Editor’s note: This story pairs with “Timeline: A History of DPRK-U.S. Relations”

President Donald Trump threatened to “totally destroy” North Korea on Sept. 19 in his first address to the United Nations General Assembly, and he has continued to berate and threaten the nation and its leader.

Japan’s defense minister Itsunori Odonera stated on Oct. 23 that North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile capabilities have escalated to “unprecedented, critical and imminent” levels.

Ri Yong Pil, a senior North Korean official, warned on Oct. 26 that the international community should seriously consider the threat that North Korea could soon test a nuclear weapon above ground.

And in recent weeks, major U.S. media have reported that North Korea has tested an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of hitting the White House.

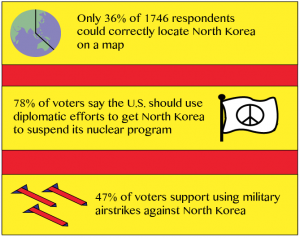

All of these escalations, both on the part of the U.S. and North Korea, have occurred in the last year alone. However, despite this alarming acceleration in rhetoric, the New York Times found in July that of 1746 Americans surveyed, only 36 percent were able to actually locate North Korea on a map.

Furthermore, respondents who were able to locate North Korea were far more likely to favor non-military solutions for addressing conflict with the DPRK. These findings suggest a relationship between empathy and education.

“The knowledge and information you get about a place or people shapes the way you think about what acceptable options are,” said BYU history professor Kirk Larsen. “If (people) are more likely to know a bit about North Korea, they are more likely to think about them as real people rather than this cartoon threat.”

North Korea and the U.S. have had an antagonistic relationship, but accompanying this relationship is the perception that North Korea and its people are inherently illogical.

“There is this perception that North Koreans are irrational or crazy. And I think that 70 years of North Korea’s existence proves the contrary,” Larsen said.

Larsen pointed out that North Korea has definitely been behind proactive acts, everything from killing two American soldiers on the DMZ in 1975 to possibly sinking the Cheonan, a South Korean military vessel, in 2010. However, Larsen said the nation is rational and realizes that there are certain lines that it cannot cross.

Equally misunderstood may be the fact that the North Korean people do not live with the same values or way of thinking as many Western countries.

In South Korea, it is seen as a right of passage for students to protest and demonstrate against the government, according to BYU linguistics professor Clay Parker.

But at the end of the day, those students are able to return to their homes and resume their normal lives. The same behavior would earn a North Korean citizen a one-way trip to a gulag.

However, even more than a difference in free-speech enforcement, North Koreans simply have a different way of viewing the world.

“North Koreans have this kind of agrarian, nature-is-cruel type of attitude,” said Parker. “We think, ‘why don’t they do something about it?’ They’re not even thinking about that. They are thinking, ‘I just want to get by, I just want to survive.’ When we apply our Western values and world view to them, we skew our understanding of the North. The people don’t have experience with democracy, so they don’t miss it.”

Applying Western or Eurocentric values to the distinct cultures across Asia and the rest of the world can lead to a fundamental misunderstanding of the way in which many people live. However, this misunderstanding is ingrained in Western culture and has been for hundreds of years.

In his text “Orientalism,” author Edward Said makes the argument that European scholars, writers and historians have long tried to analyze the Asian world through a Eurocentric lens. However, doing so only rationalized beliefs that “Europeans (were) superior to other peoples and affirmed the European right to rule and ‘civilize.’”

The alternative to either ignorance or cultural imperialism is becoming informed about the cultures and values of nations around the world. In the case of North Korea, this means learning about the experiences and indoctrination that have shaped the lives of 25 million people.

Parker recommended reading texts that describe life in North Korea, but added a caveat: there is an issue with reading books that come exclusively from defectors.

“The problem with relying on books from defectors, is that they have a bias,” Parker said.

“(Life in the North) is not all bad. It’s like learning about Mormons through reading anti-Mormon literature.”

Parker instead recommended texts like “The Real North Korea: Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia,” a book by Russian author Andrei Lankov that provides a non-western scholar’s interpretation of life in North Korea.

Parker also mentioned news outlets like NK News who have staff across the world that are focused on providing timely and accurate news about the North. NK News also offers a reoccurring feature that allows readers to ask questions about everyday life and politics in North Korea and receive answers from actual citizens of the DPRK. Access to these features does require a subscription, but they are free to view through the BYU Library.