Editor’s note: this story pairs with “BYU-Hawaii student led tourists to safety during false missile alert panic”

An alert that a ballistic missile was headed for Hawaii sent the Aloha State into a panic on the morning of Jan. 13, 2018 — a mistake that took the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency a painstaking 38 minutes to correct.

Recent talk of North Korea’s success with missile technology and overall tension between North Korea and the U.S. gave Hawaiians good reason to believe what their state was telling them. But there was no real missile threat to Hawaii.

This event has raised concerns about the effectiveness of state emergency alert systems. After all, Hawaii’s slip-up isn’t the only recent false alarm incident. At the beginning of February, a false tsunami warning went out to people living along the East Coast, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean.

“There’s a failure in sending the wrong message,” said Joe Dougherty, Public Information Officer for the Utah Division of Emergency Management. “When Hawaii sent that message, they sent their whole state into a panic. That’s a huge, glaring failure to scare everybody.”

Since the incident in Hawaii, Dougherty said he has been working to reassure Utahns that what happened there is “very, very extremely unlikely to happen in Utah.” He said the division can address everything that went wrong in Hawaii.

A report by the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency indicated that State Warning Point employees were beginning to conduct a ballistic missile alert drill the morning of Jan. 13, but that one employee, who was later fired, “erroneously activated the real-world Alert Code.”

Later the employee claimed he heard the exercise was not a drill, though the state report said employees were clearly told it was an exercise.

The report ultimately concluded that “insufficient management controls, poor computer software design and human factors” contributed to the mistake.

Dougherty explained why a similar situation could be prevented in Utah, which has different alert processes and software than Hawaii.

Utah’s messages are pre-scripted and stored outside the state’s alert system. They must be typed into the system in order to be sent. In drills, Utah’s Emergency Management employees use clear communication to help everyone understand the drill is not a real emergency situation. They plan to verify outgoing messages with repeat-back communication. Before sending a message, a window on the computer asks the employee “Are you sure?” to further vet any false alerts.

Dougherty also said there are really only six people in the state who can issue a message for an alert, including the governor, lieutenant governor and commissioner of public safety.

“If it comes from anybody else, I’m not doing it,” he said. “So that’s one of our safety nets.”

Dougherty explained that the state of Utah uses a system that the Federal Emergency Management Agency created, called the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System.

Through the warning system, the state can send alerts to televisions, cell phones, message boards on the freeway, social media, sirens, weather radios and other devices.

Dougherty said the Division of Emergency Management has run tests and evaluated its systems for shortcomings since the Hawaii incident. He added that it’s important to remember the government takes its role in preparedness seriously.

“Generally the government is made up of a lot of people who really care about doing the best possible job and want to make sure that people are safe,” he said.

Possibility of a missile attack in Utah

Utah isn’t as close to North Korea as states like California, which has, as of September 2017, been actively preparing for a ballistic missile threat, according to Newsweek.

However, David Wright, co-director of the Union of Concerned Scientists Global Security Program and nationally recognized nuclear weapons policy expert, said North Korea has been successful at developing intercontinental ballistic missile technology and increasing the range of those missiles.

From 1990 to the present, North Korea has increased its missiles’ range from 745 miles to over 8,000 miles, according to The New York Times.

Utah is well within North Korea’s 8,000 mile range — Salt Lake City is approximately 5,800 miles from Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea.

“In principle, every part of the U.S. is at risk,” Wright said.

Launching a missile isn’t as easy as pushing a button, though. Wright said factors like electronics, missile guidance systems and re-entry heat’s effect on a missile’s warhead would influence a missile’s performance.

Missile accuracy isn’t perfect, either. Wright said a long-range missile — like the ones that could reach the U.S. — would probably land within 6.2 to 12.4 miles of its target. This makes large population centers like California better targets than small military sites.

But Wright isn’t losing sleep over the possibility of an out-of-the-blue missile attack.

“I think the North Korean leaders have shown that they’re not suicidal,” he said. “And they know that attacking the U.S. or one of its allies would be suicidal.”

Instead, Wright said the U.S. should be striving to reduce the tension between it and North Korea, since tension is what could lead to a missile launch based on bad information, assumptions or a fast-moving, misunderstood situation.

Dougherty said while a threat from North Korea is something the state Division of Emergency Management considers, it is viewed as less likely than other disasters.

“The thing that we talk about the most, that would be the most devastating and actually has a chance of happening, would be a 7.0 earthquake in the middle of winter that strikes the Wasatch Front,” Dougherty said.

Provo’s warning system

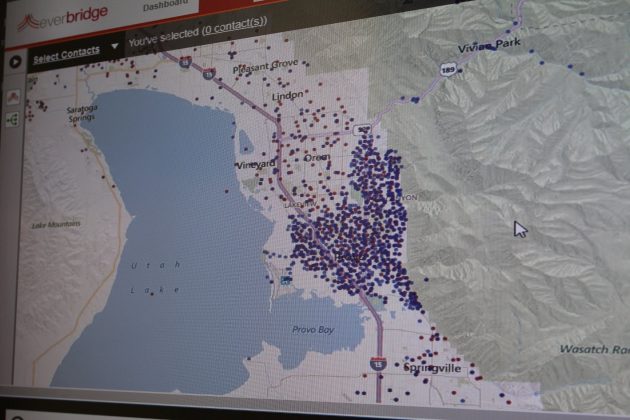

At the local level, Provo City is also part of a countywide, subscription-based emergency alert system. Residents can register for the system and choose to receive alerts about specific cities in Utah County and opt to get community information, as well.

Provo is also connected to the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System.

Specific criteria must be met before an alert is sent out, Provo City Emergency Manager Chris Blinzinger said.

“We experienced those types of incidents where there was some messaging sent out inaccurately or to a larger group than they were intended for,” Blinzinger said. “That helped us rein in the problem, do some more training and understand how to do this.”

He also said although Provo has evaluated its system in a non-emergency situation, that doesn’t mean the system is foolproof.

While the state is focused on the threat of an earthquake, Blinzinger said, Provo has narrower focuses specific to the city. These include scenarios like wildfires in this year’s coming dry season and hazardous material spills.

Blinzinger said it is best if college students in the community take responsibility for their own safety instead of relying on others like parents to do it for them.

Provo residents can take responsibility for their own safety by registering for local emergency alerts, stocking up on a realistic supply of food and water, learning families’ phone numbers in case of cell phone failure and getting to know neighbors.

BYU students can also sign up for BYU’s Y-Alert system that sends messages through email, phone call and text messages.