Nakai Salway was a senior in high school when his leg was amputated below the knee. Salway was born with a club foot, and his health issues have continued since then. He now uses a prosthetic leg or a scooter on the days his leg bothers him.

Eleven percent of U.S. college undergraduates in 2011–2012 reported having a disability. While disabilities can be difficult to accommodate, BYU is proud of its easily-accessible campus.

University spokeswoman Carri Jenkins described what BYU does to accommodate students.

“The majority of BYU personnel respond well and are supportive of and helpful to students with all types of disabilities,” Jenkins said.

Salway, a junior studying computer science at BYU, believes BYU does a good job providing necessary accommodations. With the addition of the Life Science Building, students with physical disabilities like Salway’s can more easily move around campus.

“Now if you are in a wheelchair or can’t use stairs, you don’t have to either brave that huge hill on the south side of campus or go all the way to the Tanner (Building),” Salway said. “BYU is accessible for people who might have trouble getting around.”

According to the Americans with Disabilities Act, an individual with a disability is “a person who has a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activity.” This definition includes people who have a record of the impairment, even if they are not currently suffering from the disability.

The Americans with Disabilities Act, which became law in 1990, “prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs, schools, transportation and all (places) that are open to the general public.”

BYU’s University Accessibility Center (UAC) works with students who need accommodations in order to attend school. Physical disabilities aren’t the only disabilities the UAC works with — the center has services for students with emotional, learning, physical, mental, chronic, visual, auditory and temporary disabilities.

“In a typical year, the UAC serves approximately 1,500 students who have chosen to use our services, and it is our passion and purpose to assist them in reaching their full potential,” Jenkins said. “We would encourage any student with a disability to visit the UAC.”

Devon Smith, a junior studying exercise science, was diagnosed with ADHD in high school. Smith was relieved to finally understand why he struggled to concentrate in the classroom. Since his diagnosis, Smith has looked for ways to help others who may be in the same situation.

Smith now represents the University Accessibility Center on BYU’s Student Advisory Council. The council collaborates with BYU students, faculty, administration and staff to improve the overall BYU student experience.

“Depending on your disability, there are many things the (UAC) offers. It’s not just for mental disabilities; it’s physical disabilities, emotional disabilities, things like that,” Smith said.

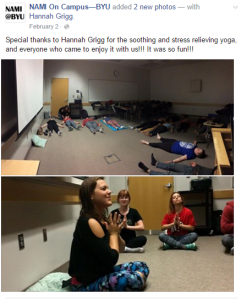

The UAC isn’t the only BYU organization that helps students with their disabilities. The BYU chapter of National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) aims to improve the lives of those affected by mental illnesses through educating and advocating.

Spencer Waters, a junior double majoring in neuroscience and psychology, is the co-president of BYU’s chapter of NAMI.

“We do anything we can to reduce the stigma surrounding mental health and get students the help that they need,” Waters said. “One of the most important things is education … Learn about the symptoms, learn about what a (mental illness is) and what it isn’t … Once you educate yourself on what mental health is to you, educate your friends.”

Ali Quintana, a 23-year-old junior studying accounting at BYU, was diagnosed with depression her senior year of high school.

“I have a great life, great friends, great family and I go to a great school,” Quintana said. “There’s never been a reason why I have (depression); it’s just something that I’m learning to live with and thrive with.”

Quintana wants to break the stigma associated with mental illnesses. She’s found strength in the people with whom she can have candid conversations about her depression, and she wants that kind of support to be available for everyone.

“I felt like there was something wrong with me for feeling this way,” Quintana said. “Sometimes, it’s perfectly OK to not be OK.”

Starting a conversation isn’t always enough to reduce the stigma that surrounds mental health issues. NAMI strives to educate students and the community on what mental health is and how they can support those who may have disabilities.

“It doesn’t make you any less of a person if this is what you’re struggling with. You shouldn’t be defined by your disease,” Waters said. “No matter what it is, it is manageable, it is treatable and it is real.”

Regardless of the different disabilities a student may have, the UAC offers different accommodations.

“School is hard enough already, so if someone is struggling with mental illness, it’s that much harder,” Quintana said. “But if (students) reach out, accommodations level the playing field and ensure that students have what’s necessary to succeed in their lives.”