Seth Bybee stands on the edge of a lake swarming with hippos and crocodiles in Rwanda, catching fireflies.

Bybee is creating phylogenetic trees, basically genealogy for fireflies, by collecting and studying fireflies from all over the world. He has been studying fireflies for three years and is leading researchers from BYU and the University of Utah in a study of the presence of fireflies in the state.

There are six species of fireflies known in Utah, and only two of them flash. However, only one of the two flashing fireflies has been documented and studied; the other is rumored to be in Utah.

Pyractomena dispersa, the known and studied firefly, is dark in color. The other species, photuris, comes in different colors but is primarily tan in Utah.

To get a better understanding of fireflies’ distribution in Utah, Bybee and his team partnered with the University of Utah and the Natural History Museum. Together, they have organized a website where people can report firefly sightings.

“We tapped into the collective intelligence of Utahns,” said Christy Bills, the invertebrate collections manager at the Natural History Museum.

Bills had collected data anecdotally for 17 years, and Bybee had heard numerous stories about the presence of fireflies in Utah.

“It turns out that people have known about fireflies in the state of Utah for a long time, over 60 years,” Bybee said. “We started to realize that people knew where the fireflies were better than we did.”

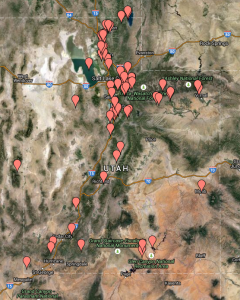

Bybee and Bills initially created the project together, and Bills has been managing the website. The website has so far been a success with more than 50 pins dropped on the community map to show where the fireflies are being seen.

It is clear from the map that the fireflies are primarily located along the Uinta mountain range.

“They kind of go right along the mountain range,” Bybee said. “They’re actually associated with wetlands down the mountain range, and you can see they’re also at the foot of the Uintas here out in the eastern part of the state. And then there are some other random sightings; there have been more and more popping up.”

Beginning last year, Bybee and Bills sent postcards to national parks where they would be posted and handed out to guests.

“This project gives the community the realization that science is an ongoing project, and it gets them excited,” Bills said. “My objectives are to get people outdoors and get people interested.”

Bybee’s objectives differ.

“We just want to get a distribution map, to publish some of our results about where we’re seeing them and then the different species in the state,” he said. “The ultimate goal for us, though, is to do some sort of population genetic study where we use DNA to sort out which populations are extinct, how populations are interacting and all that kind of stuff.”

The Utah research is really a side project to Bybee’s work on phylogenetic trees for the fireflies. With approximately 2,000 firefly species in the world, his lab has traveled to collect fireflies globally from Vietnam, Costa Rica, Peru, Ecuador, India and several countries in Africa.

Yelena Pacheco had been studying dragonflies for a year and working in the lab as an undergrad when Bybee contacted her to continue in the lab for firefly research. In summer 2014, she went to Rwanda for two weeks with Bybee and others to research.

“We’d go out at eight o’clock and collect all day long till 12 or one in the morning,” Pacheco said. “There was jungle environment and the other side of the country had savannah, ‘Lion King’ type. So we got to see different varieties of insects, which was very cool.”

The jungle proved to be more abundant with fireflies than did the savannah.

“We found the most in the jungle,” Pacheco said. “The sheer magnitude was really amazing. We went out and collected hundreds in an hour. You could fill your net up with 20 at a time.”

Gavin Martin worked in the lab as an undergraduate for 2.5 years. A recent BYU graduate, he now works as a lab technician for Bybee and is pursuing his Ph.D this fall at BYU.

Martin has been to Peru, Costa Rica and Australia for firefly research in the past but has also collected specimens in Utah. Next summer he will be validating the firefly submissions on the website by personally going to the areas.

He gave clear advice to Utahns hoping to see fireflies.

“You need to wait,” Martin said. “On all three locations we went to we almost gave up, and then as we were about to leave they came out. You’ll see one or two flashing right at sunset, and when it’s completely dark you can see 50 to 100 at a time.”

Bybee advised to wait until very dark before giving up. He said to find a marshy environment with tall grass and look low, toward the ground.

“I think one of the biggest reasons people haven’t seen them is that they’re found in mosquito-infested areas, at 9:30 p.m. when nobody is going to be there,” Bybee said.

Bills had a hard time finding fireflies herself.

“I’ve tried to collect from Moab to Bear Lake,” she said. “I would stare into the darkness for hours and hours and would see nothing. But then locals were thrilled to take me. It took person-to-person contact for me to see them.”

Fireflies tend to stay in secluded pockets that are hard to find in the dark. With the locals to lead her to the pockets, Bills finally saw the fireflies.

“They are super magical,” she said. “It’s like finding fairies. And there are a million different things to discover and learn.”

Reflecting on his experience on the lake’s edge in Rwanda, Bybee said, “I was terrified. But it was all for science, right?”