TV as if they had no idea how far they had come or what their families had been through.

A small immigrant boy, perhaps only a year old, toddled toward reporters from the playroom, the innocence in his face belying his circumstances. He threw his arms around a reporter’s legs and looked up with a bright smile.

Past the bathroom and shower facilities, a staircase leads to the church’s sanctuary. The wood pews, stone floor and multicolored stained-glass windows lend reverence to the room’s imposing silence. It’s here immigrants sometimes “talk to God,” Escobedo-Frank said. “They do often come up here and just sit in the quiet and pray and get some time to relax.”

Escobedo-Frank said the immigrants aren’t with them long enough for the Inn Project to offer any social services, but both she and Associate Pastor Jamie Booth were social workers before becoming pastors.

She also said if there’s an immediate need, the Inn Project works with non-profit Justice For Our Neighbors, which “provides free or low-cost immigration services for low-income immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers,” according to its website.

Booth said she can’t think of having a bad day when she’s at the Inn Project, recalling a man who said, “God bless America” and “God bless this church,” when he saw her bringing groceries in.

“People are happy, and they’ve been through so much more than I have,” she said. “People are grateful just for what’s here.”

The Inn Project has received about $160,000 in grants and donations as of July 2017, according to the Desert Southwest Conference website. ICE does not help with any of the Inn Project’s costs; however, anyone can donate online. The Inn Project could also expand into a second church if needed.

Still, Escobedo-Frank hopes for a day when the Inn Project won’t be needed at all. “I hope (the Inn Project) goes away,” she said. “I hope it’s never needed again.”

Check out reporter Kaitlyn Bancroft’s personal reflections from the trip.