Feb. 14, 2016

SALEM, Utah County – Everything is quiet in the Fifitas’ family room except the deep, calm voice of Richard Fifita praying — and the snickers, giggles and grunts popping up as other family members anticipate dinner.

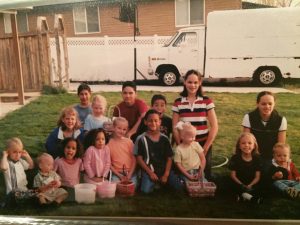

As soon as the “amens” signal the prayer’s end, a horde of children run to the kitchen for a Valentine’s Day dinner. The adults just as quickly set up three rectangular tables in order to seat all 13 Fifita children, (ages 5 to 30), a few in-laws, Richard and his wife Linda, and eight grandchildren.

It’s a family rich in diversity — something Linda couldn’t have anticipated as a young girl who wanted more than anything to be a mother. But the ritual is a joyful one: it’s the last time she expects to have all their children together for a long time.

Four of her children are biological; the other nine are adopted. Linda describes the family’s adoption journey as miracle-filled. It has shown them the blessings of a mixed-race family by teaching them to be empathetic and committed to their children, especially during difficult times.

One trial for many adoptive families is understanding children who have not only endured traumatic backgrounds and the uncertainty of adoption, but who don’t have the same physical appearance as their adopted parents.

Spring 1984, Provo

The day is bright, but Linda leaves her pre-marital doctor appointment feeling heavy. The only profession she’d ever wanted was that of a mother, a dream that now seemed to be crushed.

She heads home to call her fiancé, Richard, and tells him they need to talk. They decide to meet at his apartment, east of BYU. As she enters, she blurts out the news: “I can’t have children.”

Linda follows the news with a way out: Richard should find someone else to marry if he wants a family.

But he asks her to get her patriarchal blessing so they can read them together. She does, and once she returns, they peruse the words. Two phrases stick out.

“Sons and daughters,” one says.

“Men and women,” the other says.

“That’s all I need to know,” Richard says.

February 1985, Utah

Eight months into their marriage, Linda starts to feel sick. Weeks pass. The illness only worsens, but pregnancy test after pregnancy test — all eight of them — shows she’s not pregnant.

Right before she is to enter exploratory surgery to diagnose the problem, the doctors decide to take one more test.

“We can’t believe it,” they say. “You’re going to have a baby.”

Years, trials and miracles later, the Fifitas have four biological children.

It wasn’t until a fifth pregnancy that ended in a miscarriage that Linda considered adoption. A dream showed her a child she knew she was supposed to have. But she couldn’t conceive.

“It was a huge turning point to have gone through that (miscarriage) and still have that feeling that something was missing,” Linda said.

Richard was happy with the children he’d been given. But he wanted to support Linda’s dreams. So he said, “Let’s do it. We’ll do it together.”

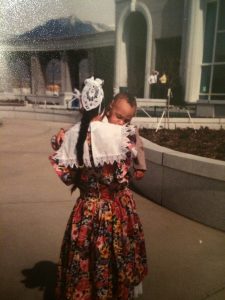

Linda knew from her dream that the child waiting for them was a black boy with a narrow face and curly hair. The baby they picked up in North Carolina was bald and round-faced.

“I hadn’t really had enough experience with how the Lord would speak with me to know that eventually that would be kind of a fulfilled prophecy,” Linda said.

She told her social worker he fulfilled her dreams. It wasn’t until after their family temple sealing that she realized just how much.

She sat him on a podium at the Orem J. C. Penney for a photo of him in his handmade tuxedo when she suddenly saw, exactly, her dream. “Because of that, I could start trusting the inspirations that came with future children,” Linda said.

Linda is white and Richard is Polynesian. Certain birth mothers looked for diversity and even certain races in adoptive parents, which often helped Linda and Richard. However, support groups taught Linda that all families have different stories and adoption is not a competition.

March 1998, Oahu, Hawaii

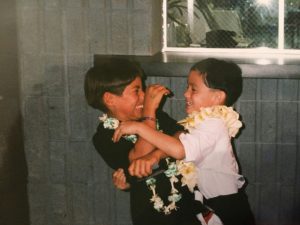

The Fifitas, including all four biological children and 2-year-old adopted son Ammon, get off the plane in Oahu. They take in the open, tropical airport surroundings. But their minds are on the boy they’ve come to pick up: 9-year-old Daniel.

The group leaves the gate and enters a corridor where they meet their social worker. She gives each family member a lei.

Six-year-old Joshua, though, sees only Daniel. He runs to Daniel, throws his arms around him and shouts, “You’re my big brother now!”

“Daniel was really receptive because the kids were there,” Linda said. “I think it made his adaptation to our family very good.”

Linda arranged for the family to pick up Daniel because she knew he wouldn’t feel comfortable surrounded only by adults — strangers.

The conversation on adoptive parenting, which takes place virtually through social media and physically through adoption support groups, shows that many parents have a similar mindset.

“Time and time again, you see how it’s not a competition,” Linda said. “It’s just a matter of doing what’s right to get your child where they need to be.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

September 1998, Orem, Utah

The cries of her newly adopted twin babies jar Linda awake. She drags herself out of bed without waking Richard. It’s 2 a.m. and he’s recovering from working two jobs and serving as a bishop.

Linda starts her routine, but as she burps Karina and feeds Kaelani, Karina throws up all over the three of them.

Linda cries out at no one in particular, but also anyone, “Someone help me!”

Miraculously, 8-year-old Melissa enters the room. “Mom, do you need my help?”

Relieved, Linda cleans up while Melissa soothes the twins.

“Mom, that was so fun,” Melissa says after. “You need to wake me up more often.”

All the adopted Fifita children came to them as babies except Daniel, who grew up in foster homes. The Fifitas said it was easier for the children adopted as babies to feel unified with their family and secure in their identities because that was all they knew.

But Linda said Daniel struggled at first, not trusting that his family was permanent. He was worried the family might abandon him, as others had.

Daniel also threw up at night as a child. After a while of cleaning sheets in frustration, Linda “realized this was his body’s way of reacting to so much stress he was going through,” she said. “And once I became more empathetic to it, it pretty much ceased.”

Feb. 14, 2016.

The older children at one end of the room discuss their brother Ammon’s missionary weight gain. At the other end a grandson, a younger white daughter and a half-black son jump off the couch onto a small bean bag yelling, “I would die for Riley!”

Linda and Richard agree with the “love is not enough” sentiment in adoptive parenting. Richard said love is always there, but parents need to work to develop it. “It’s like a fire, but you just have to keep putting the right wood and the right thing for the fire to just keep kindling,” Richard said.

Linda said there are times when it’s easy to love someone, and it’s great. “But there’s going to be times when you’re not going to like somebody,” she said. “That’s where commitment and dedication come in — and it’s really important to realize that it takes all of that. That love is a part of it, and love is part of the process.”